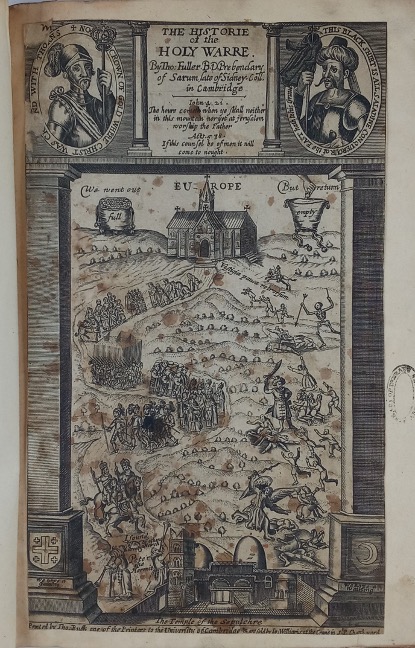

Dr. Bray’s Associates’ Donations to Queen’s College Library

Thomas Bray was born to farmer Richard Bray and his wife, Mary, in Marton, Shropshire, England, in 1656 or 1658. In his early years, he attended Oswestry grammar school before moving on to All Souls’ College, Oxford in 1675, where he was probably a servitor for the school’s fellows. He received his BA in 1678 (as he could not afford the school’s fees, he received his MA from Hart Hall in 1693). After graduating with his BA, Bray worked as a schoolmaster until he was ordained a deacon by the Church of England at the age of 23 in 1681. A year later, he was ordained a priest by Thomas Wood, bishop of Coventry and Lichfield. He became curate of a parish near Bridgnorth in Shropshire until 1682, when rector Sir Thomas Price secured him the position of the Price family chaplain (as well as the living of Lea Marston). His preaching was heard by Lord Simon Digby. Digby praised Bray to his brother William, who presented Bray to the rectory of Over Whitacre in 1685; and so he held the two adjacent Warwickshire positions. In 1690, Lord Digby appointed Bray to the parish of Sheldon, Warwickshire.

Reverend Thomas Bray was an English clergyman whose life’s goal was to spread knowledge and literacy, in- and outside the church. In his later years, he created the organization Dr. Bray’s Associates, which became known as the Associates of the Late Rev. Dr. Bray after his death. The purpose of this group initially was to continue his work of establishing libraries and supporting Black schools. Shortly before his death, he declared the Associates a charitable organization.

In 1695, following Archbishop Thomas Tenison issuing of an injunction calling for regular catechizing of the youth, Bray began writing the first volume of his Catechetical Lectures, which was meant to assist clergy in explaining the catechism to their congregations. Bray’s success as a cleric was noticed by Henry Compton, the Bishop of London. Compton was diocesan of all the colonies, and in 1696 he chose Bray to be commissary of the Anglican Church of Maryland. Bishop William Nicolson approved Bray’s appointment and requested that he obtain both his BA and DD. Bray earned these degrees at Magdalen College (from which he graduated on 17 December 1696), although he struggled to pay the fees and received no financial aid.

Unable to go to Maryland immediately, Bray first appointed other clergymen to go in his stead, but he was concerned about the inaccessibility of books for poorer clerics. These men could not afford to buy good books or build libraries, and Bray believed that this lack of accessibility would be detrimental to their education as well as to their attempts at teaching others the ways of the Anglican church. Thus, Bray set a goal to build parochial libraries in Maryland and the other colonies, a vision he pursued until his death. In December 1695, he printed Proposals for Encouraging Learning and Religion in the Foreign Plantations in which he advocated for libraries for overseas clergy. His first American library resulted from Princess Anne’s financial aid; he founded the Annapolitan Library in Annapolis, Maryland, in her honour. In 1697, he published An essay towards promoting all necessary and useful knowledge, both divine and human, in all parts of his majesty’s dominions, both at home and abroad, a text containing lists of recommended books through which he aimed to extend the libraries to the Church of England. He finally travelled to Maryland in 1699.

Bray’s establishing of libraries in America and England led to the creation of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, or SPCK, which he and four lay friends founded on 8 March 1699. Its purpose was spread Christian education at home and abroad through establishing charity schools and libraries, distributing books and pamphlets, and sending missionaries. Bray himself stayed in Maryland from 1699 to 1700, after which he returned to England. His desire to spread knowledge and literacy went beyond the church, however. Bray also longed to make education more readily available for people of colour, especially Black people and Native Americans; this desire led to the founding of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, or SPG, on 16 June 1701. In 1727, he published Missionala, which focused on the conversion of Black people and Native Americans. During his later years, he concerned himself with the conditions of English prisons and the quality of life for inmates. He was rector of St. Botolph-Without, Aldgate, London, from 1706 until the he passed away in 1730. When he became ill in 1723, Bray created the organization Dr. Bray’s Associates, which became known as the Associates of the Late Rev. Dr. Bray following his death. Its purpose was to continue his work of establishing libraries and supporting schools established for Black students. Shortly before his death in London on 15 February 1730, he declared the Associates a charitable organization.

As far as Bray’s personal life is concerned, in 1685, the same year he was presented to the rectory of Over Whitacre, Bray married a woman named Elenor. Little is known about her. They had a son in 1687 and a daughter in 1688. Elenor died in 1689. In 1698, he married Agnes Sayers of Clerkenwell, Middlesex. They had four children, who all died young.

In sources from 1699 and 1700, Bray expresses his concern about the lack of English and Anglican establishments in Newfoundland. The name of his organization, Dr. Bray’s Associates, is found in 151 texts in the Queen’s College Collection in the Queen Elizabeth II Library at Memorial University. Most of Bray’s donations are theological or historical.

One notable text donated by Bray is Thomas Burnet’s The Sacred Theory of the Earth, originally published in two volumes under the name Telluris theoria sacra, the first in 1681, the second in 1689. In it, Burnet offers explanations for the earth’s physical state and features. He discusses the different states of the earth’s being and estimates its future state. He begins with a description of how he believes the earth was created and ends with its final fate. It drew controversy, particularly for its skepticism toward the Bible’s version of Genesis. However, it was not the most controversial work of Bray’s career: a later piece forced him to resign from his courtly position.

Burnet’s Sacred Theory of the Earth begins with an explanation of how the earth was formed: before the flood described in Genesis, the earth was a moist, oily, and fertile oval which was uniform and smooth, resembling a paradise. The flood, Burnet proposes, was the catalyst for the creation of the world as humanity knows it, and the cracking of the earth to release the waters beneath its surface led to the creation of mountains and oceans. The text as a whole is Burnet’s attempt to combine the idealism of the Cambridge Platonists, Scripture, and an explanation of the features of the earth’s surface in order to account for the past and present states of the earth and to predict its future. The four major events of earth history, as he highlighted them, were its origin from chaos, the universal deluge, the universal conflagration, and the consummation of all things—but, according to Burnet, the latter two events had not yet occurred. He proposed that the present era was the age between the deluge and the conflagration and, during this time, the earth’s surface and interior would undergo slow but continual change; therefore, when the time came in the plan of Divine Providence, the earth would be ready and able to burn. The final period, that of the millennium, was the era following the universal conflagration, with a new heaven and a new earth in which the good and blessed will enjoy a life of peace. At the end of the millennium, he suggested, the earth would be changed into a bright star, and thus the culmination of all things predicted in Scripture would be fulfilled.

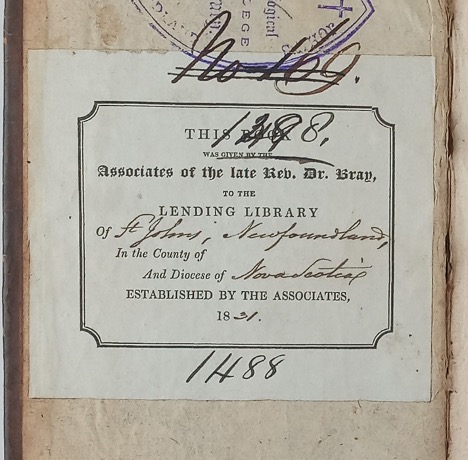

The Queen’s College Collection contains the second volume of Burnet’s Sacred Theory of the Earth published in London by John Hooke in 1726. It is the sixth edition. Its bookplate states: “This book was given by the Associates of the Late Rev. Dr. Bray, to the Lending Library of St. John’s, Newfoundland In the Count of And the Diocese of Nova Scotia Established by the Associates, 1831”; the text, then, was likely donated in 1831. The names “E. R.” and “E. Rouse” are handwritten on the inside of the front cover, indicating past ownership by someone of that name. A page pasted onto the inside back cover contains the words: “Lending Libraries. Rules prescribed by the Associates for the better Preservation of Lending Libraries founded by them.” “St. John’s” is written in as the library location.

Another noteworthy text donated by Bray is Philip Schaff’s History of the Christian Church. The first volume of Schaff’s multi-volume history was published in 1858. In it, Schaff considers the history of the church from the time of Christ until the Reformation and shares his own views on Christianity. He begins with an examination of the preparation for Christianity in Judaism before discussing the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, concluding with an introduction to modern church history and analysis of the Reformation period, including the late 16th-century Protestant movement in Germany and Switzerland.

The first volume of The History of the Christian Church followed and expanded on some of Schaff’s previous works, including What Is Church History? and History of the Apostolic Church. These highlight history and share his own views on Christianity. Schaff praised the church as an institution. He sought to make a readable, accessible history that could be understood by all. He faced criticism for his perspective: he was admonished for being a papist and pro-Catholic. The accessibility of his work also created discord as it meant that it could be applied to everyone, regardless of class, location, or denomination.

All volumes of Schaff’s History of the Christian Church in the Queen’s College Collection are later, revised editions published by T. & T. Clark in Edinburgh between 1885 and 1891. All bear the bookplate “This Book was Given by the Associates of the late Rev. Dr. Bray, to the Clerical Lending Library of Queen’s Collage In the County of Newfoundland Diocese of Aug 1896 19, Delahay Street, S.W.,” thus indicating donation by Bray’s organization. Each volume also has a glued-in page from an external source: “Rules for the Preservation of Dr. Bray’s Lending Libraries in the Colonies.”

The first volume of Joseph Bingham’s Antiquities of the Christian Church is another significant text donated to the Queen’s College Collection by Bray. Bingham’s ten-volume Antiquities of the Christian Church, originally published between 1708 and 1722, serve almost as logical indexes or encyclopedias of Christianity. They are Bingham’s attempt to explain different practices and customs of the Christian church in simpler terms to make them more accessible to readers as well as including hundreds of years of historical information. The first volume of Bingham’s Origines ecclesiasticae, also called The Antiquities of the Christian Church, was published in 1708. Three volumes had been published by 1711. The tenth and final volume was published in 1722. The Antiquities were translated into Latin between 1724 and 1729 by J. H. Grischovius of Halle, and a German abridgement was published in Augsburg between 1788 and 1796. According to L. W. Barnard, through the use of primary sources, the text covers “the hierarchy, ecclesiology, territorial organization, rites, discipline, and calendar of the primitive church” (197). Bingham’s intent was to give a methodical account of the antiquities of the Christian church by reducing the ancient customs, usages, and practices of the church under proper heads so that the reader could easily search the text to read about any specific Christian practices spanning four or five centuries.

The Queen’s College Collection contains the first volume of Bingham’s Antiquities of the Christian Church. This is a new edition that was one of two volumes published in London by Reeves and Turner in 1878. A bookplate denotes that “This Book was Given by the Associates of the late Rev. Dr. Bray, to the Clerical Lending Library of Queen’s Collage In the County of Diocese of 1819, Delahay Street, S.W.” A glued-in page states: “Rules for the Preservation of Dr. Bray’s Lending Libraries in the Colonies.”

One further text of note donated to the Queen’s College Collection by Bray is Benjamin Hoadly’s Reasonableness of Conformity to the Church of England. This text, published in 1703, was a response to Presbyterian Edmund Calamy’s 1702 Abridgment of Richard Baxter’s History of His Life. In it, he shares his views on separation and reformation. The text was one of several significant works written by Hoadly. His writings, which often contained views and opinions not shared by the majority of English clergymen, often led to controversy and discord. However, they also helped to solidify his reputation as one of the most noteworthy clergymen of his time.

The Reasonableness of Conformity to the Church of England was a response to the defense of dissenting separation by the Presbyterian Edmund Calamy in his 1702 Abridgment of Richard Baxter’s History of His Life. Hoadly’s position was based on low-church principles and the work was aimed at the moderate nonconformists who supported the ideal of a national church. Hoadly argued that it was unproductive to separate from an imperfect church to press further Reformation but admitted that the Church of England constitution was flawed; he desired some reform himself. Most crucially, he provided a strong defense of the church on one of the more prevalent issues raised by the Presbyterians: the governing of the church by the bishops. He denied that episcopacy was divine law and stated that, therefore, it was unessential to the church. However, he did argue that the practice was of apostolical origin, supported by tradition, and that it was binding on the church unless “imitation is unpracticable” (Works, 477). Thus, he did not condemn foreign reformed churches and, unlike most high churchmen, recognized the validity of Presbyterian ordination during the interregnum.

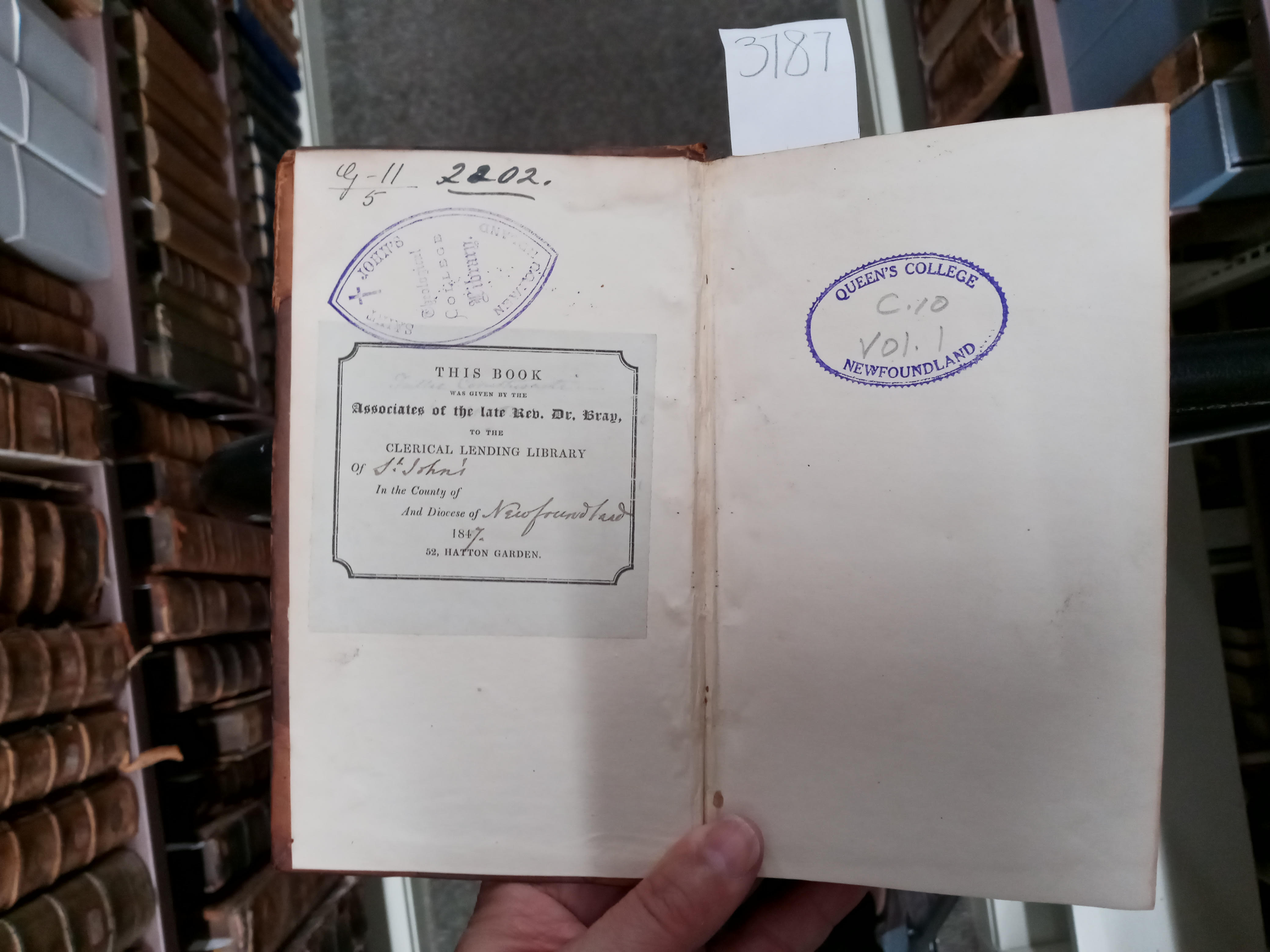

The Reasonableness of Conformity to the Church of England in the Queen’s College Collection is the third edition, published by James Knapton in London in 1712. Its bookplate, “This Book Was Given by the Associates of the late Rev. Dr. Bray, to the Lending Library of St. John’s In the County of And Diocese of Newfoundland 1847 52, Hatton Garden,” indicates a date and location of the original donation. Handwriting on inside front cover states “Ja: Birdges 1736,” and a page pasted onto the inside back cover, “Rules for the Preservation of Dr. Bray’s Lending Libraries.”

These four texts pertain to similar subjects and yet still differ enough from each other to be significant alone. They are representative of the many other theological and/or historical donations from Bray in the Queen’s College Collection.