Basilica Museum-Mullock Library

In the nineteenth century, one St. John’s tradition encouraged leading citizens of the town to host a New Year’s Day levee, a reception held early in the afternoon of New Year’s Day, typically at the residence of its host. One prominent citizen expected to host a levee was the Roman Catholic bishop. Those attending, dressed in their finest, would, upon arrival, stand in line to sign a guest book and be introduced to the bishop. The introduction was followed by refreshments. On a New Year’s Day in 1859 Bishop John Thomas Mullock, the Roman Catholic bishop of St. John’s, hosted his New Year’s levee in the newly established Mullock Library. Among the invited guests was Lieutenant Colonel Robert B. McCrea, a battery commander and later garrison commander at Fort Townshend (now the site of The Rooms).

Impressed by the levee and the newly established library, McCrea, in a book about his experiences in Newfoundland, Lost amid the Fogs: Sketches of Life in Newfoundland, England’s Ancient Colony, remembered this about the levee: “Then to His Lordship [Mullock] we paid our respects and congratulations as was right and proper. A hearty reciprocation and a glass of champagne were his return for the compliments, to say nothing of taking us around his noble library, the finest room in the Colony.” McCrea was not so impressed by the living quarters of the bishop and the priests. “Th[e] reception room was handsome, adorned with statuary from Italy,” he noted, “but for himself and the priests that lived with him, the little room below with its deal chairs and common delf would have been probably scorned by a layman. So strange is the contrast which presents in the attributes of his daily life and the profession he upholds.” Mullock, who died in 1869, the year McCrea’s book was published, would have been pleased with the description of his living quarters—“fitted only for the residence of a plain, simple gentleman”—as reflecting his priestly vow of poverty. Mullock was, however, anything but “plain [and] simple”; he may have been indifferent to the aesthetics of his own residence, but he spared nothing when it came to his Mullock Library.

When Mullock had arrived in St. John’s in 1848, his first task was to help in rebuilding the city. The Great Fire of 1846 had destroyed everything that Bishop Fleming, Mullock’s predecessor, possessed. “[T]he destruction,” Fleming wrote, “involved that of everything of any value that I personally possessed, all my furniture, my books and other valuables, and what to me was scarcely less valuable than all of these, my papers, including my own manuscripts and correspondence as well as numberless Deeds, Grants, etc.” Mullock’s first task, then, after his arrival, was the completion of the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist (the Basilica of St. John the Baptist since 1955), which had been under construction for fourteen years. Once the cathedral was completed, he turned his attention to other ambitious building projects.

In a February 22, 1857, Pastoral Letter, Mullock eloquently expressed what he considered to be the church’s mandate: “[The Church] is the nurse of genius, the mother of the arts and literature: wherever she planted the cross, convents, schools and colleges sprung up; splendid temples adorned the land, the marble breathed and the canvas glowed with the images of Christ and his Saints: and the majestic ceremonies of the Church, the music and poetry and splendor of the Catholic Ritual refined and elevated the souls of her children above the earth ...” And so, after completion of the cathedral, he next envisioned a college, which became St. Bonaventure’s College. With both cathedral and college a reality, his next enterprise was to establish a library.

The idea of a library was raised at the 51st anniversary meeting of the Benevolent Irish Society (BIS) on February 17, 1857. The chairman, Walter Dillon, addressed the patron of the society, Bishop Mullock: “We think nothing would be more calculated to improve the moral and social conditions of the growing youth of the country, than giving them a table for reading and inducing habits of thought and reflection that must greatly affect the character.” This BIS proposal fit perfectly with Mullock’s plans. At this time, there was only one other large library in St. John’s, the St. John’s Library and Reading Room, established in 1820 “with a view [to] rendering accessible to the public generally at a moderate subscription the standard literature of the United Kingdom and the United States,” according to its president. In 1857 this Library boasted that “[i]t has 2700 hundred volumes on its shelves and in the Reading Room.”

The Mullock Library

In December 1859, Mullock informed the Newfoundland House of Assembly that he was undertaking the construction of another important library: “I may mention that the library now in the course of erection will be a room of 79 feet by 30, and 30 feet high. The 10 windows will be of stained glass, and it will be partially a Library for the use of the Public as well as the College. I have a collection already of over 2500 volumes as the nucleus of the Public Library, and many of these books are rare and valuable ... [T]he great benefit of the Institution will not be apparent for several years when the generation now obtaining a high education will become active members of Society” (John Thomas Mullock, Journal of the House of Assembly Appendix, Education, 31 December 1859).

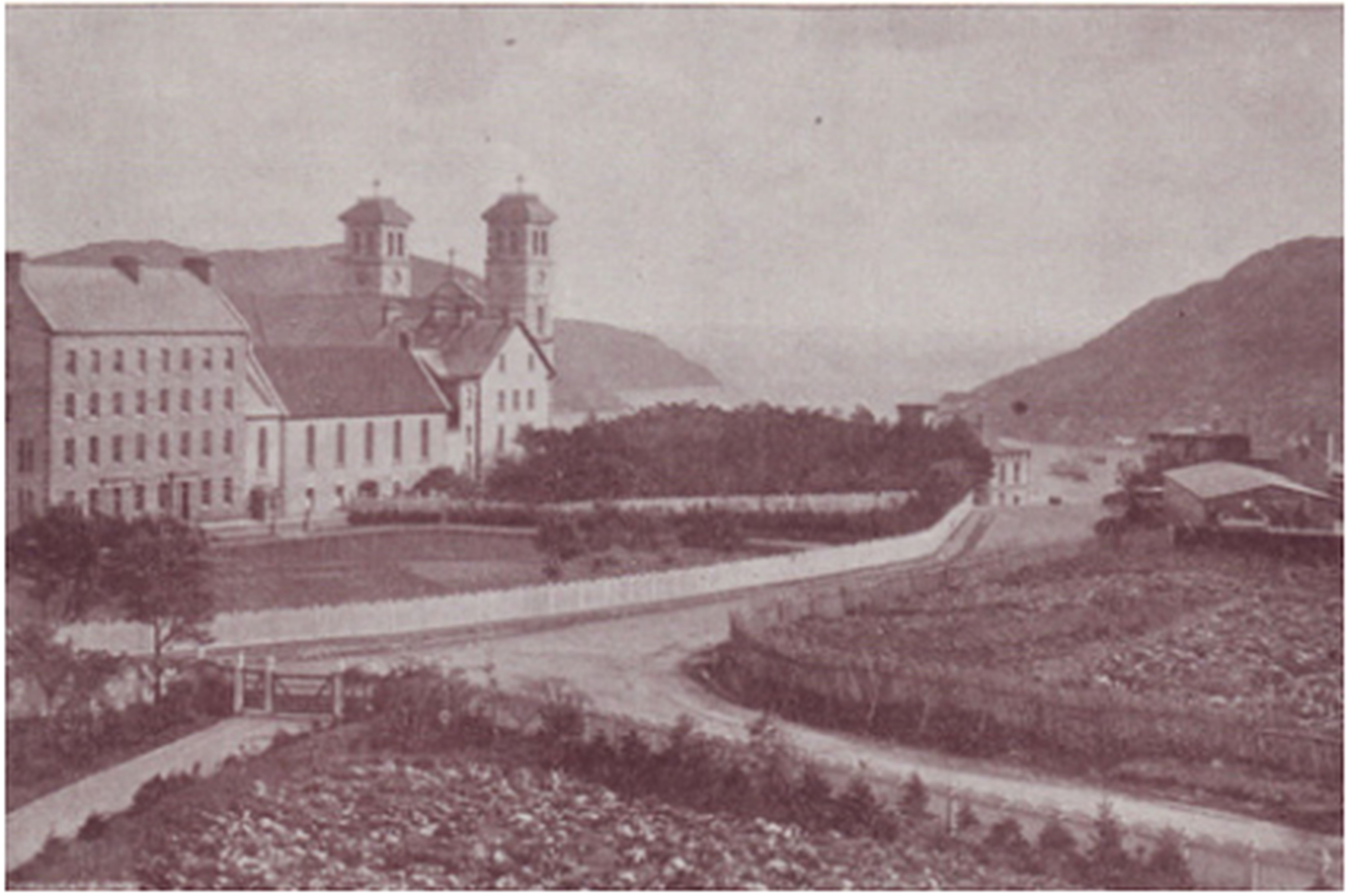

As with all the building projects Mullock had undertaken, he was determined that his “Public Library” would also be a significant architectural and educational edifice. Located on the grounds of the cathedral, it stood strategically between the “Palace” (the traditional name of the bishops’ residence) and the newly built St. Bonaventure’s College. In his February 23, 1857, Pastoral Letter, Mullock had dared to dream that, as the population of St. John’s grew, “without interfering with the plan,” St. Bonaventure’s College could be enlarged, “if necessary[,] even to the dimensions of a University ...” His proposed library would be part of this university.

The construction of this Mullock Library is not well documented, but the land on which it would sit was part of an original land deed given to Bishop Fleming in 1838 for the cathedral. The library would be a two-story saddle-roof construction with a separate entranceway a few yards from the main entrance to St. Bonaventure’s. Only a few shreds of evidence remain of costs; these are bills that Mullock alludes to in his pastoral letters, in which he suggests that initially he had invested “some £1,000 in the construction.” In a 1860 Pastoral Letter, he appealed to the generosity of the Roman Catholic population; he “need[ed] about £1500 more to finish the Library and other offices required to perfect the college] …” It was a substantial commitment; £2,500 in 1860 had the same buying power as Cdn. $81,082 in 2021.

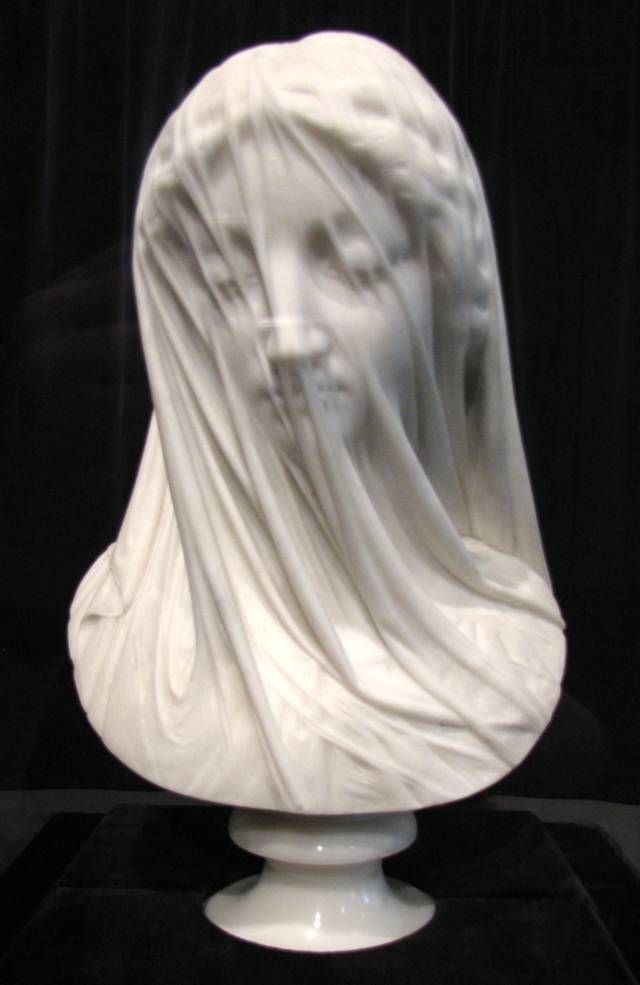

Mullock was keen to embellish the library with the finest art and ornamentation. His December 4, 1856, diary entry stated: “Received safely from Rome, a beautiful statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary in marble, by Strazza. The face is veiled, and the figure and features are all seen. It is a perfect gem of art.” This statue, executed in flawless Carrera marble by the renowned Italian sculptor Giovanni Strazza (1818–75) in Rome, his second of a veiled woman, was described in The Newfoundlander the same day as its arrival. The writer attempts to convey its perfection: “To say that this representation surpasses in perfection of art, any piece of sculpture we have ever seen, conveys but weakly our impression of its exquisite beauty. The possibility of such a triumph of the chisel had not before entered into our conception. Ordinary language must ever fail to do justice to a subject like this—to the rare artistic skill, and to the emotions it produces in the beholder.” The Veiled Virgin was displayed in the Mullock Library until 1862, when Mullock presented it to the superior of Presentation Convent. His sister, Sister Mary Magdalen de Pazzi Mullock, was a professed member of that community, and later its superior.

As for those who designed and constructed the structure that held such works of art, the archives are silent. Likely the same men involved in the construction of the cathedral and St. Bonaventure’s College also worked on the library. It is almost certain that the Conways, a family of masons from Waterford, Ireland, brought over to work on the cathedral, were among them. The ornate plaster ceiling appears to be the work of the Conways; their name has become synonymous with the fine artisanship in all the buildings of the Basilica complex. But perhaps the most personal element connected with the Mullock Library are the bookcases, which currently house the Mullock collection; these were built by Mullock’s father, Thomas.

A Library for Public Use

In 1859 when he proposed his library, Mullock specified that “it w[ould] be partially a Library for the use of the Public as well as the College.” By 1863, however, a shift had occurred in his thinking. On May 1, 1863, Mullock recorded in his diary that he had attended a meeting called by Reverend Richard V. Howley in the Orphan Asylum (School) for the formation of a Catholic Literary Institute. This institute was to be formally established as the St. John’s Catholic Institute (later the St. Joseph’s Catholic Institute) with a constitution that called for “[t]he Librarian [to] have charge of and superintend the Reading Room and Library.” The librarian was to “keep a list of the Books and Periodicals belonging to the Institute, and of the names of the members to whom they may be lent, stating the name of the book, the time it was given out, and the date of its return; and he shall at each quarterly meeting report to the Institute the condition of the Library and Reading Room ...” In April 1866, Mullock approved a Memorandum of Agreement between Daniel Henderson and Howley, the institute’s president—to take the rooms and apartments which formed the second floor of the building situated on Duckworth Street opposite the Exchange Building, also known as “The Temple,” as a home for the institute. This building remained the home of the Catholic Institute with its public library until the Great Fire of 1892.

Mullock’s books may have been limited in the early days to use by the clergy and the students of St. Bonaventure’s College, but the library itself continued to be used extensively by Catholic organizations for formal and informal gatherings. Given that the number of individuals attending a function in the Mullock Library could range from 400 to 900, as it was on March 3, such gatherings were not only an invitation for structural failure but also not a venue for the claustrophobic. On March 3, 1878, members of the Star of the Sea Association of St. John’s gathered at the Cathedral to celebrate the seventh anniversary of the association’s founding in 1871. The celebrations began with a High Mass at 11 a.m., included Vespers later that day led by Father Ryan, and concluded with a “resplendent dinner.” By evening, Bishop Thomas J. Power recorded in his diary that a disaster had been averted that day: “The members of the Star of the Sea came to the Library after the High Mass. There were about 900 assembled. All did not get in the room.” After Power had given a brief speech, he “retired from the library,” and shortly thereafter, “a beam supporting the floor cracked—there was some confusion and great fear for awhile. It might have been a serious matter. It could have been a deplorable calamity but thank God that all escaped.” The following day Power “did Mass in thanksgiving to God for the almost miraculous escape of the many individuals in the Library yesterday.”

Other events took place with less threat to life and limb. On July 13, 1881, the Evening Telegram reported that for the St. Bonaventure’s College closing exercises, for the session ending July 12, 1881, the Mullock Library “was fitted up … with stage, curtains and scenes. His Lordship the Bishop presided. All the clergymen of the city and many from surrounding districts honored the occasion. The members of the boards of education and the parents and guardians of the pupils mustered in numbers so that the spacious Hall was filled with an audience of no less than four hundred.” By the 1880s it was becoming clear that official receptions would have to be moved to the cathedral. This issue was highlighted by the Evening Telegram on January 3, 1887, when it reported that the Total Abstinence Society “entered the Cathedral to pay the usual congratulations to the Most Rev. Dr. Power and the Clergy, the numbers of the body having outgrown the accommodation of the Mullock Library, where they were wont to pay their New Year’s call in former days.”

Some organizations may have outgrown the Mullock Library, but it was still the venue of choice for the bishops for private events. It was where most priests upon ordination gathered with their friends and family, and it was where a bishop met with his clergy for formal functions as well as informal gatherings. For example, the February 2, 1881, issue of the Evening Telegram reported that “[t]his evening the clergy will be entertained at dinner … and will afterwards be present at a performance of the operetta, Lily Bell, in the Mullock Library.” Bishops were also keen to make the Mullock Library available to Catholic organizations. The February 11, 1892, Evening Telegram announced that “His Lordship Most Reverend Dr. Power has very kindly placed the Mullock Library apartment at the disposal of the Mercy Covent ladies, to have therein during the winter months wholesome and instructive entertainments for the raising of funds for the Mercy Convent Chapel.” The library would have also been available to two other religious communities—the Congregation of the Sisters of the Presentation and the Congregation of Christian Brothers.

In 1892, other Catholic organizations were looking for access to the Mullock Library. As the sun rose on July 9, 1892, more than two-thirds of St. John’s lay in ruins and approximately 12,000 people had been dispossessed, having lost everything except the clothes they were wearing. In just twelve hours, the Great Fire had claimed the lives of three people and caused $13 million in property damage. Among those properties that were razed were the clubrooms of many Catholic societies and associations—Catechism League of the Sacred Heart and Holy Name Societies, the Total Abstinence Society, and the Ladies of St. Vincent de Paul were among those institutions looking for a new home.

In the 1890s, under the leadership of Archbishop Michael Francis Howley (1895–1914), the Mullock Library doors were flung open, not only as a place of meeting for Catholic organizations and societies but also as a place of entertainment. Local papers reported almost daily on some function or event being held in the historic library. One of the first honoured the installation of Howley as bishop of St. John’s, which the Evening Telegram described on February 27, 1895: “The Star of the Sea Association assembled at their ball, 400 strong, and marched in torchlight procession to the Mullock Library, to offer an address of welcome to His Lordship Bishop Howley. It was a splendid demonstration. No finer night could be witnessed than that strong brigade of stalwart men; His Lordship entered the Library, the band playing appropriate music.” The Episcopal Library was also a hub of activity for students at St. Bonaventure’s College: it served as an examination room, hosted senior debates, and was the site of announcements of prizes, whether scholarships or athletic trophies, and of the Annual Exhibition of Pupils.