William Fulke: The Enemies of the Church of England

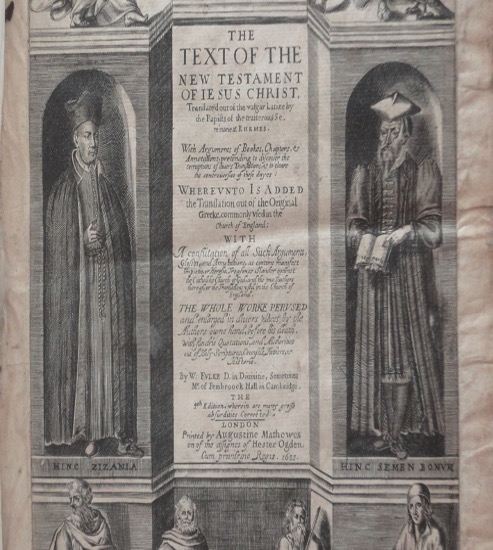

The earliest Bible which Feild owned was The Text of the New Testament of Jesus Christ (London: Augustine Matthewes and Hester Ogden, 1633) translated by William Fulke (1536-1589). As a translator, Fulke emphasized the importance of the English translation of the Scriptures in preserving the Church of England’s heritage. He was known as a “theological controversialist, exposing the errors of the Roman Catholic doctrine and defending the Church of England against theological attacks from English Catholic polemicists” (Bauckham 2). By the 1570s, Fulke was a popular Puritan preacher in London and a strong advocate for the Presbyterian movement within the Church of England. However, by the early 1580s, Fulke had abandoned his puritanical ways, choosing to support the official doctrine of England’s church.

With the assistance of noble patrons, Fulke dedicated his time to “answering all works of controversy written by English papists since 1558” (3) and published a number of texts in response to Roman Catholic attacks on the Church of England. In The Text of the New Testament, Fulke questioned the validity of the “Rhemish bible,” an English translation of the Latin version of the New Testament, completed in 1582 by Roman Catholics attending the Catholic College of Reims in England. Fulke tried to protect the English Bible from the “insolency of the Adversaries” (i) of the Church of England and Queen Elizabeth. Fulke never identified those enemies of England, but he indicated that he was writing against the Roman Catholic Church and English papists. While the Rhemish translators did allow people who spoke only English to read the New Testament, they included notes that praised the pope and argued that England should rejoin the Roman Catholic Church. To Fulke, this was treasonous behaviour because it threatened the political and religious authority of the English monarchy. His belief in the sanctity of a proper English translation of the Scriptures demonstrated how his fervour for the Church of England and the monarchy was deeply interconnected.

Additionally, Fulke’s desire for an English translation of the New Testament related to his aspiration for Christianity to return to the initial doctrines of the church. According to Fulke, the Old Testament was “first written in the mother tongue of the Jewes, and the New Testament in the Greek tongue, which was the mother tongue to a great part of the world” (ii). Fulke refuted the Roman Catholic assumption that Latin was the original language of the Scriptures, since it had undergone various translations throughout its history. The historical precedent of the Scriptures relates to Fulke’s own view on Bible translations. Accordingly, he wanted “everyone that readeth or heareth them, ought more diligently to studie” (ii) these texts. Fulke asserted that the Roman Catholic Church should not have control over the Scriptures; instead, everyone should be allowed to study them freely in their own native tongue in order to understand how to perform their religious responsibilities.

The presence of Fulke’s work in Feild’s book collection demonstrates how the Anglican bishop dedicated a section of his library to texts dealing with religious controversies. In this case, Fulke’s stance on the Roman Catholic Church may have resonated with field, as he owned several other texts that criticized papal practices. Likewise, both theologians believed that the Church of England was under attack by external and internal enemies. For Feild, the English government, namely Parliament, was trying to exert its influence over the Church of England to control the clergy. Feild wanted the church to return to its roots to build a foundation of independence from secular control.