Mullock as Author and Translator

At the time of Bishop Mullock’s death in 1869, a writer identified as E. J. P. wrote in a local newspaper, “No scholar living in [Mullock’s] time possessed a larger fund of universal knowledge, or mental faculties more perfectly developed.[i] As this and other tributes attest, John Thomas Mullock was renowned for his intellect and learning. His reputation as a scholar was due not primarily to his establishment of St. Bonaventure’s College and the Episcopal Library but to his record as a speaker, author, and translator.

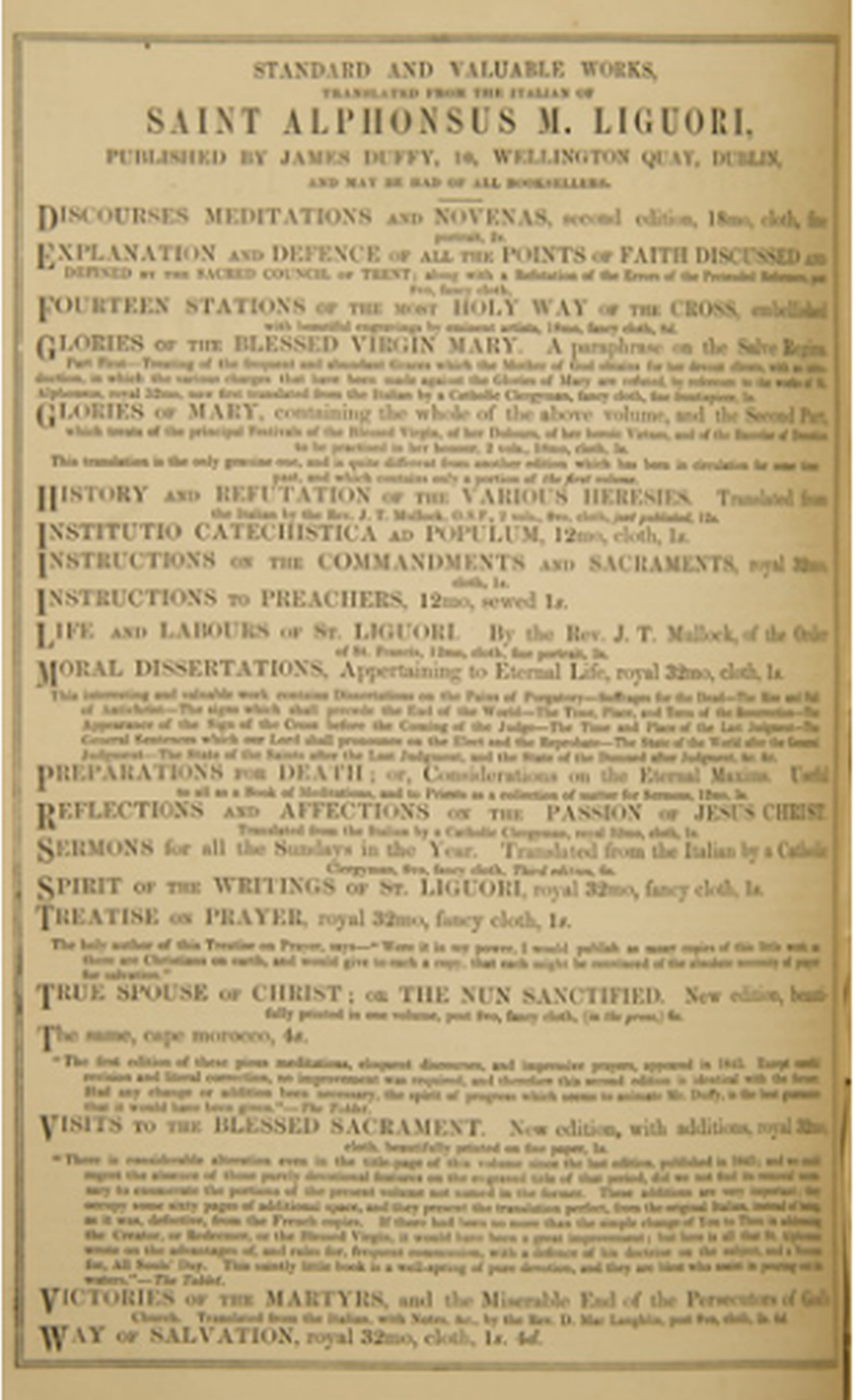

There is no definitive bibliography of Mullock’s works, as it is likely that he published more texts anonymously than have been identified. One possible gap is revealed by Edward Morris, who asserted in 1931 that Mullock produced translations from the Italian and Spanish,[ii] as today there is no evidence of Spanish translations. Mullock did have a longstanding scholarly interest in the life and work of the Italian bishop Alphonsus de Liguori (1696–1787) and translated at least one title by him, The History of Heresies and Their Refutation, in 1847, but numerous other Alphonsian translations of all kinds were being issued by Mullock’s publisher, James Duffy of Dublin, around this time. At least two other translators, Nicholas Callan of Maynooth (1799–1864) and Louis de Buggenoms (1816–82), were active during this period, and both attributed their translations to “A Catholic Clergyman,” as was common for ordinary priests.

In terms of anonymous Liguori translations, a question mark must be added next to Liguori’s book on the Council of Trent translated by “A Catholic Clergyman” and published by Duffy in 1846,[iii] which John Gushue, in a 1988 unpublished essay, identified as a possible Mullock work.[iv] Support for this claim is provided by Mullock’s book collection, which contains a conspicuous number of French and Italian titles on the Council of Trent: counting the books that do not bear Mullock’s signature or stamp, there are nearly twenty volumes on the subject published between 1738 and 1844 in the Episcopal Library. In addition to this title, it is possible that Mullock translated some of Liguori’s devotional works as well. We do know that Mullock published anonymously at least once. His diary records that he was the translator of a work by (or attributed to) Father Hugh Ward (1592–1635) called “A History of the Irish Franciscans,” which appeared in installments in Duffy’s Irish Catholic Magazine in 1847. Mullock likely became acquainted with Ward’s manuscript, which was held at the Irish Franciscan College of St. Isidore’s in Rome, during his theological studies there from 1829 to 1830. Mullock continued his research into the history of the Franciscans during his time in Cork from 1837 to 1843. Notebooks containing Latin transcriptions of manuscripts, as well as material in English, remain today in the Franciscan Library, Killiney, in Ireland and the Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St. John’s in Newfoundland, respectively.[v] Mullock’s research is evident in his translation of Ward’s “History,” which includes extensive footnotes supplementing Ward’s text with other sources and offering Mullock’s own accounts of the churches and friaries Ward describes.

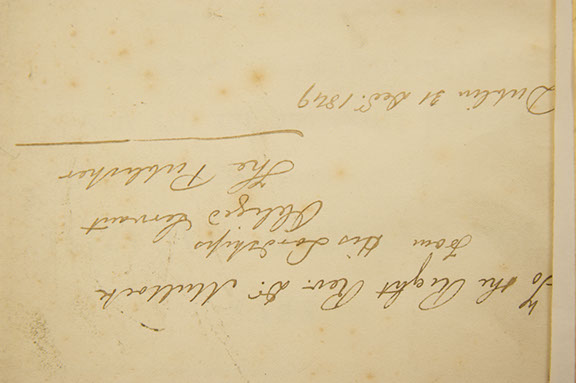

The first titles to which Mullock’s name is attached are two books relating to Alphonsus de Liguori. Mullock’s The Life of St. Alphonsus M. Liguori, Bishop of St. Agatha, and Founder of the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer (1846) and his translation of Liguori’s The History of Heresies and Their Refutation; or, The Triumph of the Church (1847; 2nd ed. 1857) are discussed by Anne Walsh in detail (Entries 15 and 16), so a brief publishing history of these volumes will suffice here. The Life was first issued by Duffy in a high-quality edition selling for two shillings in 1846. It is likely Mullock began this work around 1843: his diary notes that he produced it “during the few spare hours [he] had” while he was guardian of the Franciscan convent of Adam and Eve, Dublin. A 1862 edition of the Life by the same publisher was issued as part of a series called the “Young Christian’s Library.” These pocket books were advertised as “beautiful volumes, handsomely bound in cloth, lettered in gold, for Presents, School Prizes, &c.,” which sold for the affordable price of twopence each. Duffy issued a third edition of the Life in 1877. The History of Heresies was published in book form in two editions by Duffy: the first in 1847 was a two-volume set, which sold for twelve shillings, while the second a decade later was a one-volume edition. Subsequent to Mullock’s death, both books were issued by American companies: the Life was published in several editions (1874; 1886; 1896) by New York’s P. J. Kenedy, a publisher who catered to the burgeoning Irish-Catholic American community, and The History of Heresies by Wipf and Stock of Eugene, Oregon (2004).

The Dublin-based James Duffy (1809–71), a leading publisher specializing in Catholic and Irish national literature, published all Mullock’s works during this period. Established in 1838, Duffy’s business was one of the few Dublin publishing companies that endured through the lean years of the late 1840s and beyond. Duffy’s survival was due to his business acumen (his list ranged widely in production quality and pricing, allowing him to reach multiple audiences), as well as his “pioneering” activity in the publishing of periodicals.[vi] Mullock’s original and reprinted work appeared in two of the numerous periodicals Duffy produced: as previously noted, “A History of the Irish Franciscans” was published in Duffy’s Irish Catholic Magazine (subtitled A Monthly Review Devoted to National Literature, Ecclesiastical History, Antiquities, Biography of Illustrious Irishmen, Military Memoirs, etc.), a high-quality monthly magazine offering “an ambitious alliance of culture and religion” that ran from 1847 to 1848, while The History of Heresies was reprinted under the title “A History of Protestant Heresy” in The Catholic Guardian: or, The Christian Family Guardian, a cheap weekly noted for its improving literature, which ran from February to November 1852.[vii]

Mullock and Duffy’s relationship continued after Mullock left Ireland in 1848. Duffy would go on to publish Mullock’s booklet The Cathedral of St. John’s, Newfoundland, with an Account of Its Consecration in 1856. Mullock believed that Irish and European audiences would be keen to learn of thriving Irish Catholic institutions in the New World; he in fact assured his flock in St. John’s that accounts of the consecration had been published all over Europe in various languages.[viii] After The Cathedral of St. John’s, Mullock’s last publication with Duffy, however, there is a notable shift in the bishop’s envisioned readership. From 1860, Mullock produced his sermons and lectures for North American audiences.

In 1856, Mullock began an ecclesiastical history of Newfoundland, entitled “Memories of the Catholic Church in Newfoundland,” the first part of which remains today among Mullock’s papers in the Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St. John’s. This unpublished manuscript formed the basis of the two lectures on Newfoundland that Mullock delivered in the winter of 1860, and which stand today as his most secular literary undertaking.

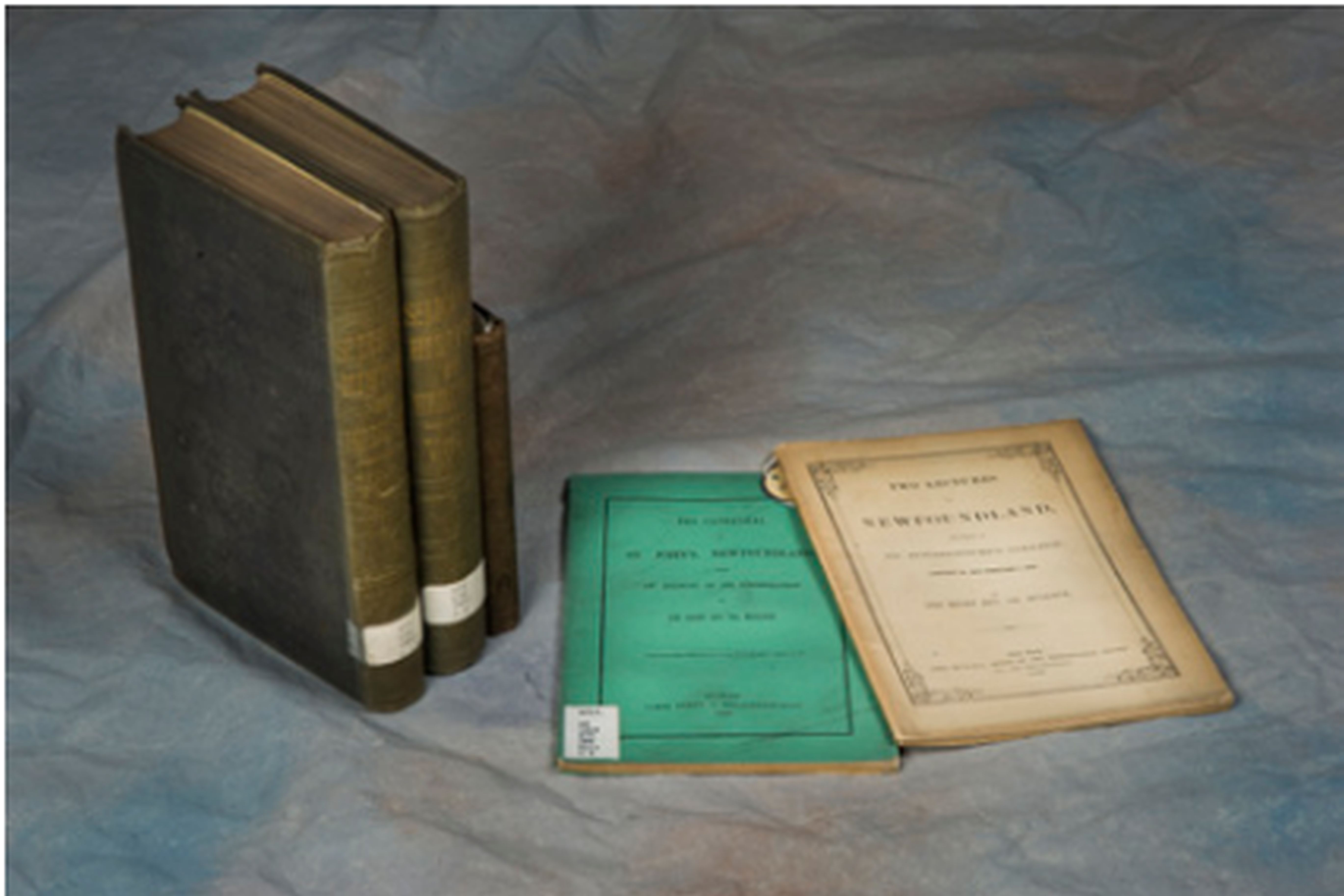

Mullock’s lectures were published twice in 1860. In St. John’s, the pamphlet Lectures on Newfoundland was printed and sold for one shilling at the office of the Patriot, a local liberal newspaper published by the Protestant and ardent Newfoundland patriot Robert J. Parsons (1835–83). In New York City, Two Lectures on Newfoundland Delivered at St. Bonaventure’s College January 25, and February 2, 1860 was published by John Mullaly at the office of the Metropolitan Record, a newspaper published by the Catholic church. Both John Hughes, the archbishop of New York, and Mullaly had visited Newfoundland just five years earlier in 1855, the former at Mullock’s invitation for the consecration of the cathedral, and the latter to witness the laying of the Atlantic telegraph cable, another undertaking dear to Mullock’s heart. It is likely that Mullock arranged for the publication of the lectures during his visit to Hughes in New York in May 1860.

While Mullock was said to have given an annual lecture at St. Bonaventure’s College, only these lectures and one other, delivered on January 24, 1861, entitled “The Catholic Church: Its Present State,” survive.[ix] Although the Newfoundland lectures may have been drawn from a projected ecclesiastical history, they go well beyond a history of the church. While the first lecture details the discovery and history of Newfoundland, paying considerable attention to the history of Catholicism, the second discusses “the physical description of the country, its climate, its capabilities, [and] its future prospects.”[x]

The lectures reveal Mullock’s wide-ranging intellect and progressive attitude. They convey his thorough knowledge of the history of Newfoundland, as well as his personal acquaintance with every corner of the region. Speaking knowledgeably on geography; geology; the salmon, cod, and seal fisheries; and agriculture, Mullock identifies untapped and underdeveloped industries, from mining and textile production to the drying and pickling of caplin. For Mullock, all that was lacking to realize Newfoundland’s potential was the necessary population, and this, he believed, would take care of itself through continuing immigration. Extracts of Mullock’s lectures were picked up by British newspapers and periodicals, notably The Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle (vol. 29, 1860), which reprinted passages on Newfoundland’s militarily and commercially strategic location, as well as its mineral resources, climate, seal fishery, agricultural practices, and peaceable population.

Another “edition” of the Newfoundland lectures is also worth noting. Mullock’s text formed the basis of the so-called biographical sketch that appeared, along with the bishop’s photograph, in William Notman’s Portraits of British Americans, with Biographical Sketches by Fennings Taylor, Volume 1 (Montreal: William Notman, 1865). The timing and place of publication of this book is interesting given the Canadian confederation of 1867. Extracts of Mullock’s lectures account for almost a third of the chapter on Mullock and largely inform the rest. Mullock’s chapter is the only one centring on a Newfoundlander in Notman and Taylor’s two-volume work, whose overall purpose was, in the words of the historian Robert Lanning, to illuminate “the historical journeys of Canada’s great men at the juncture of Confederation.”[xi] For readers aware that Newfoundland did not enter the Canadian confederation until 1949 and that Mullock’s attitude toward the idea was ambivalent (Entry 41), the bishop’s inclusion here is intriguing. The publication of the Newfoundland lectures in St. John’s, New York, and Montreal suggests that Mullock was publishing strategically, promoting his vision for Newfoundland and his own authority in three centres of political and economic power.

Unlike in the case of Mullock’s Liguori scholarship, for which the Mullock collection retains many of Mullock’s source texts, his sources on Newfoundland history are not so easily located. In his manuscript, for example, Mullock refers to “a foolish and bigoted piece of [anti-Catholic] declamation” in Lewis Amadeus Anspach’s A History of the Island of Newfoundland (London, 1819; 2nd ed. 1827). This title is not to be found in the Mullock collection today, although Mullock’s published lectures clearly draw on the earlier work’s content and structure. Even more tantalizingly, in his lectures Mullock cites a 1560 world atlas by the Florentine writer Rucellai, whose “very imperfect” map of Newfoundland and short description of the Beothuk people were rife with errors. It is not known where Mullock viewed this rare work. In both cases, he cites sources which he wishes to correct, suggesting he might have been less likely to name those whose information he found persuasive, making such works difficult to identify. One exception is Mullock’s source for his discussion of the Viking discovery of Newfoundland. For this content, Mullock gestures toward the successive translations of “Professor Rafn” and “Mr. Beamish of Cork” and thus seems to have drawn directly on North Ludlow Beamish’s important work Discovery of America by the Northmen in the 10th Century (London: T. & W. Boone, 1841). This volume does in fact reside in the Episcopal collection, but is not signed or stamped by the bishop.

The second Newfoundland lecture, with its more contemporary and scientific focus, references a sprinkling of published works and current discoveries. In his discussion of mineral resources, Mullock alludes to the “gold matrix, as described by Humboldt and others” (35); in his explanation of the route of the Gulf Stream, he references “the deep sea soundings of Captain Berryman” (39), transatlantic soundings that had been conducted prior to the laying of the transatlantic cable in the 1850s. When characterizing the Newfoundland climate, Mullock cites “the climate table furnished [him] by Mr. Delaney” (42), as well as the observations of “Abbe Raynal” (43). John Delaney was the local public servant and amateur scientist who recorded Newfoundland’s weather data for the Smithsonian Institution between 1857 and 1864; Guillaume-Thomas Raynal (1713–96) was a French Enlightenment thinker, whose works are included in the Episcopal Library in eighteenth-century volumes not signed or stamped by Mullock. The information drawn from unspecified archaeologists, ethnologists, and naturalists remains to be attributed.

While Mullock identified few of his sources for any of his published lectures and sermons, his research methods were seemingly exhaustive, taking him beyond his own book collection. In Rome, Past and Present (1860), published and apparently composed in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, he claims to be working from memory and not from his books.[xii] In Two Lectures on Newfoundland, he explains he “rapidly sketched the history of the country from the earliest records [he] could find down to the period within the memory of thousands in St. John’s” (27). This sentence suggests research into primary documents (which he characterizes as “those of an infant people, few and uninteresting to any one but ourselves and posterity” [29]), and possibly oral history. The only archives Mullock references by name are the archiepiscopal archives of Quebec; in his manuscript he explains that Archbishop Pierre-Flavien Turgeon (1787–1867) furnished him with relevant copies from that collection.

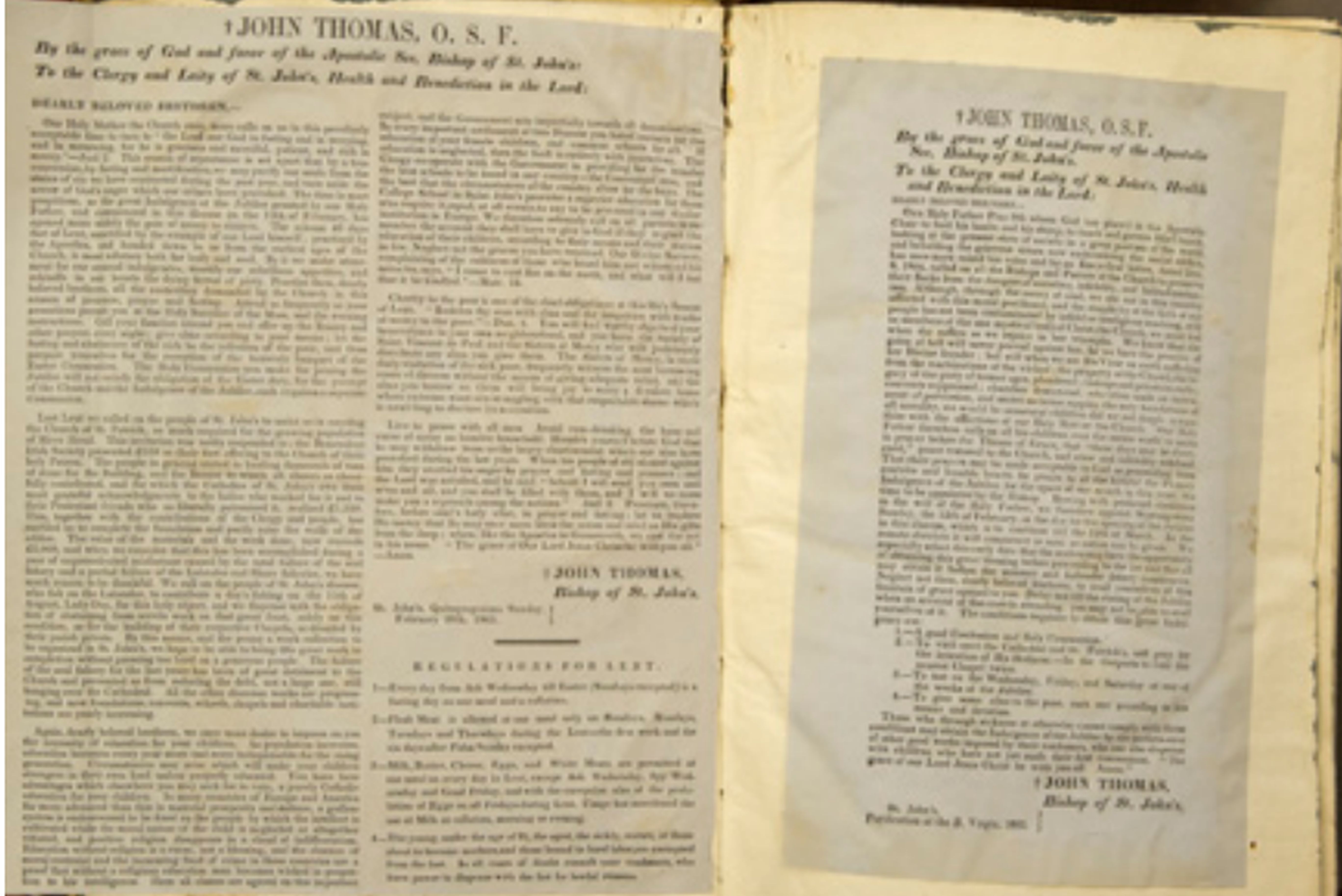

While the research material for Mullock’s works of the 1860s is a gap in the Mullock collection today, an even more conspicuous absence is a complete collection of the bishop’s own body of work. We suggest, however, that there was once an intact collection, as the bishop was clearly intent on adding a record of his own writing to the library. In over two dozen volumes (apparently selected at random for their large format), Mullock pasted one and sometimes several of his pastoral and circular letters, his letters to newspapers, and other ephemeral material relating his activities. The copy of A Sermon Preached by the Right Rev. Dr. Mullock, Bishop of St. John’s, Newfoundland, in the Cathedral of St. John’s, on Friday, May 10th, 1861 (St. John’s: Bernard Duffy, “Record” Office,” [1861]), pasted in a 1856 volume of Jacques-Paul Migne’s Collection intégrale, is today the only original copy of this pamphlet held by the Episcopal Library. Given this careful preservation of his own works in volumes which were otherwise kept in pristine condition, we can conclude that the bishop saw his own writing as a valuable contribution to the body of knowledge he was building.

Footnotes

[i]Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St. John’s, Mullock fonds, 104/1/1.

[ii]Lord [Edward] Morris, "Seventy-Five Years of Educational Triumph," The Adelphian (1931), 108.

[iii]St. Alphonsus M. Liguori, An Exposition and Defence of All the Points of Faith Discussed and Defined by the Sacred Council of Trent: Along with a Refutation of the Errors of the Pretended Reformers and of the Objections of Fra Paolo Sarpi (Dublin: Duffy, 1846).

[iv]John Gushue, "The Personal Library of John Thomas Mullock, Bishop of Newfoundland: An Incomplete Short-title List" (1988), Centre for Newfoundland Studies, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

[v]Mullock's 1838 Cork notebook is held in Dublin, Franciscan Library, Killiney, Ms. Section M, in the collection "Note-books including diaries of Rev. P. F. O'Farrell, 1854 and A. Holohan, 1879, missionaries in Australia, and note-books of Rev. J. T. Mullock, afterwards a bishop in Newfoundland, and of Rev. R. L. Browne and E. B. Fitzmaurice and other Irish Franciscan historians." Mullock's 1840 notebook is held in Archives of the Archdiocese of St. John's, Mullock fonds, 104/2/2.

[vi]Rolf Loeber and Magda Stouthamer-Loeber, "James Duffy and Catholic Nationalism," in The Oxford History of the Irish Book, Volume IV: The Irish Book in English 1800-1891, ed. James H. Murray (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 115-.

[vii]Elizabeth Tilley, "Periodicals," in The Oxford History of the Irish Book, Volume IV: The Irish Book in English 1800-1891, ed. James H. Murray (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 166.

[viii]Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St. John's, Mullock fonds, 104/1/41. Pastoral Letter (14 July 1856).

[ix]Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St. John's, Mullock fonds, 104/3/1, "Scrapbook."

[x]John T. Mullock, Two Lectures on Newfoundland Delivered at St. Bonaventure's College January 25, and February 2, 1860 (New York: John Mullaly at the Office of the Metropolitan Record, 1860), 29. All page references are to this edition.

[xi]Robert Lanning, "Portraits of Progress: Men, Women and the 'Selective Tradition' in Collective Biography," Journal of Canadian Studies 30 (Fall, 1995): 38-59.

[xii]Rome, Past and Present; A Lecture Delivered in St. Dunstan's Cathedral, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, on Thursday, August 16, 1860 was first published in the Charlottetown newspaper The Examiner (Archdiocese of St. John's Archives and Records, Mullock fonds, 104/3/1, "Scrapbook") and then in pamphlet form by the newspaper's publisher in October 1860.

.