Frederick Menzies Donations to Queen’s College Library

Frederick Menzies was born in Wavertree, Lancashire, in 1815 to merchant John Menzies and his wife, Mary Anne (née Gardiner or Gardener). His exact date of birth is not available, but he was christened at St. Michael-in-the-Hamlet in Aigburth, Lancashire, on 15 November 1815. He was the youngest of eight siblings. From oldest to youngest were Anne, Henry, John, William, Caroline, Alfred, Lucy, and Frederick. Both William and Alfred also became priests. His nephew, through his brother Henry, was the architectural designer and carver John Henry Menzies.

Menzies began to attend Brasenose College in Oxford on 5 December 1833 at the age of 18. He received his BA in 1837 and his MA in 1840. During his college years, he received both scholarships and titles, including the Kenicott Hebrew scholarship in 1838. He was a fellow of the college from 1837 to 1867. He later became vice-principal of Brasenose in 1858; he held this position until at least 1865, but the exact duration is unclear. According to records, he was also a junior bursar, Hebrew lecturer, and Hulme lecturer in divinity. Following the completion of his master’s program at Brasenose, Menzies served as curate of Hambledon, Bucks, from 1840 to 1850, and rector of Great Shefford, Berks, from 1866 to 1887. He became canon of Christchurch in 1880, possibly until his death. He died on 27 March 1901.

Reverend Frederick Menzies was an English priest and one of the most prominent donors to the Queen’s Collection. His was the most extensive bequest that filled the need expressed by Newfoundland clergy in the late nineteenth century for more recent editions of the church fathers’ works. Menzies donated 92 volumes. They comprised full sets of the works of Anselm, Eusebius, Tertullian, Cyprian, Chrysostome, Ambrose, Jerome, Basil, and Justin. Although at the time of the bequest, Menzies was honorary canon of Christ Church Cathedral, and evidently a devout Anglican (whose donation included a Book of Common Prayer translated into Hebrew and published by the Society for Promoting Christianity among the Jews), he did not refrain from seeking out Catholic editions. Among his gifts are volumes from Mullock’s main French book supplier, Jacques-Paul Migne’s popular Patrologia Latina series, complemented with the Flemish Jesuit biblical scholar Cornelius a Lapide’s reputed commentaries on the Old Testament. The latter, as the Diocesan Magazine highlighted, were in excellent condition “in the original stamped hogskin with clasps.”

As for Menzies’s relation to Newfoundland, there appears to have been a connection between him and Llewellyn Jones, an Anglican bishop of Newfoundland. According to a Daily News clipping dated October 4, 1899, it was during a trip to England that Jones met with Menzies, who subsequently offered to make a donation to the college. Books in the Queen’s Collection bearing Menzies’s nameplate are dated during the time that Jones served as active bishop, further supporting the idea that donated reading material to help develop Newfoundland’s Anglicanism. The two men were familiar with one another during their respective years in education. Menzies was a member of Brasenose College and Jones received his education at Trinity College. Both colleges were associated with Oxford, where Menzies later became a canon and was involved in the university as a representative of Brasenose College. Jones would have been aware of Menzies because of his own standing in the Anglican church as a bishop, even though the two lived on separate continents. There is also a possible family connection between Menzies and Jones. In his will, Jones left a pastoral cross to his son Nigel Eames Field Jones that he originally obtained from Alfred Menzies Jones. The combination of Alfred’s last two names suggests that he either married into the Jones family or that his parents came from both families. Little can be found on Alfred’s background, as there are several instances of the name Alfred Menzies that correspond with either Frederick Menzies or Llewellyn Jones. Alfred does appear in the roll of subscribers in the “Red and White Book of Menzies” alongside F. Menzies, showing that the two men were a part of the same family. Alfred’s relationship to Jones is unknown, but his donation of a cross to the bishop demonstrates that he did support him.

There is insufficient evidence to determine how Jones knew either of these men or even if these two theories are correct. More archival research is needed to fully substantiate these claims or to explain how Jones was involved with the Menzies family. Archival research has been hindered because Jones dictated to his executors in his will to have all of his personal correspondence destroyed. Jones did not divulge the reason for a request, but it has resulted in very little information on his contacts, aside from official circulars sent out to the local clergy in Newfoundland or documents listing the consecration of priests. Official documentation did not list any information about the Queen’s College Collection or about whom Jones may have contacted to support his ecclesiastical activities. However, as The Daily News states, the bishop of Newfoundland—who, at the time, was Llewellyn Jones—travelled to England and met with Menzies. Menzies voiced his desire to donate his books to Queen’s College, and Jones accepted the offer.

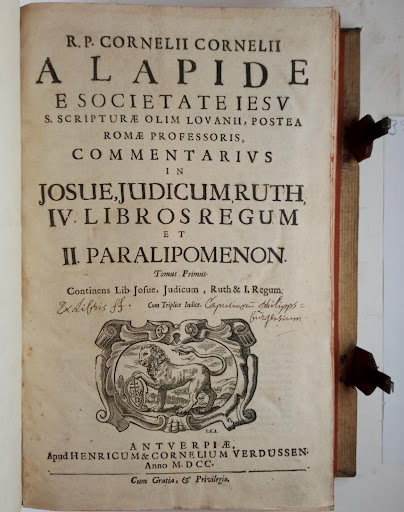

A majority of the texts donated by Menzies are theological, historical, or both. The aforementioned commentaries of Cornelius a Lapide are a significant theological donation. In these nine volumes, Lapide analyzes and discusses the Bible through a historical and scientific lens and explains and promotes piety and pious meditation, especially pulpit exposition. In English, these volumes as a whole are often referred to as Lapide’s Great Commentary. Lapide edited the first volume, his Commentaria in Omnes Divi Pauli Epistolas, in 1614, and the last volume was edited by others after his death in 1637. These commentaries covered all books of the Catholic canon of Scripture except Job and the Psalms; others wrote commentaries for these two books later and, with this done, the complete series of commentaries appeared in Antwerp in 1618.

In the commentaries, Lapide explains the literal, allegorical, tropological, and anagogical sense of the Catholic canon of Scripture, including apologetics. They also contain many quotes from the church fathers and later interpreters of Holy Writ of the Middle Ages. Lapide’s intention was not only to analyze and discuss the Bible through a historical and scientific lens but also to explain and promote piety and pious meditation, especially pulpit exposition. His work, considered so scholarly and complete that for centuries it was practically the universal Catholic commentary, has been praised by Catholic theologians and scholars such as St. Robert Bellarmine, Dom Guéranger, Denis Fahey, Leonard Feeney, and Scott Hahn. In fact, Lapide’s commentaries are held in such esteem that the first partial translation of them was done by Thomas Mossman, an Anglican, in the nineteenth century.

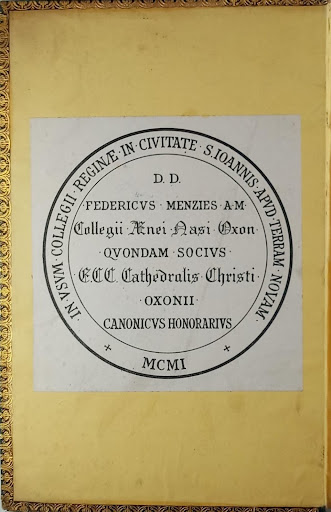

The versions of Lapide’s commentaries found in the Queen’s Collection were published between 1634 and 1714, with all but two having been published during the eighteenth century. The earliest was published in 1634 by Apud Martinum Nutium, the rest by H. & C. Verdussen, referred to in some volumes as Apud Henricum & Cornelium Verdussen. All volumes were published in Antwerp (written as “Antverpiae” in most volumes). The material is stamped hogskin and the volumes have clasps. All volumes bear the bookplate “D. D. FEDERICVS MENZIES A M Collegii Ænei Nasi Oxon QVONDAM SOCIVS F. CC. Cathedralis Christi OXONII CANONICVS HONORARIVS,” with “IN VSVM COLLEGII REGINIE IN CIVITATE S. IOANNIS APVD TERRAM NAVAM MCMI” around the bookplate, indicating past ownership by Frederick Menzies.

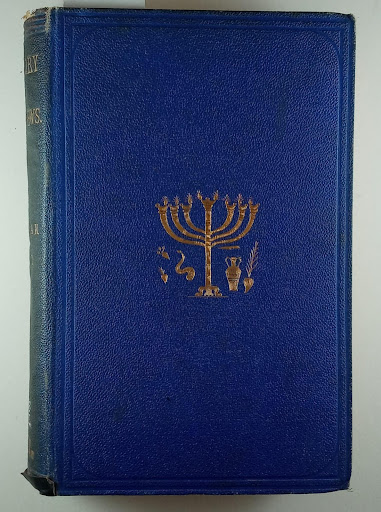

Another donation, which does not focus on Christianity but is religious in nature, is Henry Hart Milman’s History of the Jews, which, as the title suggests, covers the history of Judaism and its followers. The work, said to present Jewish people as an Oriental tribe, is noted for its objective depictions. Alongside its history, it also includes several studies, including one which focuses on conflicts between Christian and Jews.

First published in 1830, the text followed the history of the Jews, presenting the community more as a nation than a religion. Contemporaries were shocked by the portrayal of Jews as an Oriental people, and it upset many orthodox Christians, including theologian Rev. John Henry Newman, because its objective manner minimized the miraculous events of the Bible. The text was well received, however, by the Gentleman’s Magazine and, more significantly, the Jewish community. Milman continued to write religious histories subsequent to the publication of The History of the Jews. His publications were sometimes viewed as liberal theology and criticized by individuals such as Godfrey Faussett and Newman, but despite the criticism and controversy, he continued his attempts to bring Christianity into intellectual circles and maintain a successful career as both a historian and a clergyman.

The particular version of The History of the Jews in the Queen’s College Collection is the third edition, published by John Murray in London in 1863. A tag on inside front cover slightly covered by the rebound spine notes “Edmonds and Remnants, Binders,” indicating that it was bound by the joint bookbinding business of Jacob Edmonds and Thomas Remnant. A large bookplate with the words “D. D. FEDERICVS MENZIES A M Collegii Aenei Nasi Oxon QVONDAM SOCIVS F. CC. Cathedralis Christi OXONII CANONICVS HONORARIVS” indicates the book’s past ownership by Frederick Menzies.

As far as historical texts are concerned, James Anthony Froude’s History of England is a large donation of Menzies, totaling twelve volumes. These texts, published in pairs between 1856 and 1870, detail major historical events of England from the fall of Wolsey to the defeat of the Spanish Armada. In all, the years 1529 to 1588 are covered in Froude’s volumes. One of his motivations for creating The History of England was to warn his readers that the danger posed by Catholics during the Reformation could resurface via the Anglo-Catholic revival that England was experiencing in the nineteenth century. This work is said to have significantly affected the trajectory of Tudor studies due to its narrative style and Froude’s condemnation of the overly scientific approach to history practiced by most scholars.

Froude specialized in Reformation and Tudor studies. It was his belief that the Protestant Reformation of England in the sixteenth century allowed the country to progress and modernize. According to some critics, he portrayed historical events in a dramatic fashion. He openly opposed the idea of considering history through a scientific lens; some even compared his work to historical romance. Some scholarly individuals disliked his work for this reason, but others enjoyed his vivid narrative style. Some did not acknowledge his work until it reached a certain point of history—The Quarterly Review, for example, did not acknowledge his work until the first volumes on Queen Elizabeth I had been published.

The twelve volumes of The History of England in the Queen’s College Collection come from two different publishers: the first six were published by Parker; the latter, by Longman (also called Longmans or Longmans and Co.). Both publishers were located in London. The volumes appear to be first editions. Volume 7 bears a tag on its back cover: “Bound by Westleys & Co, London.” Volumes 7 to 12 are subtitled Reign of Elizabeth. Bookplates inside each volume state “D. D. FREDERICVS MENZIES A M Colegii Aenei Nasi OXONII QVONDAM SOCIVS F. CC. CATHEDRALIS Christi OXONII CANONICVS HONORARIVS MCMI,” indicating past ownership by Frederick Menzies.

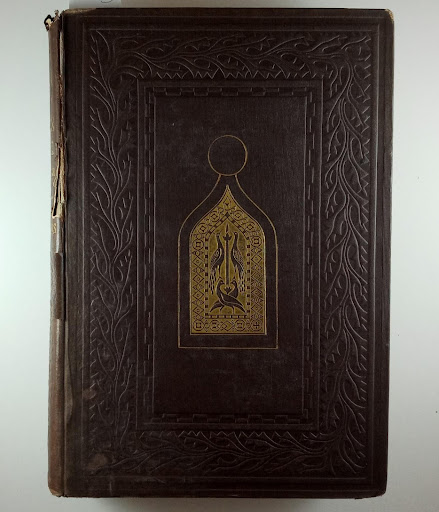

Branching into a different topic but maintaining a historical component, John Ruskin’s The Stones of Venice, also donated by Menzies, is a three-volume treatise and overview of Venetian architecture. First published between 1851 and 1853, the volumes, titled The Foundations, The Sea Stories, and The Fall, focus on the Byzantine, Gothic, and Renaissance eras of architecture respectively. Ruskin expresses how the rise and fall of these architectural eras correlate with the rise and fall of Venice. The Stones of Venice support the ideas that he presented in “The Seven Lamps of Architecture,” an essay written during the European revolutions of 1848 in which he detailed seven moral principles of architecture, which he called lamps.

The Stones of Venice was the result of the most intense period of study of Ruskin’s life and included two long winters in Venice. In The Foundations, Ruskin offers a brief history of Venice in the first chapter, “The Quarry”; however, he does not focus as much on the city throughout the rest of the text. In this volume, he specifies the rules of architecture as well as its functional and ornamental characteristics. He makes comparisons to his previous work, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, and discusses what does and does not adhere to the principles in it. The Sea Stories (a reference to the lowest floors of Venetian buildings, literally called “sea stories”) focuses more on specifically Venetian architecture than the first volume, particularly on Byzantine and Gothic architecture. He discusses certain architectural structures, especially arches, in great detail (although this focus lessens in the third volume). The Fall focuses on Renaissance architecture: the Renaissance brought about the downfall of Venetian architecture, especially in the case of the Grotesque Renaissance. Ruskin later intended to revise The Stones of Venice and possibly add a fourth volume, but this never came to fruition.

These three volumes comprise the second edition of The Stones of Venice. They were printed by Smith, Elder and Co. in London and bound by Westleys & Co. London in 1858. The bookplate states: “D. D. FREDERICVS MENZIES A M Colegii Aenei Nasi Oxoxn QVONDAM SOCIVS F. CC. CATHEDRALIS Christi OXONII CANONICVS HONORARIVS MCMI.” Handwriting on the inside cover, “F. M. Oct 15. 1858,” suggests that this is the date Frederick Menzies came into possession of these volumes, shortly after the second edition was published.

Considering these few texts alone, it can be seen that while many of Menzies’s donations are theological, many focus on history and other areas of studies. In many instances, texts are situated in theology as well as in history or another subject of concern.