Johannes Buxtorf and Christian Hebraism

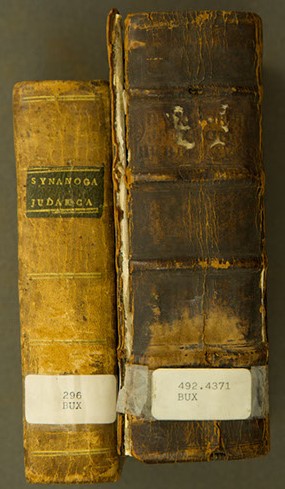

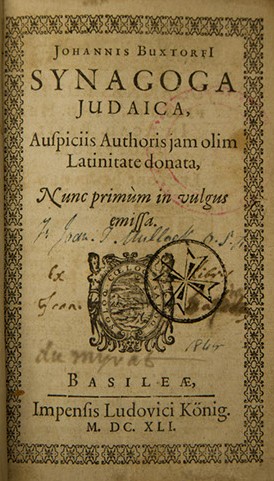

As well as the wide selection of Bibles and language aids in the Mullock collection, there were also a number of Hebrew reference works, some of which date from the seventeenth century. Of particular interest are two volumes by Johannes Buxtorf the elder (1564–1629), Lexicon Hebraicum et Chaldaicum (1646 [1607]), a Hebrew and Chaldean lexicon, and Synagoga Judaica (1641 [1603, in German under the title Juden Schule]), which contains detailed descriptions about Jewish religious beliefs, prayers, ceremonies, and religious practices (not about the synagogue as such). Buxtorf was an early Christian Hebraist, that is, someone who, as a Christian, had an interest in Jews and Jewish literature. In many ways, Buxtorf was responsible for establishing Hebraic and Jewish studies as a recognized discipline in many universities and schools. It made Jewish learning possible without assistance from the Jews who were, at this time, publicly shunned and ostracized. In fact, in 1619 Buxtorf was heavily fined (his fine was higher than his yearly salary as a university professor) and reprimanded for attending the circumcision of the son of one of his printer friends, Abraham Braunschweig. Many of Buxtorf’s books were used well into the nineteenth century after the emergence of biblical studies as an academic discipline.

The Lexicon Hebraicum et Chaldaicum is a valuable tool for understanding the origin and development of the Hebrew language. Buxtorf used many rabbinic sources in determining the meaning of the various Hebraic roots and explicated their meanings further when they concerned Christian theological concepts. The Lexicon proved invaluable for scholars, and many of the Christian Hebraists of the seventeenth century such as Joseph Justus Scaliger and John Lightfoot recommended it. It enjoyed an excellent reputation well into the nineteenth century and remained a standard in the field until it was finally superseded by Wilhelm Gesenius and others who promoted the use of cognate Semitic languages to deal with linguistic problems.

Of special interest, too, is Buxtorf’s Synagoga Judaica, which is the first extended account of Jewish religious beliefs and practices written by a non-Jew for a Christian audience. In it Buxtorf gives a detailed account of Jewish rituals relating to birth, circumcision, marriage, death, and feasts like Succoth and Passover. While Buxtorf’s explicit intention was to dissuade Christians from adopting the Jewish faith, his meticulous scholarship into the theological significance of almost every Jewish practice indicates that, beneath a polemical exterior, there lies a scholar with deep respect for Judaism. It became the standard work on Judaism for well over 100 years and shaped Christian ethnographic research on the Jews well into the nineteenth century. His underlying theology of Judaism was common to Protestants and Catholics alike.

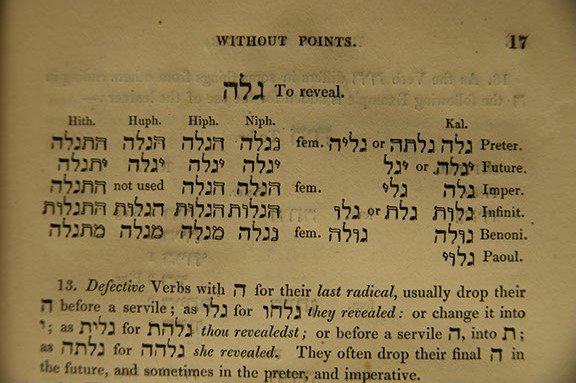

Buxtorf entered into a controversy with Louis Cappel over the accuracy of the Hebrew vowel points. Buxtorf argued that the vowels points ensured the transmission and correct readings and vocalizations of the Hebrew Bible. If the vowel points were added later, as Cappel and others suggested, the Bible (or at least the vocalization of the words) was the work of a human intellect rather than a divine one, and thus the authority of the Bible as the Word of God would potentially be undermined. This is a position that no Protestant could take lightly. In conclusion, it seems that Mullock possessed and studied Bibles in their original languages, that he used a variety of lexical and philological aids to understand the original biblical languages, and that he was interested not only in ethnographical research on the Jews but also in the controversy surrounding the use of Hebrew vowel points. This was a controversy that, in some respects, struck at the core of what it meant to be a Protestant and what it meant to be a Catholic, even in nineteenth-century Newfoundland.