The 1918 Spanish Flu

The Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918-19 killed between 20 and 40 million people worldwide, making it one of the largest and most destructive outbreaks of infectious disease in recorded history. It first appeared in Newfoundland and Labrador in September 1918 and killed more than 600 people in less than five months. The effects were most devastating in Labrador, where the disease killed close to one third of the Inuit population and forced some communities out of existence. Death rates were particularly high in the Inuit villages of Okak and Hebron.

Despite its name, the Spanish influenza appeared in the United States, China, and France before moving on to Spain and the rest of the world in the spring of 1918. However, the disease received more press coverage in Spain than elsewhere and it is partly for this reason that it became known as the Spanish influenza. The highly contagious nature of the virus allowed it to spread rapidly from one continent to another as hundreds of thousands of troops traveled around the world during the final months of World War One.

Pandemic Reaches Newfoundland

The pandemic reached Newfoundland on 30 September 1918 when a steamer carrying three infected crewmen docked at St. John’s harbour. Three more infected sailors arrived at Burin on October 4 and they travelled by rail to St. John’s for treatment. A doctor diagnosed the city’s first two local cases of influenza the following day and sent both people to a hospital. Within two weeks, newspapers reported that several hundred people were infected in St. John’s.

By mid-October, Medical Officer of Health N.S. Fraser had closed the city’s schools, theatres, concert halls, and other public buildings to help prevent the virus from spreading. The government converted the King George V Seamen’s Institute on Water Street into a temporary 32-bed hospital, but because many of the country’s medical personnel were serving overseas with the military, there was a severe shortage of nurses. On October 17, the Public Health Division published appeals for nurses and volunteers in local newspapers.

Doctors and nurses who were available spent long hours treating infected patients, often becoming ill themselves. This was the case with volunteer nurse Ethel Dickinson, who contracted the Spanish flu on 24 October 1918 while working at the King George V Seamen’s Institute. After two days of sickness, Dickinson died on October 26 and was buried the same day. Today, a monument in her honour stands in downtown St. John’s.

By early December, 62 people had died from Spanish influenza in St. John’s, but no new cases were appearing. The situation was considerably worse in the outports, where fewer medical facilities and practitioners existed to combat the disease. On October 19, the Daily News reported that “The prevailing epidemic is particularly severe on the West Coast. We understand that around Bay of Islands there have been several deaths, and there are over a hundred cases reported now under treatment.”

The situation continued to deteriorate in the coming weeks and months. In the last week of November, 1,586 cases of influenza and 44 deaths were reported in 28 communities across the island. The highest incidences occurred in St. Mary’s Bay and Round Harbour, which reported 628 and 450 cases, respectively. By February 1919, the epidemic had largely ended on the island, although traces of it remained until the summer. Before it disappeared, the disease killed 170 people in outport Newfoundland.

The Spanish Flu in Labrador

The Spanish influenza was even more destructive in Labrador, which experienced a disproportionately high mortality rate; the same virus that killed less than one per cent of Newfoundland’s population killed 10 per cent of Labrador’s. Several factors contributed to this – Labrador did not possess adequate medical resources and personnel to prevent the disease from spreading, frequent storms prevented doctors and nurses from travelling to Labrador’s remote communities, and inefficient modes of communication with the outside world made it difficult to request help from Newfoundland.

The virus first appeared at Cartwright after the mail boat SS Sagona docked there on October 20 with four infected crewmembers. Two days later, most of the community’s residents were sick and the disease was spreading throughout Sandwich Bay. By early 1919, the influenza had killed 69 of the area’s 300 residents.

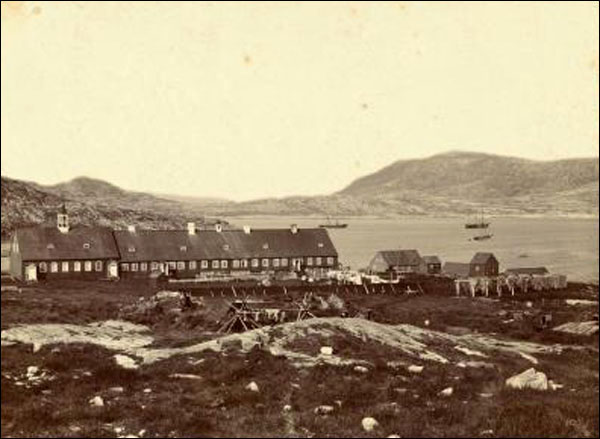

The same day that the Sagona arrived at Cartwright, the supply ship SS Harmony departed St. John’s harbour for the northern Labrador community of Hebron. Although the influenza had by then reached epidemic proportions in St. John’s, the government placed few restrictions on shipping arriving at or departing from the city’s harbour. When the Harmony arrived at Hebron on October 27, at least one infected crewmember was on board. The virus quickly spread throughout the village, killing entire families and leaving dozens of children orphaned. By November 19, 86 of Hebron’s 100 residents were dead. A further 74 people died in surrounding communities, cutting the area’s population to 70 from 220.

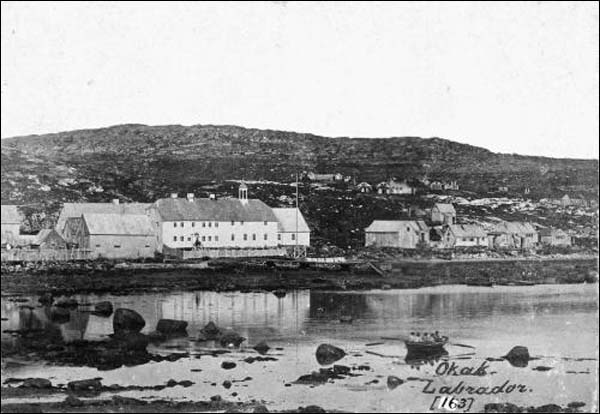

Unaware of the situation at Hebron, the Harmony’s captain continued south to Okak, where he arrived on November 4. Within hours of the ship’s departure on November 8, many people in the village began showing signs of illness. Two weeks later, 70 Okak residents were dead and the disease had spread to nearby hunting camps. At Sillutalik (Cutthroat), the flu killed 40 of 45 residents, while 13 of 18 people died at Orlik. Seven-year-old Martha Joshua survived alone for five weeks in Uivaq before a search party from Okak found her in early January. After the influenza killed her entire family, Joshua survived alone by eating hard bread and melting snow for drinking water.

By the end of December, the virus had decimated Okak, killing 204 of its 263 residents. It was a nightmarish situation. The frozen ground made it impossible to bury the dead in a timely fashion and residents piled corpses in a few vacant houses. Soon, the dead outnumbered the living and it was the few remaining survivors who shared a handful of houses. Making matters worse, dozens of sled dogs grew wild with hunger and began eating the corpses or attacking sick humans. Survivors had to shoot them on sight.

Aftermath

As the virus disappeared from Labrador in late December and early January, survivors began to bury their dead. Residents at Hebron cut holes in the ice, weighted the bodies with rocks, and placed the dead in the water. At Okak, residents poured petroleum into the ground and made a large fire to thaw the soil. By January 7, all of the dead had been lowered into a mass grave measuring 32 feet long and 8 feet deep. Survivors then dismantled the community entirely, burning all houses and furniture before moving to Nain, Hopedale, or Hebron. Before the pandemic, Okak was the largest Inuit settlement on Labrador’s coast and one of its most prosperous. By January, the influenza had killed every Inuit adult male at Okak and forced the community out of existence.

Former Okak resident Kitora Boas, who was 20 years old in 1918, described a lingering depression that followed the pandemic: “For a long time after there was this sense of decline as far as yearly activities were concerned among the Inuit and in all northern Labrador communities. A sense of let down was in the air for a long time.” (Them Days 11.3 (1986): 49-52)

Although its effects were both devastating and far-reaching, the influenza spread through Labrador in a matter of weeks, killing more than 30 per cent of the Inuit population and infecting many others. Those who did not die from the disease often experienced heart and respiratory troubles for the rest of their lives.