Reaction to the French Revolution

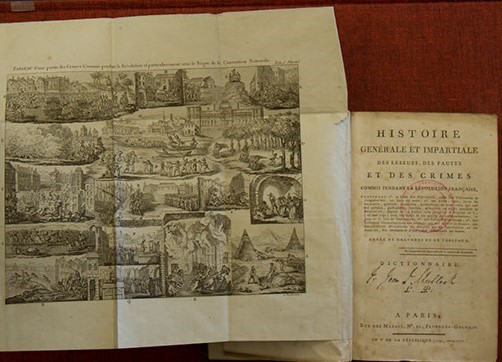

For all its glare, the Enlightenment also had its shadows, and if the French Revolution let shine the promise of modernity, it also revealed its darker perils. Following the royal family’s ill-advised and failed escape in June 1791, public opinion quickly radicalized against the crown and all hopes of a possible compromise between factions, that is, a constitutional monarchy, were lost. Louis XVI was eventually guillotined on January 21, 1793, and the new republic was straightaway forced to declare war on Britain, Spain, and Holland. Faced with this external threat, it turned its eyes to internal “traitors” capable of undermining its war efforts. Elected republican leaders, or the Convention, ordered the immediate and brutal suppression of any pockets of resistance found in the country, including the western region of the Vendée, where repression was decreed to be sans merci (merciless). When on June 10, 1794, the Revolutionary Tribunal instituted by the Convention adopted the Law of 22 Prairial, which effectively reduced trials to a mere formality, the brutality intensified into the Grande Terreur. The Revolution now turned on its own children: Georges Danton, Jacques Hébert, Maximilien Robespierre, the Girondins—all were slaughtered and across France a reign of arbitrary, inexorable terror was imposed. The sheer violence of these executions and the systematic manner in which they were conducted are a reminder that they were not only fuelled by military goals but also by ideological convictions. Earlier hopes began to fade as concerns arose: What if dogmatic religion had been replaced by a scientism just as intransigent? What if the triumph of reason brought with it the defeat of institutions that continued to be of value for society and individuals alike? Reactionary thought is precisely what looks to resist the steamrolling impetus of modernity and examine what is being lost in its wake. Inherently conservative and critical, it has produced some of the most trenchant, compelling prose ever written in French.

This is particularly the case of Joseph de Maistre (1753–1821), whose works Mullock ordered from Migne’s Atelier Catholique. With a certain sense of detached irony, he observed that the course of events during the French Revolution consistently eluded its authors. From beginning to end, it had been neither controlled nor guided by anyone involved. This stood as a lesson for human beings: reason is not vested with a creative power, the capacity to create society. Not only did this confirm that they were first and foremost creatures, it also reminded them that they were not pure essence hovering above earth and land. They did not produce the community; rather, they were its product. To this extent, the promise of temporal salvation offered by the French Revolution was fallacious and misleading, the re-enactment of the original sin, which was a sin of pride.