Alexander von Humboldt's Cosmos and Natural Philosophy

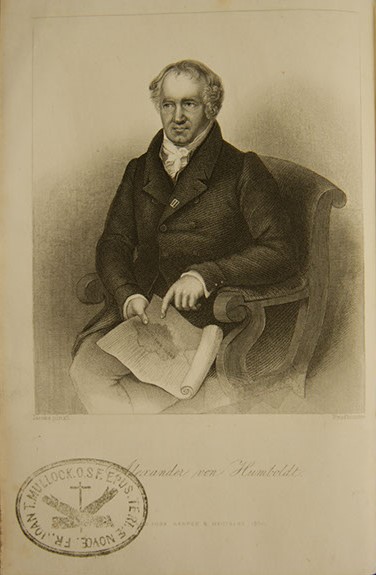

Among nineteenth-century literati, Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) possessed a considerable international reputation as one of the world’s greatest naturalists, geographers, and explorers. Humboldt arose to scientific and scholarly prominence early in life with works on botany and mineralogy. This gained him the recognition of other European luminaries, notably Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, and Louis-Antoine de Bougainville. Between 1799 and 1804, Humboldt travelled extensively through South America, Cuba, Mexico, and the United States. In the decade after his return to Europe, Humboldt published some 30 volumes that synthesized his notes, specimens, and measurements collected during his voyage into a cohesive account of the Americas. These volumes won Humboldt acclaim among reading publics as well as among scientists and scholars.

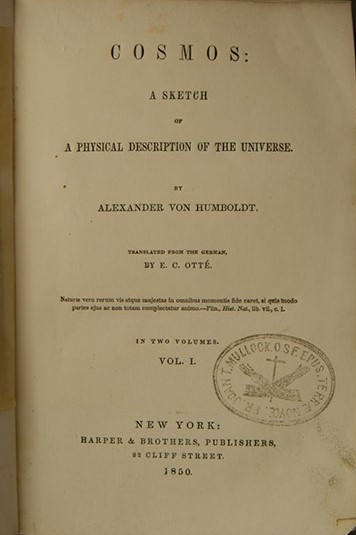

Humboldt’s most ambitious undertaking was the work Cosmos: A Sketch of the Physical Description of the Universe (1845–62) written toward the end of his life. The project was conceived as an assemblage of all the then-available knowledge of the earth and the heavens. To ensure that Cosmos reflected the most current science, Humboldt solicited information from scientists and experts around the world on the myriad of topics to be covered. Astronomy, paleontology, climatology, meteorology, geology, and botany, as well as poetic descriptions of nature and the history of the physical sciences, found a place in Cosmos. The essential insight was that cosmic order emerged entirely from local landscapes. Humboldt sought to show how meticulous observation, surveying and averaging over ever-greater geographies, would reveal the constant and unchanging laws of nature obscured by local differences and particularities.

Reading publics as well as other scientists appear to have found Humboldt’s ideas deeply compelling. The first volume of Cosmos was published in German in 1845. It was an immediate success, selling over 20,000 copies in just a few months. Its English translation sold more than 40,000 copies within four years. Indeed, the mania for Cosmos among English readers was so great that there was not just a single translation but three, one of which is in the Mullock collection, the translation by Elise C. Otté, the Danish linguist and historian, first published in Britain in 1848 and issued later in the United States.

Given the tremendous popularity of Humboldt’s Cosmos, there is little wonder that it was acquired by John Mullock. What is striking, however, is that Cosmos is an anomaly insofar as it seems to be one of very few scientific works in Mullock’s quite large collection of books. Notable for their absence are other widely read and influential scientific works. Absent is Newton’s Opticks (1704–18) which helped shape almost all eighteenth-century thought from natural philosophy to political economy. (Mullock may have acquired, but did not sign, one of Newton’s several works in theology and biblical exegesis.) Also not in the collection is Carlos Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (1735–68), which was canonical for all practitioners of natural history, including Humboldt. Nor is there a copy of Antoine Lavoisier’s Elementary Treatise on Chemistry (1789), which deeply influenced Humboldt for its startling redefinition of the chemical element and its introduction of a new system of chemical nomenclature. Indeed, if Mullock had been much interested in natural history, Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830–33), Robert Chambers’s Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844), or Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) would be more likely found in the collection. (Mullock may have collected one of Thomas H. Huxley’s many defenses of Darwin.)

If Mullock collected Cosmos for a reason other than for its popularity, then the reason might be this: In his lectures and book collection, Mullock shows a sustained concern with how Newfoundlanders, fish, and fishing are tied into larger global patterns of trade and migration. This arguably indicates a natural historical concern with showing how local regions, with their own distinctive character, are situated in larger global geological, geographic, and biological patterns. This approach to natural history was pioneered by Georges-Louise Leclerc (1707–88, later Comte de Buffon) in his Natural History, General and Particular (1749–88). There are two copies of this text among the books presumed to be collected by Mullock but not signed by him. As in Humboldt’s Cosmos, Buffon’s natural history emphasized how geological formation, the distribution of biological species over geographic space, and the morphology of species all could be explained by physical causes. It seems quite unlikely that Mullock espoused the physicalism of either Humboldt or Buffon, given the manifest metaphysical and theological emphasis of his book collection. Perhaps then what Mullock took from the few volumes of natural history he possessed was a Humboldtian impetus to carefully explore local particularities and then to situate them within larger geographic empires.