Desiderius Erasmus's Biblical Commentaries

The oldest surviving books in the Mullock collection are all associated with the Dutch scholar and theologian Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536), the leading Christian humanist of early sixteenth-century Europe. Although a Catholic reformer who remained faithful to the church during the Reformation, Erasmus was often attacked in his lifetime for his overt criticism of the practices of the church, his adversaries even accusing him of preparing the way for the Reformation and “laying the egg that Luther hatched.” His mixed reputation among Catholics (and Protestants) is well illustrated by the fact that, following the Counter-Reformational Council of Trent, Pope Paul IV placed Erasmus among the heretics on the Index of Prohibited Books in 1559. This general condemnation of Erasmus’s works was later mollified in the revised index of 1564, and further elaborated in the Antwerp Index expurgatorius (1571), which recommended the expurgation of his works, but, except for some titles, left them available to the Catholic public.

Erasmus’s precarious reception among Catholics persisted throughout the centuries. Although in The History of Heresies, Alphonsus de Liguori calls him, in Bishop Mullock’s translation, an “unsound Catholic, but not a heretic” (1. 292), Erasmus is still treated in the section on the heresies of the Protestant reformer Martin Luther. Nevertheless, Liguori confesses that Erasmus was highly esteemed by several popes. The nineteenth-century Catholic interpretations of Erasmus, still moulded by the categories of Reformation and Counter-Reformation, reflected this divided opinion: on the one hand Erasmus’s theology and criticism were seen as threatening to the dogmatic tradition and Catholic institutions; on the other hand, Erasmus was regarded as a reformer of the church and of religious life (despite his occasional doctrinal misconceptions). In light of this view, it is all the more interesting that Mullock’s Erasmian collection, a remarkable example of early print history, constitutes officially less sound and in some cases outright questionable works.

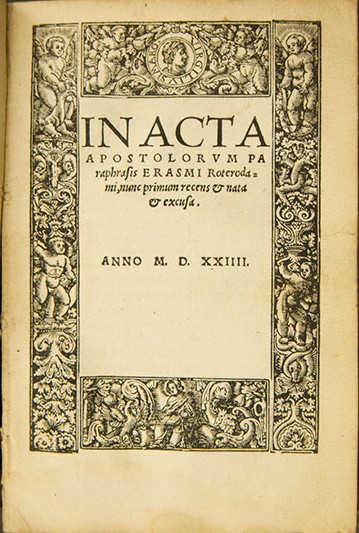

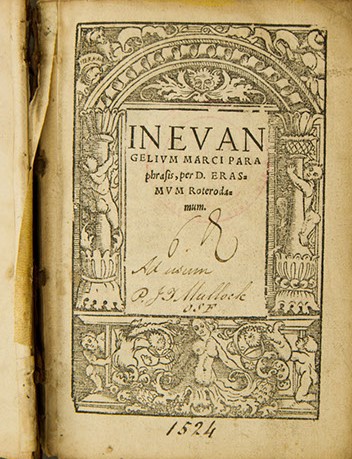

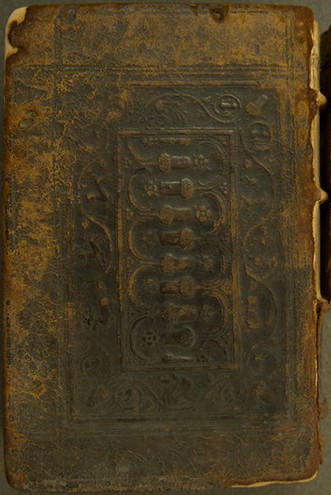

As a student, Mullock acquired a collegiate volume of Erasmus’s In Evagelicum Marci paraphrasis (Paraphrases on the Gospel of Mark) and In Acta Apostolorum paraphrasis (Paraphrases on the Acts of the Apostles), encased in its original sixteenth-century binding. Mullock’s copy of In Evagelicum Marci is an early (and rare) reprint, published by Johann Knoblouch in Strasbourg in the same year as the first edition was produced by Erasmus’s printer Johann Froben in Basel in 1524. Similarly, In Acta Apostolorum, another rare imprint, appeared anonymously shortly after its first publication in the print shop of Eucharius Cervicornus in Cologne in 1524. Erasmus intended the series of Paraphrasis as a layman’s guide to the Scriptures, an eloquent expression of his philosophia Christi and his pastoral mission formulated in his other works. Its first English translation exemplifies the rapid appropriation of Erasmus’s writings for political and religious ends in the sixteenth century. During Edward VI’s reign in 1547, the court-sponsored English Paraphrases was ordered to be placed in every parish church throughout England along with the official vernacular Bible and Book of Homilies, an epitome of the reformed doctrines of the Church of England. It may have been Mullock’s interest in the history of the English Reformation (which he articulated in the translator’s preface of The History of Heresies) that prompted him to acquire a copy of the Paraphrasis, an instrumental text for reformers in their vision of the religious transformation of England.

Mullock’s continued interest in Erasmus is attested by two copies of the early church father John Chrysostom’s works. As an ordained priest in Europe, Mullock purchased Chrysostom’s commentaries on the letters of Paul and a collection of homilies that formed part of Chrysostom’s collected works (Opera omnia). They were published within a few years of their first appearance by the Basel printer Johann Herwagen in 1536 and 1539, respectively. Chrysostom exerted considerable influence on Erasmus’s theological development, especially with respect to the issues of will, justification, and grace (hotly debated by Catholics and Protestants) that shaped rather controversially Erasmus’s paraphrases of Paul’s letters to the Romans. Although Herwagen credits Erasmus as the editor of Chrysostom’s works, most of the commentaries in Mullock’s copies were in fact composed by Protestant writers, primarily by the German reformer Wolfgang Mauslein (or Musculus), whose devout hymns are still sung in reformed churches and elsewhere, most notably in the adaptation of Johann Sebastian Bach’s cantatas.