Erasmus and Classical Studies

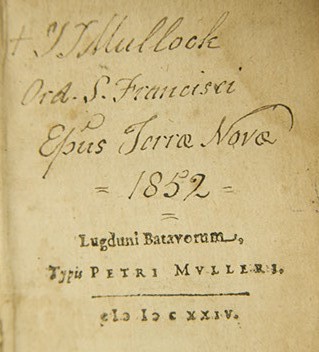

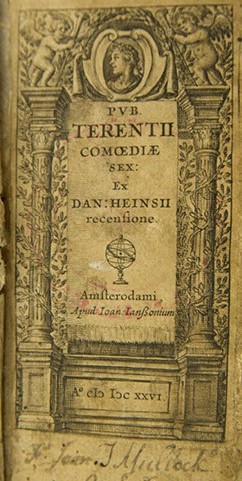

Apart from the copies of the Paraphrases and Chrysostom's works which (even for nineteenth-century Catholics) could have been regarded as useful tools for biblical studies, Bishop Mullock also obtained a more controversial collection of Erasmus's works bound together with the classical playwright Terence's comedies. Mullock signed this collegiate volume on the title page as a student on the Continent and later above the colophon as bishop of St. John's in 1852. The miniature edition, a format that became popular not only for Bibles but also for school texts from the seventeenth century onwards, contains a group of educational titles: an incomplete copy of Terence's comedies (Pvb. Terentii comediae sex) edited by the famous classical scholar and theologian of the Dutch Reformed church Daniel Heinsius; and Erasmus's Colloquia familiaria, Encomium Moriae, and De ratione studii. Along with Terence's comedies, Erasmus's Colloquia (Colloquies) and Encomium (Praise of Folly) were commonly used in early modern schools for Latin language practice, while Erasmus's educational treatise, De ratione (On the method of education), offered an introduction to the method of study advocated by humanist schoolmasters.

The copy in the Mullock collection is in quarto, bound in calfskin with gold inlay. Gold lettering appears on the spine, which has five raised bands, the bottom panel of which reads: “AMST. 1713.” The scuffed leather on the binding suggests that the volume was not just for show. Stronger evidence for this appears at the bottom of page 95 where a translation of the Latin verse on the page above (Carminum Lib. I. XXXVIII, “Ad Puerum”) has been pencilled in:

Although Erasmus's Colloquia, a collection of witty dialogues, quickly became a bestseller and was incorporated in the curriculum of sixteenth-century schools, its satirical tone and criticism of external religious practices soon invited censure. It was banned by the Tridentine papal indexes (1559, 1564), a verdict sustained by the extended list issued by Pope Clement VIII in 1596. It remained prohibited until the end of the nineteenth century. In The History of Heresies, Alphonsus de Liguori reaffirms its unsuitability as a school text, claiming that it contained “many things that lead the ignorant to impiety” (292). In fact, most of the common objections to Erasmus were derived from the sardonic dialogues of the Colloquia, as Liguori's list, quoted from Erasmus's ardent opponent, the Italian Albert Pico, Prince of Capri, attests. According to Pico, Erasmus “called the Invocation of the Blessed Virgin and the Saints idolatry; condemned Monasteries, and ridiculed the Religious, calling them actors and cheats, condemned their vows and rules; was opposed to the Celibacy of the Clergy, and turned into mockery Papal Indulgences, relics of Saints, feasts and fasts, auricular Confession; asserts that by Faith alone man is justified, and even throws a doubt on the authority of the Scripture and Councils” (292).

Encomium, Erasmus's most well-known—indeed notorious—work, was condemned along with Colloquia for its irreverent jibes. In his own defence, Erasmus claimed that Encomium outlined the same ideas of Christian life he described in his Enchiridion (The education of a Christian prince) but in the form of a joke. In Encomium, however, Folly's initial amusement at the unreasonableness of humankind quickly turns into a biting ridicule of the victims of folly found in every segment of society, including the religious orders and the clergy. Although after its first publication (1519), Encomium was widely celebrated by, among others, the English humanist Thomas More (later a Catholic martyr) and Erasmus's patron Pope Leo X, by the end of the sixteenth century it was permitted to be included in the collected works of Erasmus only in Protestant publications in the Netherlands, England, and Switzerland. It is not surprising, therefore, that Mullock's copies of the complete Colloquia and Encomium originated from Dutch printing houses.

Notwithstanding the official Catholic reservations, Mullock's book-collecting habits suggest that he was closer to the position represented by Erasmus's nineteenth-century biographer, Charles Butler. A graduate of the English College in Douai in France, Butler voiced, in his Life of Erasmus (1825), a moderate Catholic approach that transcended the unrelenting scrutiny of papal indexes: “All lovers of learning must ever wish to find Erasmus in the right; and, when he is not quite in the right, to find him very excusable” (153–54).