Eighteenth-Century British Historians

Works from two of the finest historians of the eighteenth century—William Robertson (1721–93) and Edward Gibbon (1737–94)—are extant in the Mullock collection.

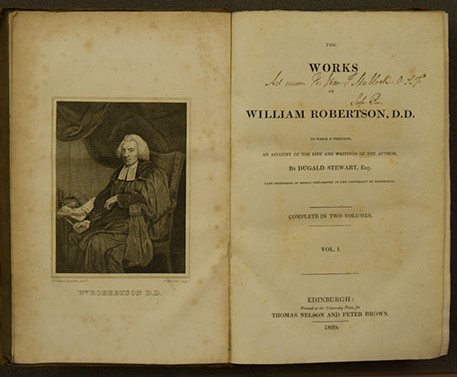

Bishop Mullock had Robertson’s History of the Reign of the Emperor Charles V (2nd ed., 4 vols. [London, 1772], as well as a 1777 Dublin edition of vol. 1), The History of America (London, 1783), and the first of two volumes of an 1829 Edinburgh reprint of The Works of William Robertson, D.D., edited by Dugald Stewart (printed at the university press by Thomas Nelson and Peter Brown). Robertson was best known for The History of Scotland during the Reigns of Queen Mary and King James VI, first published in 1759. Given the turbulent reign of Mary Queen of Scots (who ended up on a chopping block) and her son (who eventually succeeded Elizabeth I as James I of England), Robertson’s History proved a great success, going through some thirteen editions within his lifetime. Robertson became principal of the University of Edinburgh and moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. One of Robertson’s most animated fans was the great actor and theatre impresario David Garrick. Garrick wrote an enthusiastic letter to the publisher declaring that Robertson’s History of Scotland had made such an impact on him that he was compelled to read it aloud to his wife and guest over two sittings. The frontispiece, based on a portrait of Robertson by Sir Joshua Reynolds, was engraved by E. Mitchell.

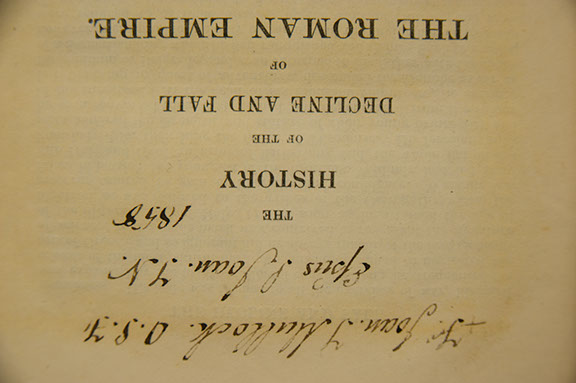

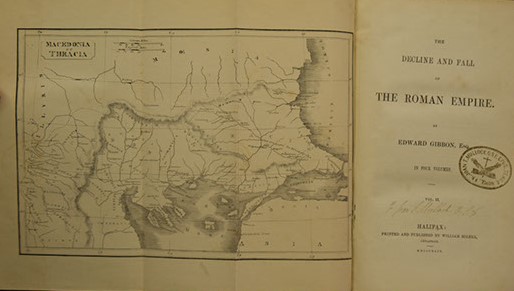

The other significant historical masterpiece in the Mullock collection is his four-volume set of Edward Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, originally published between 1776 and 1789. Mullock opted for a cloth-bound edition from 1845 printed and published by William Milner of Cheapside, Halifax, Yorkshire, who had a reputation for producing inexpensive books.

Mullock’s customary signature and stamp appear on the title page. At the head of chapter 53 appears a carefully inscribed signature—“† Fr Joan. T. Mullock. O.S.F. | Epus S. Joan. T.N. | 1858.” The short form of “Joan.” for Joannis, the Latin for John, applies equally to his first name and the name of his town. T.N. for Terra Nova survives in businesses in Newfoundland to this day

Gibbon attended Magdalen College Oxford at the age of fifteen and converted to Roman Catholicism in the following year. His father sent him off to Lausanne, Switzerland, where a Calvinist pastor persuaded him to return to Protestantism. While religion became more an object of study than a matter of faith for Gibbon, Rome nonetheless continued to hold him in her spell.

On his first and only visit to Rome during an extended Grand Tour, Gibbon experienced an epiphany. As he recorded in his Autobiography, it was on October 15, 1764, “as [he] sat musing amidst the ruins of the Capitol, while the barefooted friars were singing vespers in the Temple of Jupiter, that the idea of writing the decline and fall of the city first started to [his] mind.” A dozen years later the first impression of the first volume of Decline and Fall sold out within a matter of days. At first glance Gibbon’s central thesis may not seem the stuff of bestsellers—that “the propagation of the Gospel, and the triumph of the Church are inseparably connected with the decline of the Roman monarchy.”

The fifteenth and sixteenth chapters, which examined the early flourishing of Christianity, created considerable controversy. Church of England clergymen felt that Gibbon’s history was too glib, that Gibbon was more inclined toward Roman paganism than Christian devotion. His dry, occasionally cynical tone, but solid, scholarly approach fit in well with the ideals of the Enlightenment that had taken root in Scotland and France. Robertson and two other powerhouses of the Scottish Enlightenment, David Hume and Adam Ferguson, applauded Gibbon’s scholarship. Ferguson furnished an introduction to Decline and Fall in 1783. Hume, who died the year the first volume came out, warned its author of the clamour his work would create in England. Gibbon thought that the concept of the afterlife helped promote the spread of Christianity: “When the promise of eternal happiness was proposed to mankind on condition of adopting the faith and of observing the precepts of the Gospel, it is no wonder that so advantageous an offer should have been accepted by great numbers of every religion, of every rank and of every province in the Roman Empire.” Using the language of commerce (“so advantageous an offer”), Gibbon suggested that Christianity thrived because its backers really knew how to sell the product. No small wonder pious readers were upset. Reactions to Gibbon varied considerably. One of the most memorable reader responses came from the Duke of Gloucester, brother of George III, who on being presented with the second volume, said, “Another damned thick, square book! Always scribble, scribble, scribble, Eh! Mr. Gibbon?” A more serious response came from the Vatican, which placed this historical landmark on the Index of Prohibited Books in 1783.

Gibbon’s Decline and Fall was de rigueur for anyone interested in history. For Mullock, Gibbon’s history would have come in handy for background to his lecture “Rome, Past and Present” which he delivered in St. Dunstan’s Cathedral, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, on Thursday, August 16, 1860. For a Roman Catholic bishop whose scholarly pursuits included a translation of Alphonsus de Liguori’s The History of Heresies, Mullock may not have been overly shocked by Gibbon’s Decline and Fall. He had another set of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall, published in Boston in 1860, lacking the first of six volumes.