Feild and Antiquarianism: William Camden and James Henry Boswell

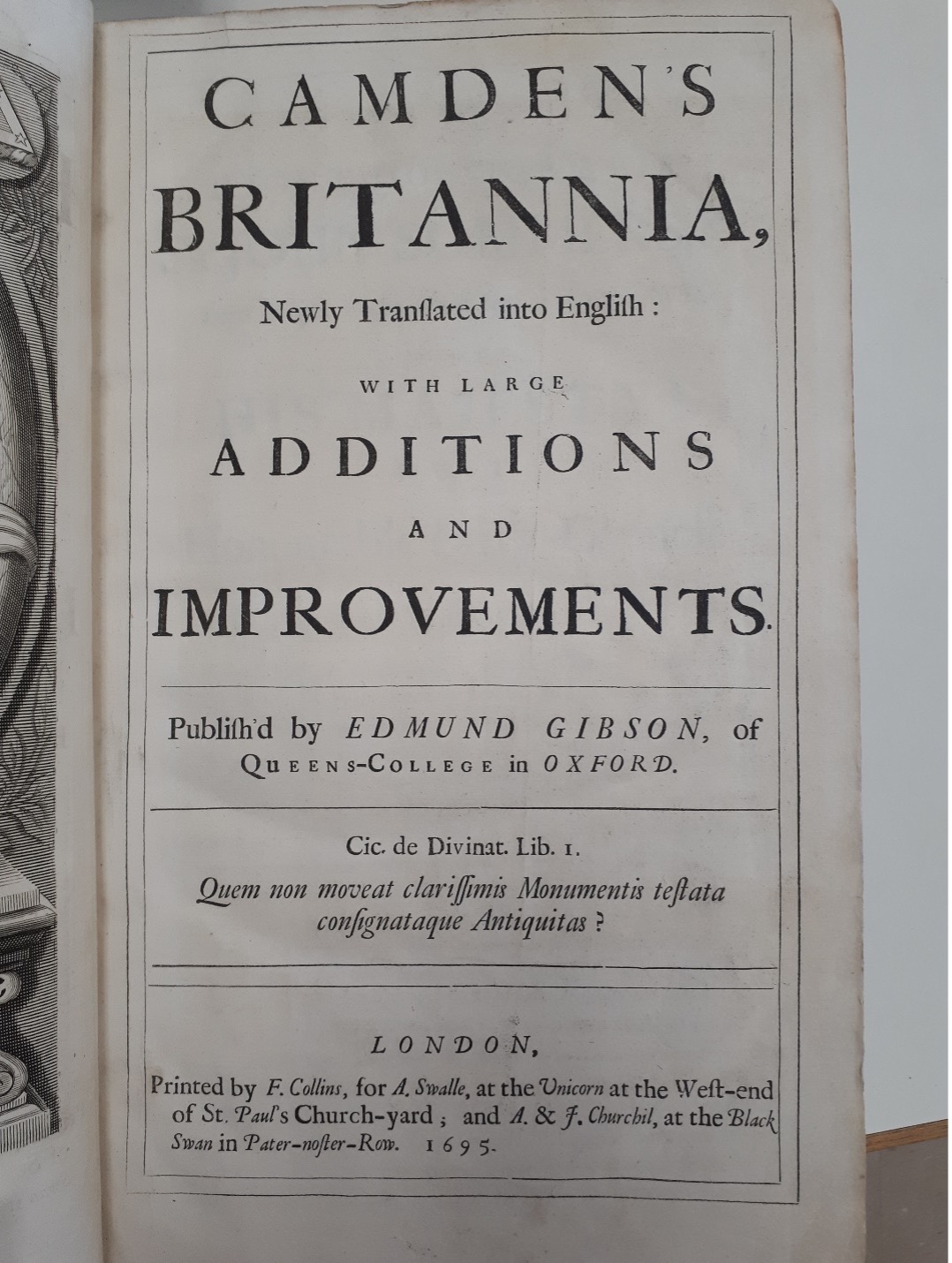

As a book collector and follower of the Cambridge Movement, Feild was interested in antiquarian studies that examined England’s geographic and architectural past. The Cambridge Camden Society argued that the clergy needed to return to Gothic architecture as a means to protect the Church of England’s traditional identity and to propagate medieval Christian practices. Feild wished to recreate what he and other Cambridge Movement followers considered the golden age of Christianity by building Gothic churches across Newfoundland to reestablish churches as the main places of worship in response to Evangelicals’ and Wesleyans’ use of secular buildings for acts of devotion. Field’s ownership of William Camden’s Camden’s Britannia, Newly Translated into English: With Large Additions and Improvements (London: 1695), published by the bishop and antiquarian Edmund Gibson (1669-1748), and of James Henry Boswell’s Complete Historical Description of Picturesque Views and Representations of the Antiquities of England and Wales (London: Alex Hogg, 1786) indicates his intent to collect books dedicated to interpreting England’s history.

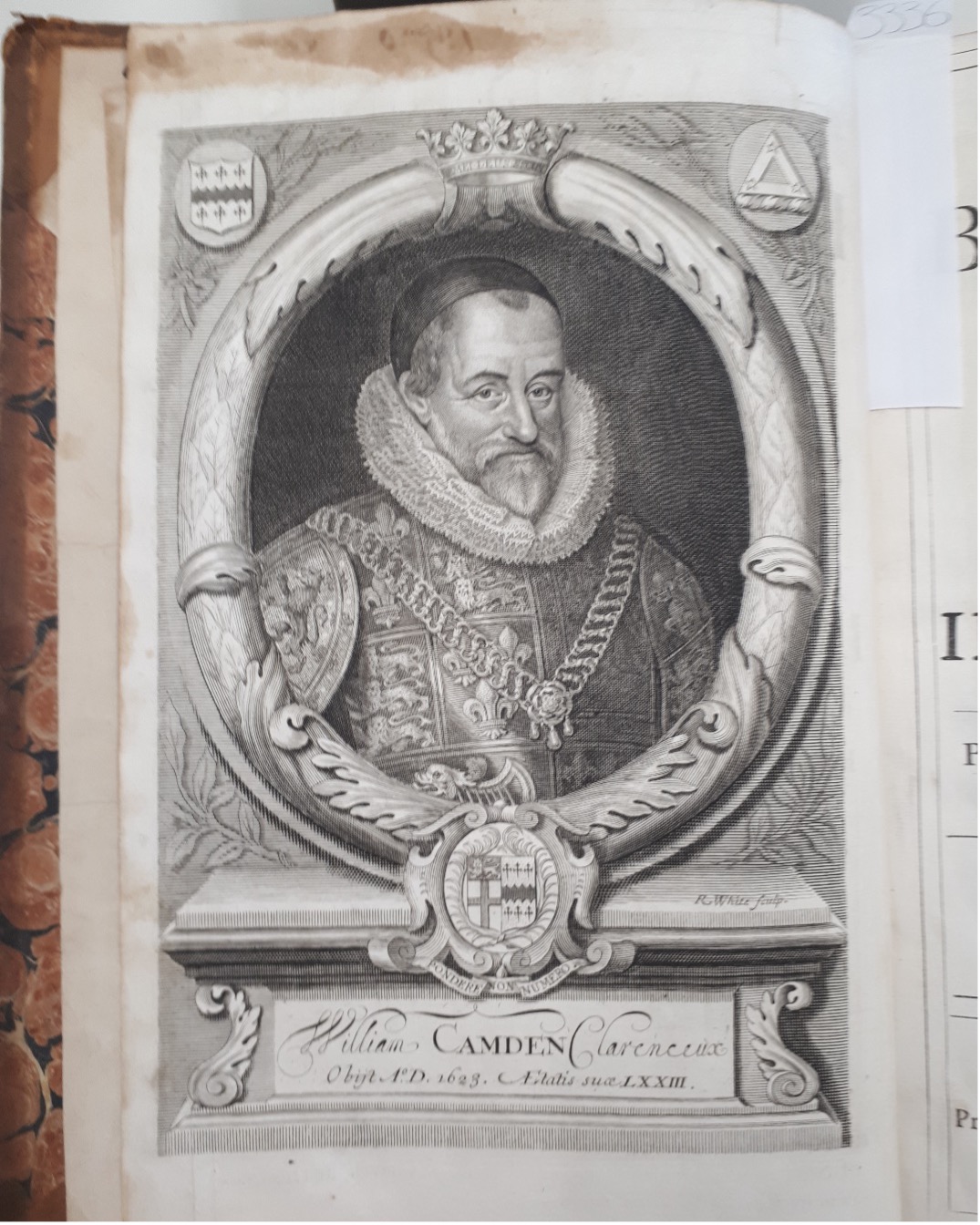

William Camden (1551-1623) was a famous English antiquarian who focused his writings on how Rome’s invasion of England helped to shape the country’s administration, architecture, and language. Camden’s goal was to “acquaint the World with the ancient state of Britain, that is, to restore Britain to Antiquity and Antiquity to Britain; to renew what was old, illustrate what was obscure, and settle what was doubtful” (i). The Britannia changed how people viewed English history and shaped how Europe considered English society as a continuation of Roman ideals (Herendeen 2). Gibson, its seventeenth-century editor, argued that Camden’s work corrected the errors that sixteenth-century non-English historians incorrectly reported about England. Before Camden published his work, only foreign historians, namely from the continent, produced extensive histories that connected Britain to its Roman ancestry. However, Gibson noted that “Britain was another world to them [and they] were forc’d to clap up things in general terms” (ii). These historians failed to account for England’s historical particularities, such as the origin of its place names, and opted to describe events without any explanation.

As Wyman H. Herendeen argues, the “Britannia had an enormous and lasting impact on multidisciplinary historical writing, and was also of the highest importance as a cultural icon affected the national image” (5). Camden used country records, architectural designs, local folklore, and oral history to explore why Britain’s villages, towns, and counties developed in certain ways. He found that the extant records were difficult to interpret because they came from three ages of conquest, in which the conquerors used different languages to document events. Camden further extrapolated from past records what cultural and political course present-day Britain should follow. Gibson added to Camden’s work by compiling various clergies’, bishops’, and scholars’ antiquarian research on England. In his preface, Gibson praised Camden’s work because the “characters of Men, and the actions of Ages … do both stand unalterable. Whereas the condition of places is in a sort of continual motion, always (like the Sea) ebbing and flowing” (i). To Gibson and his fellow researchers, Camden’s Britannia exemplified the need for antiquarian studies, and they wanted to ensure that the text’s popularity continued into later centuries in order to maintain this historical research.

James Henry Boswell (1740-1795) also provided an important overview of England’s past. Boswell was a Scottish-born writer and lawyer with family connections to the Earls of Mar on his mother’s side (Turnbull 1-3). As a child, Boswell’s mother and father raised him as a Calvinist; a strict Anglican faith Calvinism taught its followers that God had already ordained who would go to heaven or hell. Boswell, who suffered from bouts of depression as a young man, grew to resent Calvinism and later adopted a more carefree life. He initially did not want to follow in his father’s footsteps of becoming a lawyer, but he eventually capitulated to his family’s demands. Yet, Boswell also turned to writing during this time as an outlet for his frustrations with life. He also enjoyed several walking tours across Europe (2), which inspired him to write about landscapes, architecture, and cultures, in addition to his more well-known works on Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), a famous English writer.

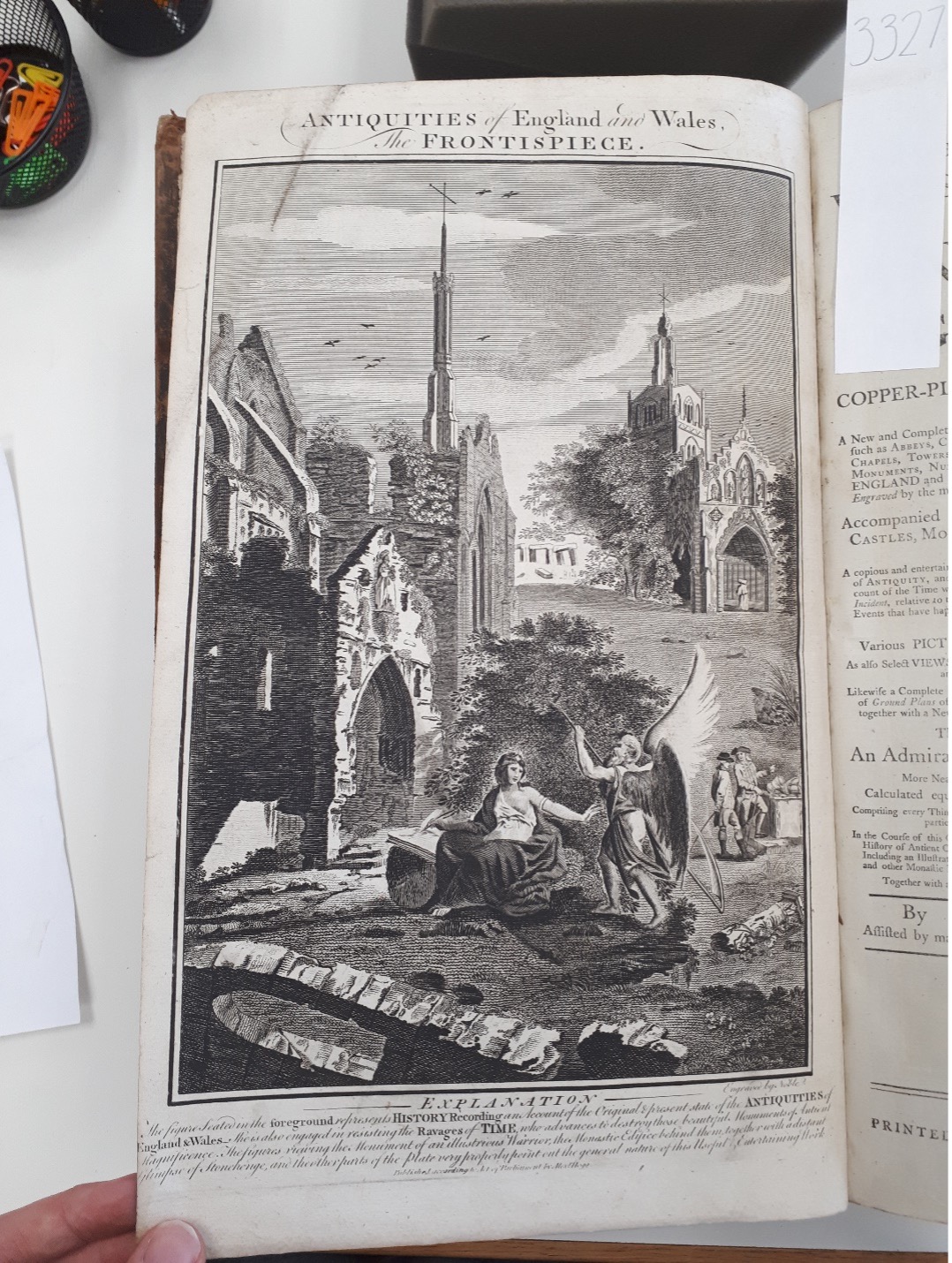

Boswell’s Complete Historical Description of Picturesque Views and Representations of the Antiquities of England and Wales lists different building styles and important places in England and Wales. Boswell has included several sections on Gothic architecture, listing a number of medieval churches. Alongside each example is a well-drawn illustration that acted both as a diagram and representation of the real building. Feild would have been interested in this book as an example of antiquarian research, especially since he was a part of the Cambridge Movement, which wanted to reestablish medieval architecture. Feild may have used some of Boswell’s examples as inspiration for the construction of Gothic churches in Newfoundland.

Feild’s inclusion of Camden’s and Boswell’s works in his collection demonstrates his intent to study England’s antiquarian past. These particular books link Feild’s collection to his desire to build Gothic churches on the island. Architecture was a major component of each of these books, especially the design of older churches and how earlier cultures inspired these styles of buildings. Namely, these texts, alongside Feild’s other books, indicate that the bishop believed strongly in upholding traditional practices.