The Mullock Collection

The books amassed by Bishop John T. Mullock at different stages of his life in Ireland, Spain, Italy, and Newfoundland and throughout his travels in England, Continental Europe, and North America provided the foundation for the extensive collection presently housed in the Mullock Library. Although Mullock’s collection has been significantly augmented by successive generations of archbishops (most notably by Mullock’s biographer, Archbishop M. F. Howley), Mullock’s original bequest still constitutes the principal part of the current Mullock Library. The earliest description of the library’s holdings was provided by Mullock himself who, in his report to the government in 1859, related that he offered his own private collection of “over 2500 volumes as the nucleus of a Public Library,” emphasizing that “many of these books are rare and valuable.”[i]Intended both as a public and school library for Mullock’s educational establishment, St. Bonaventure’s College, the original Mullock Library was part of its founder’s vision of creating a cultural centre in St. John’s, serving not only the Roman Catholic clergy but also the community at large. As Mullock announced in his February 22, 1857, Pastoral Letter, he was intent on supplying “the most select works for the library, everything in fact that can promote education.”

Since Mullock habitually inscribed his acquisitions with his ownership marks, including a variety of signatures and Episcopal stamps, 278 titles in 1,279 volumes from the current collection can be securely attributed to him. The remaining titles in 1,766 volumes of unsigned books printed before his death can be assigned only tentatively to Mullock, although, in many cases, ownership can be attributed to him with reasonable certainty. In fact, the subject matter and general coverage of the unsigned books often closely correspond with copies signed by Mullock. A significant and unfortunate reduction of the founding collection occurred in the 1960s when, according to eyewitness accounts, a considerable number of “old books,” particularly in the history, geography, and the Newfoundland reference sections, were discarded to make space in the bookcases for new arrivals and for volumes considered at the time more up-to-date. In 1965, a large portion of Mullock’s collection of patristic literature and theological works, printed by the nineteenth-century bookseller and editor Jacques-Paul Migne, was donated to Memorial University’s Queen Elizabeth II Library. All 221 volumes of the Patrologia Latina series, 104 volumes of the Patrologia Graeca series, 28 volumes of the Theologiae series, a thirteen-volume newly edited set of the church father John Chrysostom’s works, and four volumes by the medieval theologian and philosopher Thomas Aquinas were transferred to the open stacks of the Queen Elizabeth II Library, where they are still available for use by the university public. The collection at the Mullock Library was catalogued in the 1970s according to the Dewey Decimal Classification system, but the accompanying card catalogue has regrettably gone missing. To fulfill Mullock’s initial intention to create a publicly accessible collection, a searchable electronic catalogue is now available on The Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Website.

Reflecting his multilingual skills, Mullock collected books in a broad range of languages, including English, French, Italian, Latin, Spanish, Greek, Danish, and German.

Languages

Signed Unsigned

Latin 427 522

French 416 179

English 170 809

Italian 154 221

Greek 105 0

Spanish 11 25

Danish 1 0

German 0 6

Irish 0 3

Portuguese 0 1

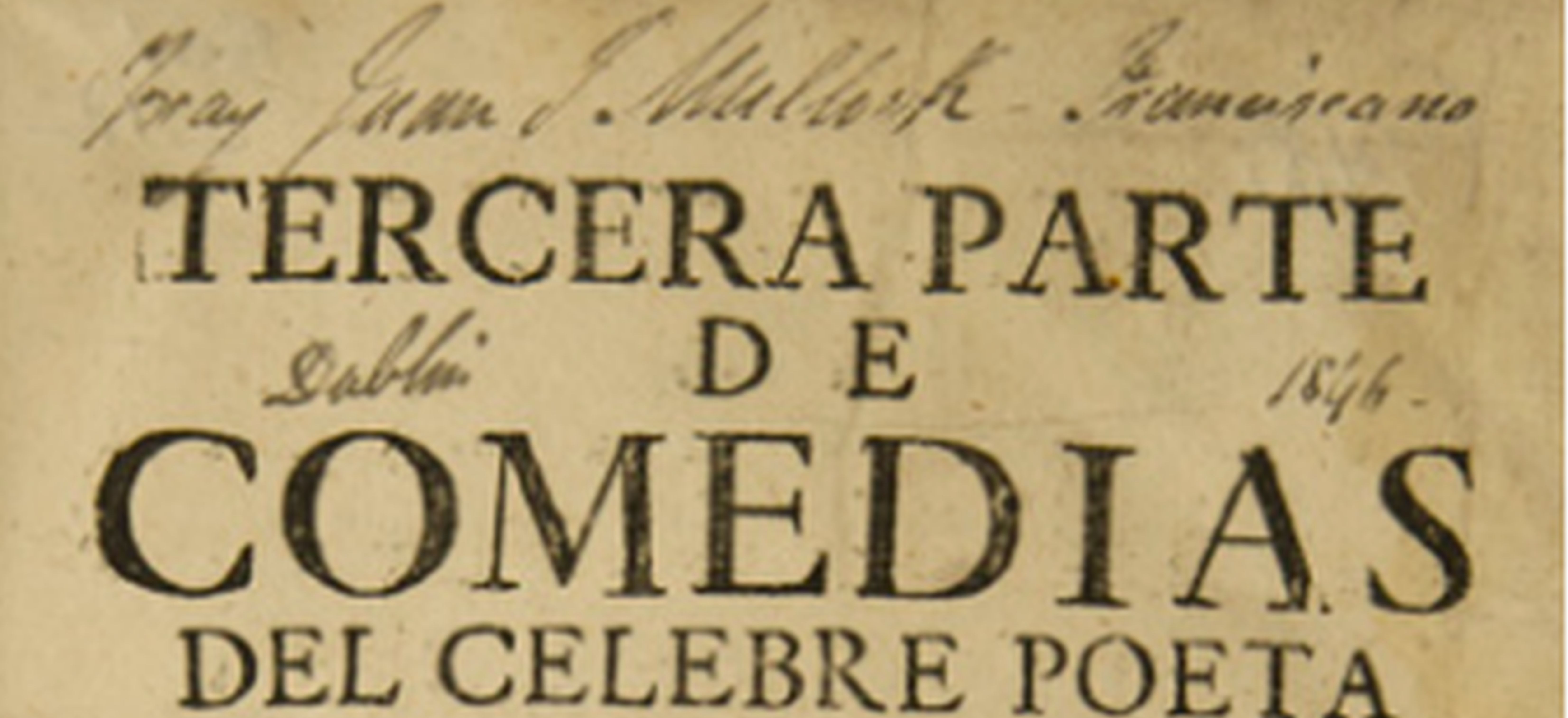

While the dominance of books in Latin, Mullock’s professional language, is to be expected for a priest and theologian, the sizeable and diverse French collection was less of a norm for an Irishman whose mother tongue was English. However, as Howley notes in his biography, Ecclesiastical History of Newfoundland, Volume Two (St. John’s, 2005), Mullock had gained some proficiency in French already in Ireland: “He acquired a knowledge of classics at the Academy of Mr. George O’Keefe, and a good grounding in French from a lady who gave him private lessons” (10). Similarly, Mullock quickly learned Spanish as a student in Seville and, as Howley remarks, “Not only did he in a short time become a fluent master of the noble Castilian language, and speak with correctness of idiom, and purity of accent, but he became a student of the Literature and Poetry of the country, as is testified by the extensive collection of Autores Espanoles (Spanish Authors) viz.: Cervantes, Quevedo, Ercilla, Meriano, Balmes, Ximenes, etc., which now adorn the Mullock Library at St. John’s. In after years he acquired the same facility and perfect knowledge of French and Italian” (11). Unfortunately, only a few volumes by Miguel de Cervantes and Francisco de Quevedo, and Jamie Balmes’s comparative study of Protestantism and Catholicism, survive from this impressive Spanish collection. Mullock also owned a handful of Greek Bibles, Greek grammars and dictionaries, a Latin-Greek edition of Homer’s works, and a fine collection of Hebrew manuals. Judging from the quality of his English-Hebrew grammar books, Mullock must have been fascinated by the language and a devoted student of it, acquiring Hebrew handbooks from his early period as a student in Spain until his later years as bishop of Newfoundland. Irish titles are conspicuously absent from the library, mainly because, as Mullock himself admitted, he did not speak the language. As Howley notes, “Fr. Mullock, though a linguist of more than ordinary versatility, did not know Irish, a thing he often regretted” (14 n.7). Mullock certainly found particular joy in applying multilingual signatures, especially in languages in which he was a fluent speaker and reader. He signed his early books variably as John, Jean, Giovanni, Joannis, and Juan T. Mullock most commonly on the title page or on a front flyleaf and occasionally at the end of the text or on a rear flyleaf.

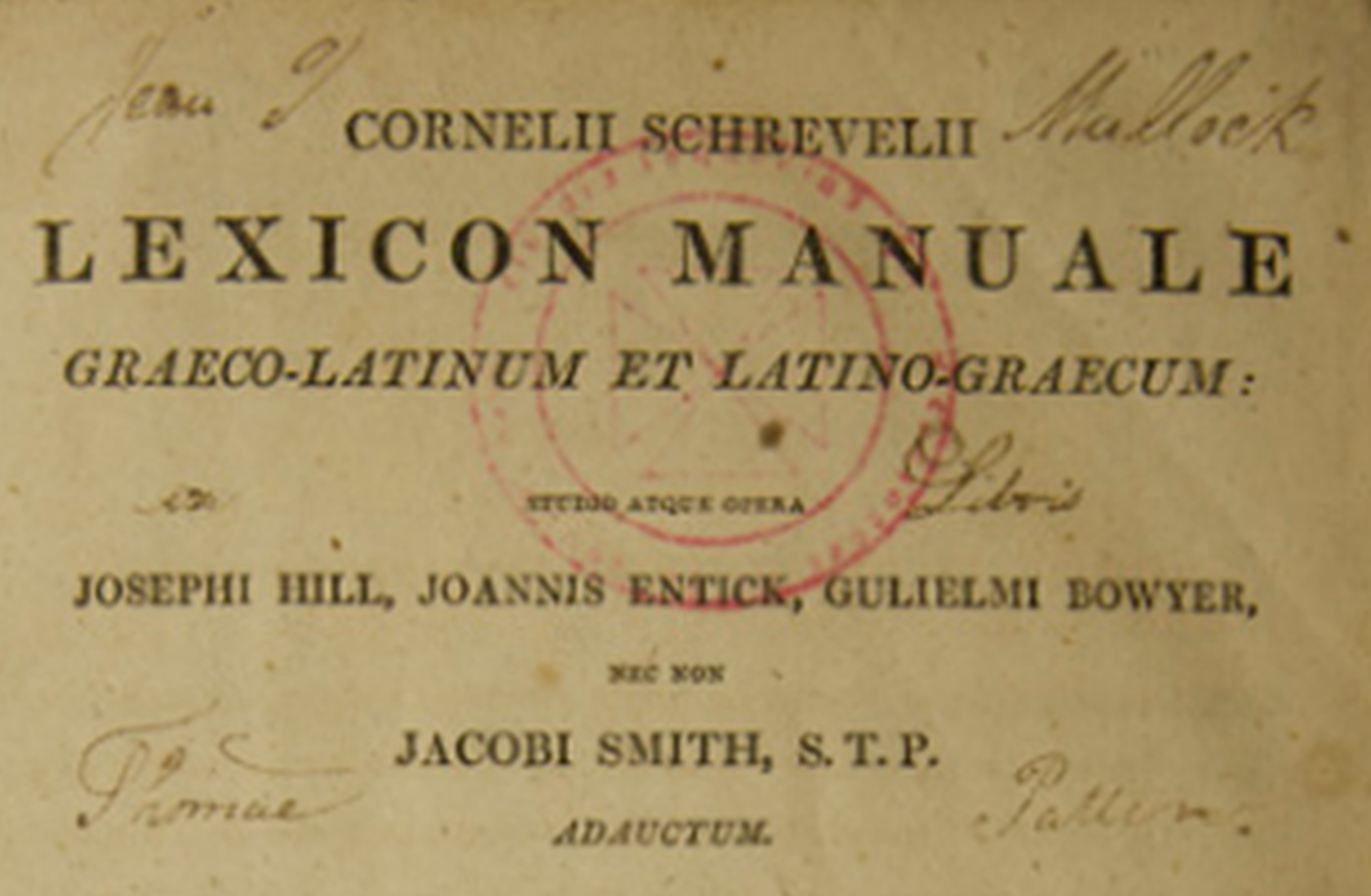

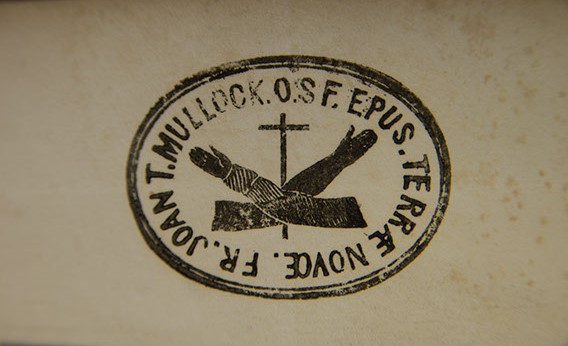

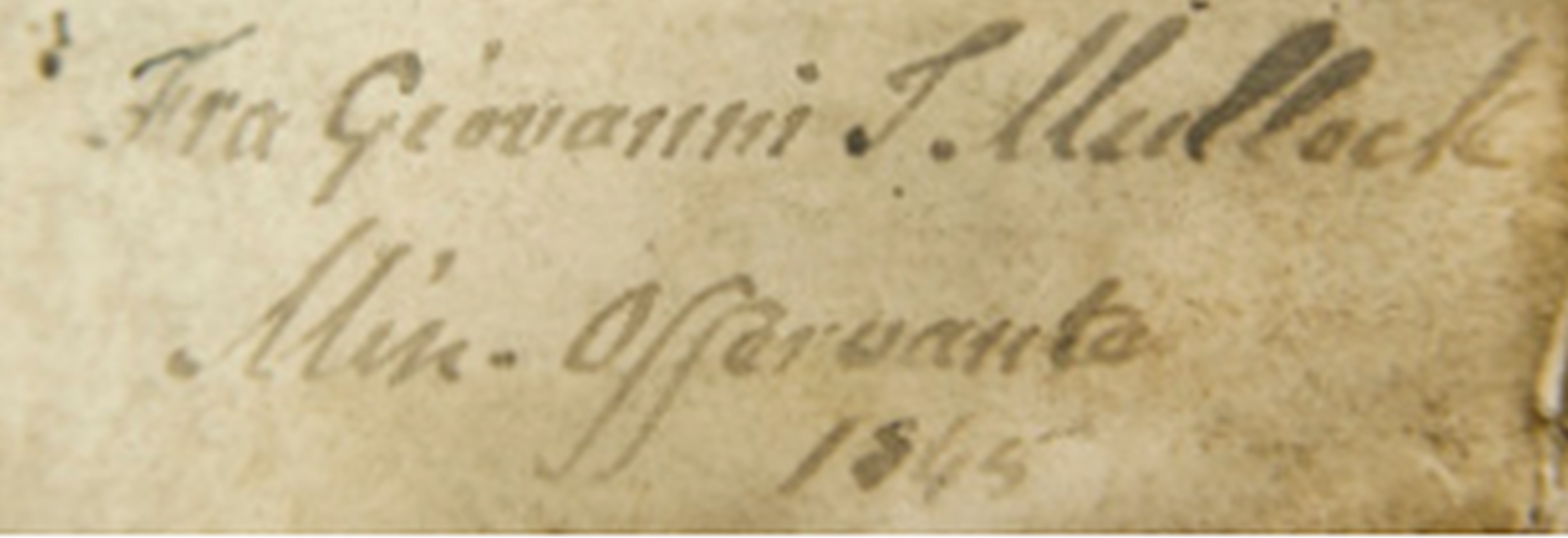

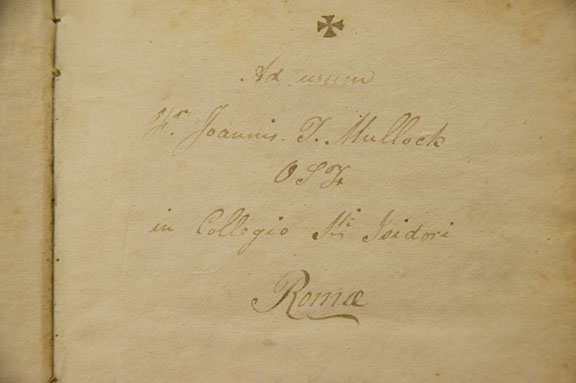

His Greek-Latin lexicon, for example, contains three different signatures, English, Latin and Greek, and one of his Hebrew manuals bears a slightly misspelled Hebrew inscription. Although he did not always do so consistently, Mullock updated his ownership marks, thus offering some tentative clues as to the dating of his purchases. His earliest signature (‘Fr[ater] Joan[nes]. T. Mullock’ O. S. F.) appears after his entry to the Order of St. Francis (Ordo Sancti Francisci) in 1825. Since, as a Franciscan, he took a vow of poverty and was not supposed to accumulate books for himself, Mullock’s signatures were often accompanied by the phrase “Ad usum,” indicating that these books were meant merely “to be used” by him, while he was in Franciscan monastic communities in Seville, Rome, and Ireland. When Mullock was ordained as a priest in Rome in 1830, he added S. P. (Sanctissime Pater or Most Holy Father) to his inscription and changed his title from friar to priest (P[ater] Joannis T. Mullock). He at times noted that he obtained a book with his superiors’ permission (sup. per.), like the three volumes of the French philosopher and Protestant writer Pierre Bayle’s foundational Dictionnaire historique et critique. Sometimes he even needed papal permission to own certain books, such as the English translation of the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s seminal Emilius and Sophia or the Protestant King James Bible. The permission was granted in the first case by Pope Pius VII and in the second case by Pius VIII (cum licentia Pii VIII P[ontifex]. M[aximus]) during his exceptionally short reign (1829–30).[ii]Mullock’s signatures also reflect his professional advancement, first as titular bishop of Thaumacene in partibus (1847–50), then as bishop of Newfoundland (1850–56), and finally as bishop of St. John’s (1856–69, following the creation of the Diocese of Harbour Grace. During his tenure as bishop of Newfoundland, Mullock introduced two Episcopal stamps: he used an oval ink stamp with his name and abbreviated Latin Episcopal title (“TERRÆ NOVÆ. FR. JOAN T. MULLOCK. O.S.F. EPUS”) surrounding the symbol of the Franciscan order: the Tau cross with two crossed arms, Jesus’s right hand with the nail wound and St. Francis’s left hand with the stigmata wound. His Episcopal stamp was later modified into an elegant round embossed stamp with his ceremonial mitre added to the Franciscan symbol.

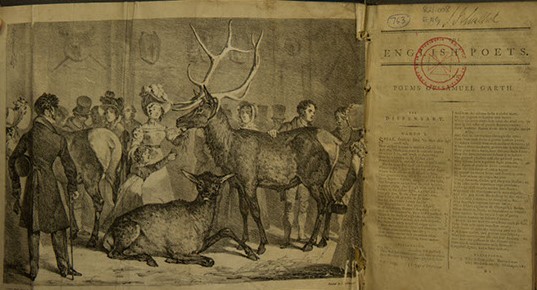

Not only did Mullock sign his books but he also regularly dated them starting from his sojourn in Spain until the end of his life. He bought books while in Dublin and while travelling in Rome, Paris, and London as the inscriptions in the books and the occasional references in his diaries confirm. [iii] Following his arrival in Newfoundland, he had a considerable number of volumes shipped from Europe (particularly Paris) to St. John’s. Mullock’s dated acquisitions constitute a diverse selection, revealing his eclectic approach to collecting. They are not restricted to his philosophical and theological studies, nor to his Liguori scholarship, nor his interest in universal and especially Irish church history, but they also include literary and secular historical works, biographies, travel books, and a broad range of journals in different languages which he obtained randomly along with other necessary professional tools. His love of literature is apparent in his choice collection of classical Greek and Latin works, eighteenth-century English poetry, French and Italian drama, William Shakespeare’s plays, and works by Spanish authors. Some early purchases suggest that Mullock’s interest in translating Ligouri’s works began in Spain and he consciously gathered primary and secondary sources long before his first English translations of Liguori’s historical accounts of the heresies or of the Council of Trent appeared in print. It was also in Continental Europe where he gathered many of the rare sixteenth- and seventeenth-century imprints he so cherished and brought with him to St. John’s.

There is a marked shift, however, in the pattern of acquisition once Mullock moved to Newfoundland in 1848 and conceived of the idea to establish a seminary and school. In the subsequent period, whole sets of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Latin, French, and Italian moral theological works, biblical commentaries, sermon collections, ecclesiastical historical encyclopaedias, and practical theological guides arrived en masse to furnish the library with studies and research tools indispensable for Mullock’s newly founded seminary.[iv]As attested by his dated inscriptions, multi-volume sets streamed into the library from Migne’s bookstore, the Parisian Atelier Catholique, year after year between 1849 and 1861 to provide a complete course (cursus completus) of Catholic theology (Entries 13, 14). Although not dated or signed as assiduously as the theological collection intended for seminarians, there is a marked increase in educational books, in particular school editions of classical Greek and Roman authors; French, Italian, Spanish, and German grammars; dictionaries; English literary works; and recent publications in history, geography, music, and natural sciences aimed at younger students. It was during this period that Alexander von Humboldt’s Cosmos: A Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe and other books popularizing the mechanical arts appeared in the collection. They were added in the 1850s and 1860s when Mullock was preoccupied with creating an ideal environment for study at St. Bonaventure’s College. His acquisitions mirror the curriculum he envisioned in his Lenten Pastoral Letter of 1857: “a good English, commercial and scientific education together with a knowledge of modern languages … the study of the ancient languages and mental and natural philosophy.”

But even when his collecting habits were so clearly focused on stocking the public and school library with essential volumes, Mullock did not abandon his own personal interests. After his move to St. John’s, his discovery and conscious reorientation toward the New World was manifested in the rapidly growing number of books he collected that were printed in or concerned with the affairs of British North America and the United States. In the turbulent years of the political upheaval of the 1860s in Newfoundland, Mullock obtained a group of French and English books on the history of the French Revolution which were, perhaps in his view, particularly pertinent to his own situation and (at times controversial) participation in local politics. Characteristic of his scholastic methods, Mullock gathered studies on the French Revolution that represented both sides of the debate, weighing the arguments for and against his examined topic. The same attitude is exhibited in the considerable amount of controversial literature in the Mullock collection which takes a defensive position about the Catholic church and demonstrates the bishop’s firm support for papal authority.

Notwithstanding Mullock’s ultramontane loyalties and overt Roman preferences in ecclesiastical matters, he gathered numerous studies on the history of Methodism, Jansenism, Jacobinism, Lutheranism, and the German Reformation, as well as writings by Quietist authors, which he clearly consulted for the footnotes of his translation of Ligouri’s History and his own supplementary chapter on the heresies of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Furthermore, he collected a substantial number of books on the English Reformation, a topic particularly close to his heart, to inform and even revise his translation of Ligouri’s History. Mullock patently displayed his rigorous approach to scholarship in his translator’s preface: “In the latter portion of the work, and especially in that portion of it, the most interesting to us, the History of the English Reformation, the Student may perceive some slight variations between the original text and my translation. I have collated the Work with the writings of modern Historians—the English portion, especially with Hume and Lingard—and wherever I have seen the statements of the Holy Author not borne out by the authority of our own Historians, I have considered it more prudent to state the facts, as they really took place; for our own writers must naturally be supposed to be better acquainted with our History, than the foreign authorities quoted by the Saint [Ligouri]” (unnumbered page).

Perhaps it was this meticulousness and curiosity of the scholar-theologian that led Mullock repeatedly to seek out authors whose works were placed by the Catholic church on the Index of Prohibited Books (Index Librorum Prohibitorum), an unusual, though not unprecedented, choice for a Victorian ecclesiastical official. Prompted by the spread of Reformation ideas through the printing press, the original indexes compiled by the faculties of theology of the Universities of Paris and Louvain in the early sixteenth century were soon followed by similar compilations in Italy, Portugal, and Spain, and were eventually codified by the first papal index issued by Paul IV in 1559.[v] Although the ever-growing list of banned books was regularly updated and revised on subsequent papal indexes until the whole enterprise was finally abolished in 1966, it is difficult to ascertain to what extent nineteenth-century Catholic readers and scholars followed, if at all, the guidance of these indexes, when selecting their reading material. Mullock certainly did not seem to have been restricted by these prohibitive lists. He owned condemned works by, among others, Niccolò Machiavelli, Erasmus of Rotterdam, Francis Bacon, Johannes Buxtorf, Hugo Grotius, Blaise Pascal, Pierre Bayle, Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, John Locke, Samuel Richardson, and Edward Gibbon.Whether it was this extensive reading list of freethinkers combined with the religious conflicts in contemporary Newfoundland that convinced Mullock to obtain Thomas Clarke’s History of Intolerance (Waterford, 1819) will remain an unresolved question. Nevertheless, if, as the full title of the work suggests, Mullock indeed reflected on Clarke's Observations on the Unreasonableness and Injustice of Persecution, and on the Equity and Wisdom of Unrestricted Religious Liberty, one of the last dated books in the collection, it represents a fitting closure to Mullock's long and versatile intellectual journey. While reflecting on Clarke's work, Mullock may have also revisited an early acquisition, which he most likely obtained while he was a young student in Spain, Bernard Picart’s seminal Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peoples du monde. Yet another banned book, the Huguenot Picart’s pioneering advocacy of religious tolerance could have proved not only a suitable accompaniment to the History of Intolerance in the public collection but also a profound private companion to the aging and ailing bishop in the final years of his life.

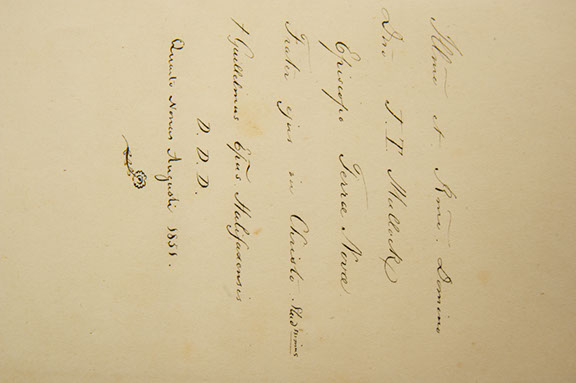

Mullock also received books from friends, associates, and publishers. These gifts are often the only remaining evidence of Mullock's personal connections with his contemporaries, among them Irish and English bishops, political sympathizers and enemies, old family friends and patrons. While studying in St. Bonaventure's College in Seville, Mullock must have built up close ties with the Dominican St. Thomas College in Madrid from where his copy of a Greek New Testament (Novum Testamentum Graece [Edinburgh, 1804]) originated. Two Spanish theological works by the sixteenth-century writer and preacher Luis de Granada were bequeathed to him by Patrick Sharkey, an Irish student at St. Thomas's in Madrid and later Dominican friar at Sligo Abbey. Apart from these Spanish bequests, the Reverend Charles Browne, an acquaintance from the Adam and Eve Convent in Dublin in the 1830s, enriched Mullock's steadily developing French collection with eighteenth-century editions of Molière's and Corneille's dramatic works, and Nicolle de La Croix's Géographie moderne. Mullock's consecration as bishop of Thaumacene in partibus in Rome in 1847 is memorialized in a Latin breviary (Breviarium Romanum), inscribed by both Mullock and the Prefect of Propaganda de Fide, Cardinal Franzoni, who officiated the ceremony. Mullock's relationship with the prominent English cardinal, Henry John Newman, is documented by a now partially lost correspondence, as well as by Newman's Discourses on University Education, which arrived, most likely as an unbound bundle, in St. John's in 1857. The records of the Halifax councils were sent to Mullock from Nova Scotia by Reverend Michael Harrison, while Mullock was kept updated about the politically significant Baltimore provincial councils by his friend, the archbishop of Halifax, William Walsh.

James Rogers, the freshly installed bishop of Chatman, New Brunswick, evidently attended Mullock's lecture “Rome, Past and Present” delivered in St. Dunstan's Cathedral in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, in 1860. A day after the lecture, his “humble and grateful friend” gave Mullock a copy of Alexander Monro's New Brunswick; with a Brief Outline of Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. Their History, Civil Divisions, Geography and Productions, published in Halifax in 1855 and signed by Rogers in Charlottetown on August 17. Another token of gratitude is found in a beautiful eighteenth-century edition of Horace, presented to Mullock appropriately enough by William Cowper Maclaurin, an Anglican convert from England, who became professor of classics at St. Bonaventure's College on Cardinal Newman's recommendation.

Inscriptions in books also point to Mullock's less known political activities. The Parliamentary Debates on the Subject of the Confederation of the British North American Provinces, published in Quebec in 1865 and sent to Mullock “by the Canadian Parliament,” contains a revealing letter by the bishop on the question of confederation. A surprisingly friendly gesture from Mullock's political opponent, the governor of Newfoundland, Alexander Bannerman, is preserved in Thomas C. Harvey's Official Reports of the Out Islands of the Bahamas. That Bannerman's present was not simply a customary act of politeness but a genuinely thoughtful gift is confirmed by Harvey's book, the main focus of which, the improvement of infrastructure in the Bahamas (the governor's previous posting), was a major concern to both Mullock and Bannerman. Mullock's interest in the development of communication and transportation in Newfoundland also brought him into contact with the American industrialist Peter Cooper, who, as president of the New York, Newfoundland and London Electric Telegraph Company, was in charge of the transatlantic cable endeavour. Apart from their interest in communications, Mullock and Cooper shared their views on progressive educational models, delineated in Cooper's complimentary contribution to the Mullock collection, Charter, Trust Deed, and By-Laws of the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. According to the testimony of his books, Mullock also closely followed current political events in Ireland. Mullock's contemporary, one of the leading Irish nationalists, William Smith O'Brien, presented him with two books after his return from exile. Following his three-month tour of North America, which included a visit to St. John's in 1859, O'Brien gave Mullock a copy of his own Principles of Government; or Meditations in Exile (Boston, 1856) which he signed in New York in May 23, 1859. A year later O'Brien sent Mullock a copy of John Donoghue's Historical Memoir of the O'Briens: With Notes, Appendix, and a Genealogical Table of Their Several Branches (Dublin, 1860), signed in May 1860.

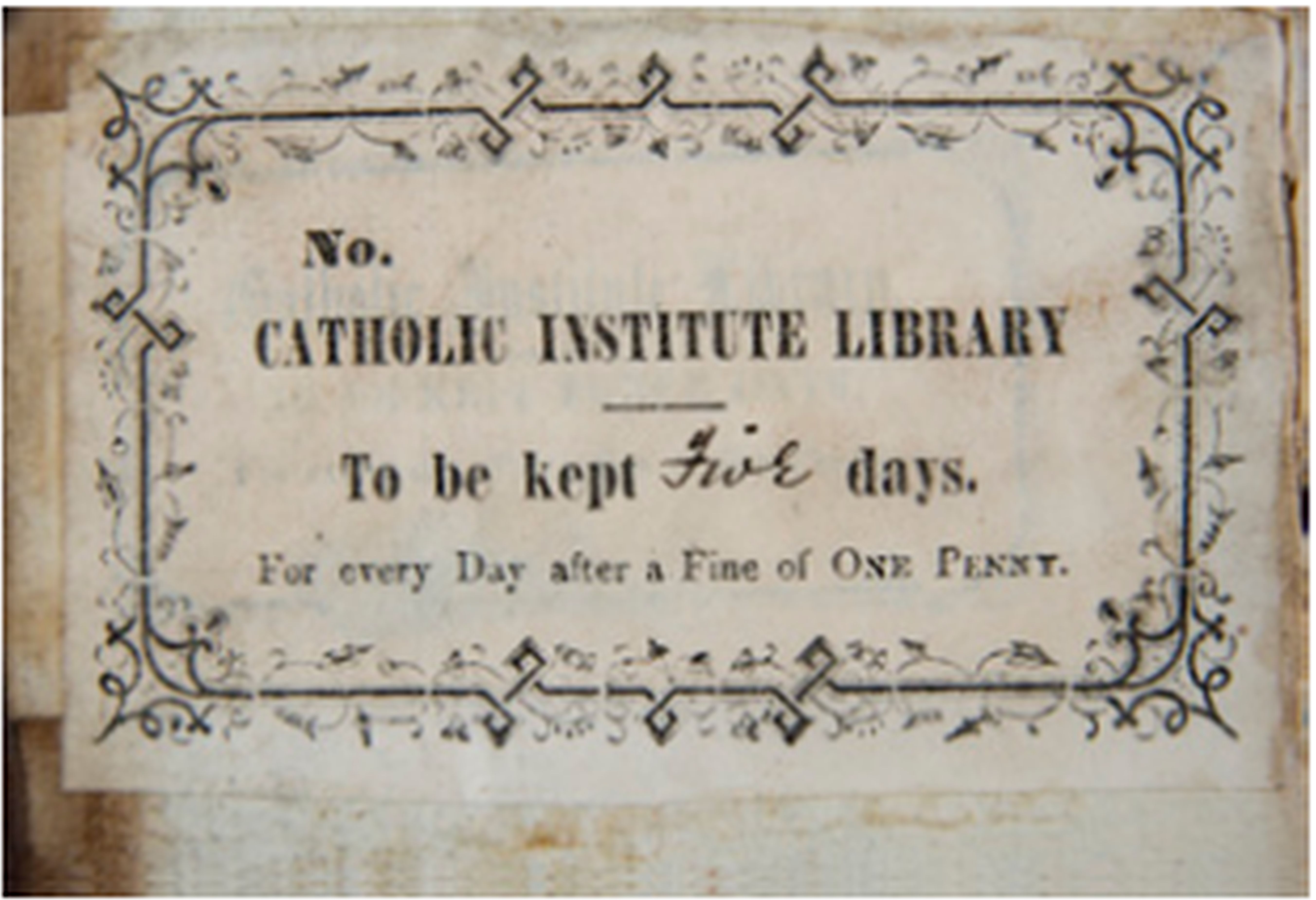

Gifts and complimentary copies were also sent to Mullock by publishers James Duffy and Gerald Bellew from Dublin. When Mullock visited Limerick and Dublin in 1849, after his first year in Newfoundland, his pianist Jane McKenna gave the relentless wanderer a Handbook for Travellers in France. Some books migrated to Mullock's collection from other institutions: René-Aubert Vertot's History of the Knights Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem (Edinburgh, 1770) came from the Dublin Lending Library; Marie Louise Prudhomme's Histoire genérale et impartiale des erreurs, des fautes et des crimes commis pendant la Révolution Française (Paris, 1797) was previously owned by Henry Fitzpatrick, the printer and bookseller of the Royal Seminary at Maynooth in Ireland from where a devotional work, Officium Beatæ Mariæ Virginis (Prague, 1797), also arrived in St. John's. Finally, a whole set of William Shakespeare's works (London, 1830) was borrowed from the Catholic Institute Library in St. John's, but (despite the five-day limit) it was never returned there.

Mullock had a clear vision of the kind of books he wished to obtain for himself and for the public library. To realize his plans, he must have regularly referred to subscription lists (particularly those of Migne's), booksellers' advertisements, and journals' miscellaneous literary notices to remain informed about recent publications. The Foreign Quarterly Review, a London-based independent journal (later merged with the liberal Westminster Review) of which Mullock had eleven issues (1832–37), contained, for example, an extensive “List of the Principal Works Published on the Continent,” arranged according to such topics as theology, philosophy, law, mathematics, physics, chemistry, natural and medical sciences, history, biography, travel, poetry, drama, novels, romances, and Oriental literature.

Yet, the most formative influence on Mullock's collecting habits came from his early years in Seville and Rome. Although it is hard to assess the holdings of the library of St. Bonaventure's College in Seville during Mullock's time there, the Wadding Library of St. Isidore's College in Rome has been a major centre of study and research from its foundation in 1622 until the present day. To accommodate the thorough spiritual and intellectual training program envisaged by the founder of St. Isidore's, the Irish Franciscan theologian and writer Luke Wadding (1588–1657), who placed special emphasis on the importance of acquiring a broad range of knowledge for Franciscans, the Wadding Library housed about 5,000 volumes at its inception in the seventeenth century.[vi]Over the centuries, the guardians of the library built up a rich collection of theological, canonical, spiritual, and pastoral works, early Christian writings, and biblical commentaries, and expanded the core areas with books in natural science, political philosophy, history, travel, and controversial literature. Significantly, just before Mullock's arrival in Rome, a substantial number of books migrated from the equally well-equipped St. Anthony's College, Louvain, to St. Isidore's in the early 1820s. In many ways, Mullock's own collection mirrors the composition of that at St. Isidore's and in certain areas there is a direct connection between the two libraries. As a student living a largely monastic form of life at St. Isidore's, Mullock had access to an abundance of books on such specialized topics as the Council of Trent and the hotly contested doctrine of the Immaculate Conception (promoted by Wadding and Ligouri), both of which feature in Mullock's own collection. The Tridentine collection at St. Isidore's may have prompted him to purchase such classics as Sforza Pallavicio's Istoria del Concilio di Trento (Rome, 1657) and whole sets of controversial writings and disputations by the Italian Jesuit Robert Bellarmine (Roberto Bellarmino), one of the most prominent figures of the Counter-Reformation.

Similar to the Irish Franciscans at St. Isidore's, who did not refrain from studying histories by Protestant writers, Mullock freely gathered all sorts of books by Anglican and Calvinist authors. It was also most likely at St. Isidore's where, following Wadding's and successive custodians' examples, Mullock was inspired to become an annalist first of the Franciscan order in Ireland and later of the church in Newfoundland. Furthermore, St. Isidore's housed an excellent map and manuscript collection so, as Joseph MacMahon and John McCafferty have pointed out in their survey of the Wadding Library's early history, a student at St. Isidore's would have been exposed to a strategically accumulated, comprehensive collection that would have inevitably affected his outlook for the rest of his life: “Being surrounded by this wealth of printed and manuscript material, reinforced by the richness of the visual art and architecture of Rome, would undoubtedly have shaped his identity and added a new dimension to it. Being an Irish Catholic meant, not only being part of a subject people, but also of belonging to a powerful international body and tradition. It is easy to see how ‘Irishness' and ‘Catholic' were being irrevocably forged into a unified identity and how the latter dimension expanded one's mental horizon beyond the narrow restraints of the national and local. To be Catholic was also to be European and cosmopolitan” (116).

When Mullock disembarked from the steamer Unicorn with an enormous coffer packed with English, French, Spanish, Italian, Latin, and Greek books and Hebrew grammars in St. John's harbour on May 6, 1848, it was this cosmopolitan ideal accented by a strong southern European flair that he brought with him to his new home, an ideal he subsequently attempted to transplant into his educational foundation and library. Like many Victorian readers, Mullock cherished the aesthetic of the pristine, unspoiled page, and he rarely annotated or marked up his books. It does not mean, however, that he did not read them. In fact, his frequent references in his writings and translations to volumes in the Mullock collection suggest that he regularly consulted many of them. Some favourites he took with him on his travels. Mullock signed his copy of Modern British Essayists first in 1850, then he apparently amused himself with his work, which included the essays, among others, of the British historian and Whig politician Thomas Babington Macaulay (whose books he avidly collected) in Chateaux Bay, Labrador, in 1852.

Despite his dedicated collecting that spanned a lifetime and encompassed books published from 1524 until 1868, Mullock was not technically a bibliophile. Neither did he indulge in deluxe editions or expensive fine bindings, nor did he hunt for exquisite illustrated books or first editions. Interestingly, the only instance when Mullock seemed to have paid special attention to the bibliographical features of his acquisition is when he purchased in Rome in early 1848 the breviary he gave as a gift to Bishop Fleming. Covered in beautiful gold-tooled leather binding with fine metal clasps, the Mullock-Fleming breviary is a superb example of nineteenth-century Belgian book production. Yet the majority of the Mullock collection consists of affordable books and reprints clad in vellum (typical of student bindings), calf or goat skin, quarter leather binding with marbled paper on the boards, canvas-type cloth, or, occasionally, plain blue paper wrappers.

His definition of rare and valuable was largely limited to the content of his acquisitions and to his antiquarian predilection for early printed books. Among his earliest purchases are rare imprints from the print shop of Johann Knoblouch in Strasbourg (1524), Eucharius Cervicornus in Cologne (1524), Johann Herwagen in Basel (1536 and 1539), Michael de Roigny in Paris (1551), Artus Chauvin in Geneva (1562), Giovanni and Giovanni Paolo Gioliti de’ Ferrari in Venice (1581), Cornelio Bonardo in Salamanca (1588), and Jan Janssonius in Amsterdam (1626). Mullock also had two copies from the famous Officina Platiniana operated by Balthasar II Moretus in Antwerp (1657). Places of publication of Mullock’s later books also vary widely, representing all major centres of printing in Europe and North America. The collection Mullock offered to the public in 1859 constitutes a colourful assortment of highly personal and private as well as professional and public books.[vii]While they showcase the versatile interests of a scholar and theologian with a marked Irish, British, and Continental European background, they also demonstrate Mullock’s unfailing and untiring commitment to education in his new place of ministry, Newfoundland, which he would routinely and fondly refer to as his country.

Footnotes

[i] Bishop John Thomas Mullock, Journal of the House of Assembly Appendix, Education, December 31, 1859.

[ii] Since Pius VII died in 1823, it is more likely that it was Pius VIII who granted the permission, just as he did in the case of Mullock’s copy of the King James Bible.

[iii] In his diary for 1851 recording his trip to Halifax, Montreal, London, Paris, Rome, and Ireland, he notes that he bought, among other things, books in London.

[iv] According to Michael F. Howley, “The stocking of the [Episcopal] library may also be guessed from some of the bills. Thus we find: The Ballandists’ [sic] Acta Sanctorum Vols. £27.13.6 pounds, Abbe Migne’s Patrologia Graeca et Latina Vols. £145.11.0, Vaticano Vols. £30” (Ecclesiastical History of Newfoundland, Volume Two, ed. Joseph B. Darcy, assoc. ed. John F. O’Mara [St. John’s, 2005], 80).

[v] See Jésus Martinez de Bujanda, Index des livres interdits, 10 vols. (Sherbrooke and Geneva, 1984–96) and Index librorum prohibitorum (1600–1966) (Montreal and Geneva, 2002); cf. Pearce J. Carefoote, Forbidden Fruit: Banned, Censored, and Challenged Books from Dante to Harry Potter (Toronto, 2007).

[vi] See Joseph MacMahon and John McCafferty, “The Wadding Library of Saint Isidore's College Rome, 1622–1700,” Archivum Franciscanum Historicum 106 (2013): 97–118. Cf. Benighnus Millet, “The Archives of St. Isidore's College, Rome,” Archivium Hibernicum 40 (1985): 1–13. For Irish Franciscan libraries, see Canice Mooney, “The Franciscan Library, Merchants' Quay, Dublin,” An Leabharlann: Journal of the Library Association of Ireland 8 (1942): 29–37 and “The Irish Franciscan Libraries of the Past,” Irish Ecclesiastical Record (1942): 215–28.

[vii] The primarily theological collection of the Roman Catholic bishop of Victoria Charles John Seghers (1839–86) provides an interesting comparison with Mullock's collection. On Seghers's books see more in Hèléne Cazes, The Seghers Collection: Old Books for a New World (Victoria, BC, 2013).