The 1861 Political Unrest

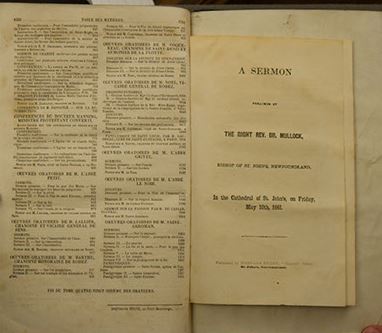

Mullock pasted some of his pastoral letters into the inside covers and flyleaves of Jacques-Paul Migne’s Collection intégrale et universelle des orateurs sacrés du premier et de second ordre, not because they related to the content of the book in any way but because it was large enough to hold the printed letters, ensuring their preservation. Pasted into volume 86 of Collection intégrale (published by J.-P. Migne in 1856) is the fifteen-page pamphlet A Sermon Preached by the Right Rev. Dr. Mullock, Bishop of St. John’s, Newfoundland, in the Cathedral of St. John’s, on Friday, May 10th 1861 that was prompted by the most controversial events in which Mullock had involved himself.

With the active support of the Roman Catholic church, the Liberal party had dominated the legislature since the beginning of representative government in 1832. The Tories saw an opportunity to form a government when a rift developed between Mullock and Premier John Kent. Governor Alexander Bannerman, who had his own problems with Kent, dismissed the Liberals and asked the Tory Hugh Hoyles to form a government. The Church of England bishop Edward Feild publicly supported the Tories; Mullock repaired his relationship with the Liberals and urged Roman Catholics to listen to their priests and vote Liberal. Since the Tories lacked a majority in the House of Assembly, an election became necessary. For Bannerman, whose actions were constitutionally improper, a Tory victory would vindicate him. Such an outcome would, the Liberals felt, steal power from them.

Against this backdrop, the 1861 election was sharply contested. Bannerman used the threat of violence to delay election in the District of Harbour Grace, which would have returned two Liberals. In nearby District of Harbour Main, four Roman Catholic Liberals competed for the two seats in the House of Assembly the district merited. Two of these candidates were supported by the priests; the other two were independent Roman Catholics. Some Liberals, both Protestant and Roman Catholics, disliked clerical interference in politics, although Mullock felt it was his duty to instruct Catholics how to vote. Accompanied by two priests, voters from Salmon Cove walked to Cat’s Cove to vote for the candidates favoured by the church, but were prevented from doing so by people of that community. Several men were wounded, and one, George Furey, was killed.

The pamphlet containing Mullock’s sermon on the subject of Furey’s killing was pasted into this volume. The publisher’s preface set out an account of the election and blamed the violence on the government and “the spirit of Orange ferocity.” On the surface Mullock’s sermon appealed for a cooling down of partisan anger. Mullock began by observing that, in Newfoundland, “Catholics and Protestants live together in the greatest harmony, and it is only in print we find anything … like disunion among them.” But the sermon was consistent with his earlier comments that raised the spectre of a Protestant war against the Catholics. Raising the example of Jews who asked Pilate to kill Jesus, Mullock blamed the (Protestant) instigators of dissension as much as those (Catholics) who killed Furey. The “vile press,” by which he meant the anti-Catholic newspaper editors, had been promoting murder, and Mullock condemned those who carried knives and revolvers. This was a veiled reference to the Orange threat he had been warning of for months. He also implored Furey’s friends not to take revenge but to wait for the court’s determination. Mullock said that subjects had a duty to obey the law, just as the authorities had a duty to punish crime. To do otherwise, he warned the governor and the judges, was to encourage further crime.

Fearing retribution from voters in his district, the returning officer in Harbour Main had signed documents declaring all four candidates elected, but the government denied any of the Liberals from Harbour Main their seats until an investigation could be conducted. When the House met, supporters of the “Priest’s Party’s” men who had been denied seats rioted. A standoff with the garrison escalated into the troops firing upon the crowd, which resulted in three fatalities and many injuries. The rioting stopped only after Mullock rang the cathedral bells, the rioters assembled to hear him, and he asked for peace. To his critics, Mullock had encouraged the violence and belatedly tried to tamp it down after the killings. The violence ended that day, but resumed over the next few days; Bannerman restored order by using troops. Mullock pasted an editorial on these events into volume 4 of Jean Bolland et al.’s Acta Sanctorum Maii collecta, digesta, illustrata (Venice, 1740). Much later the governor released the men of Cat’s Cove from prison, prompting Mullock to close the Cat’s Cove church and deny the people of that community any sacraments for one year. He also pasted a copy of his “interdiction” into volume 82 of Collection Intégrale published by J.-P. Migne in 1856.

After 1861 both Roman Catholic and Protestant clergymen lowered the level of their partisan rhetoric, ending the worst election-time violence of the nineteenth century. A process of sharing money and power among the denominations and the institution of the secret ballot ended open sectarian conflict. Mullock largely withdrew from politics for the remainder of his life. The events of that year election had diminished the political power of the Roman Catholic and Church of England bishops.