Surgeons and Criminal Justice

Surgeons were a fixture of the 18th-century fishery. Newfoundland's first Chief Justice, John Reeves, observed that in almost every harbour there was a surgeon or medical man. In a system dating from the seventeenth century, at the start of the fishing season each servant had to enter his or her name on the "doctor's books" of a surgeon, usually chosen by the master, and paid a flat fee (between five and ten shillings) at the end of the summer. Servants who needed special care for injuries or extended illness paid additional charges. Evidence suggests an abundance of medical practitioners in outport communities, such as Trinity, which had at least four active surgeons in the late 18th century. In addition, there were several surgeons and apothecaries attached to the army garrison at St. John's and Placentia, as well as a surgeon on many of the navy vessels stationed at Newfoundland. Like those in Nova Scotia, surgeons attached to the military in Newfoundland could become established members of colonial society. They earned incomes which could surpass £100 for a single fishing season, making them the nearest thing to a professional class on the island.

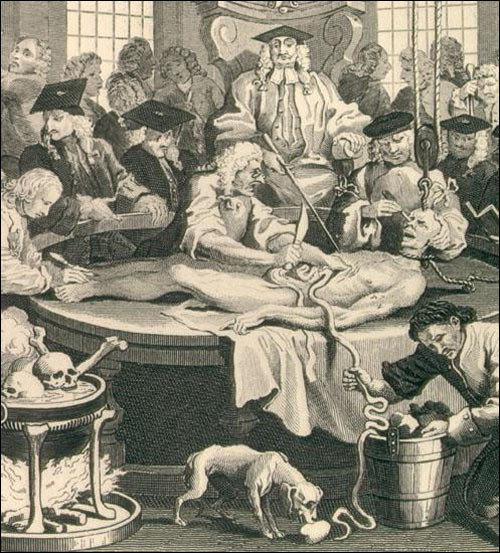

The training and status of surgeons in Newfoundland were comparable to their counterparts in England. By the 1750s surgeons had ended their affiliation with barbers, and Surgeon's Hall in London examined all applicants for naval appointments. Typically, surgeons in Newfoundland, such as James Yonge, apprenticed as surgeons' mates and honed their skills through clinical practice; Yonge also brought books to study while practising at Bay Bulls in 1670. Though many learned their profession in the navy, others, notably John Clinch of Trinity, had worked in England or Ireland before coming to Newfoundland. Clinch had studied in London with the renowned surgeon John Hunter and helped to pioneer the use of vaccines in North America.

With a relatively high degree of competition for patients, surgeons had to exhibit proficiency and to guard their reputations. In 1789, Peter Le Breton, a prominent Conception Bay surgeon, brought a suit for slander before the quarter sessions to refute rumours he had procured a sample of the smallpox virus for inoculation in Harbour Grace. Familiar with both the merchant and working classes, surgeons occupied a solidly respectable position throughout outport communities.

Consequently surgeons were frequently appointed to serve as magistrates in 18th-century Newfoundland. Twelve surgeons can be positively identified as active justices of the peace. Three of the commissioners of oyer and terminer—D'Ewes Coke, Thomas Dodd, and Jonathan Ogden—were also practising surgeons (Coke and Ogden were later appointed chief justices of the Newfoundland Supreme Court). Surgeons possessed three qualities desirable for local magistrates: they were relatively learned, actively willing, and readily available. The British government approved this trend because it viewed surgeons as enjoying greater economic independence than other candidates for office. Not surprisingly, medical and judicial roles intermixed: of the 18 surgeons who gave evidence in murder trials, five were also justices in the districts where the homicides had occurred. In Newfoundland, then, surgeons were likely to be at the heart of local crises, whether as medical practitioner, local magistrate, or both.

In particular, surgeons readily appeared to give evidence in the island's courts. Unlike 18th-century England, there were no reports of surgeons having to be subpoenaed, nor of any payment for their testimony in Newfoundland. In court surgeons voluntarily testified on the cause and severity of servants' injuries and illnesses. At the Placentia quarter sessions in 1770, for example, Joseph McNamara brought a complaint against Joseph Conway, a fellow servant, for wounding him with a hatchet and disabling him for over a month. The court examined John Ryan, the surgeon who had attended McNamara, and then ordered all of Conway's wages to be applied to the medical costs. In other cases surgeons' evidence included circumstances surrounding a patient's treatment; at the 1769 quarter sessions in Trinity, a local surgeon maintained that Jonathan Meany's injuries were simply the result of a drunken quarrel. Given their familiarity with patients and their appointments as justices of the peace, most surgeons in Newfoundland were doubtless aware of personal reputations and the roots of local violence.

Surgeons dominated the process by which violent or suspicious deaths were investigated in Newfoundland. In England the office of coroner generally had fallen into disrepute by the 18th century. Expertise at coroners' inquests was notoriously uneven, although surgeons were occasionally asked to perform post mortem examinations. In 18th-century Newfoundland, coroners' juries acted without surgeons in only two known cases, while surgeons performed autopsies at four coroners' inquests and independently conducted post mortems of five homicides. In another case, at Trinity in 1772, during the funeral of Maurice Power the rector noticed signs of violence on the body and notified D'Ewes Coke, the resident naval surgeon. With no legal authority, Coke conducted a post mortem examination and organized a jury of fourteen men to view the corpse. He later complained that he had to rely on planters and servants because local merchants had refused to serve as jurors; such attitudes undoubtedly contributed to the island's relative dearth of coroners' inquests. Upon receiving a copy of the jury's verdict and Coke's own report, Governor Shuldham commended the surgeon's initiative and quickly appointed him justice of the peace for Trinity.

Most post mortem examinations in Newfoundland, however, were remarkably consistent in both form and content. Typically, within 36 hours of a homicide, three surgeons examined the injured region of the corpse. Their report briefly described the state of affected tissue and vital organs or, in cases of head trauma, the damage of, or depth of penetration into, the cranium. The structure of post mortem reports remained similar to the first known example in 1730:

We the under-named being requested to view the body of Walter Nevell have upon examination found a fracture in the right Os Temporis [temporal bone] of his Cranium which in our opinion is the principal cause of the said Nevell's death.

(Bannister 1998 115)

The post mortem was a specific inquiry, rather than a full autopsy; its purpose simply was to ascertain whether the injuries were the primary cause of death. Neither the probable suspect nor possible weapon was stipulated. Of the eight extant post mortems conducted by surgeons, four were for head trauma, three for abdominal injuries, and the other for unspecified wounds. Two of the reports concluded that the injuries were insufficient to have caused the victim's death. Yet post mortems marked only the first stage of forensic medicine. In each case surgeons affirmed their conclusions in court, and their testimony formed a crucial part of evidence heard during murder trials.

Between 1750 and 1791 there were 20 trials for murder in Newfoundland, half of which heard evidence from surgeons. The assizes apparently considered surgeons' testimony whenever the exact cause of death was uncertain and a port mortem was possible. In the cases without surgeons' evidence, four of the victims had drowned at sea, three had been shot at close range, and one had died in an unsettled territory. A comparison of verdicts offers a rough indication of the impact of surgeon's testimony: 14 of the 19 defendants in trials with evidence from surgeons were found guilty of murder, whereas only three of the 11 men and women indicted in other cases were similarly judged. The importance of forensic medicine is clearly underscored by the fact that only once did a trial verdict not correspond to the post mortem report given in court. Surgeons' testimony addressed two crucial questions in trials for murder: whether illness or disease suffered by the deceased, before or after a violent assault, was a factor in the homicide; and second, whether injuries from a specific beating were severe enough to be the immediate cause of death. Their roles as medical and legal authorities engendered a legal culture in which they were a vital part of the island's criminal justice system.