Indigenous Peoples and Confederation

When Newfoundland and Labrador joined Canada in 1949, the provincial and federal governments made no special provisions for the new province's Indigenous groups. The Terms of Union, which determined how Newfoundland and Labrador would operate as a province, did not mention Indigenous people nor did it clarify their status within the country. As a result, Innu, Inuit, Mi'kmaq and Southern Inuit people living in Newfoundland and Labrador could not access the same programs, services, and funding the federal Indian Act made available to other Indigenous groups in Canada.

The years after Confederation resulted in confusion about how government policies would apply to Newfoundland and Labrador's Indigenous population, and whether federal or provincial authorities should administer them. It was not until 1954 that Ottawa created a formal plan to help pay for medical and other services in Indigenous communities. The program expanded in the coming years, but still fell short of delivering the same level of funding or variety of services that the federal government provided to Indigenous groups elsewhere in Canada.

By not explicitly defining Ottawa's constitutional and financial responsibilities toward Newfoundland and Labrador's Indigenous population, the Terms of Union created lingering tensions between Indigenous groups and government officials, as well as between federal and provincial authorities. Indigenous leaders in the province feel the omission has hampered their efforts to preserve their culture, settle land claims, and obtain self-government, while confusion has existed between provincial and federal officials over which level of government should be responsible for administering Indigenous affairs.

The Terms of Union

Newfoundland and Labrador signed a memorandum of agreement with Canada on 11 December 1948 outlining how the new province would operate as a part of the country. Known as the Terms of Union, it determined which laws and responsibilities would fall under provincial jurisdiction and which would remain under federal control. The agreement covered a wide range of areas, including fiscal management, education, health care, resource rights, sovereignty, law enforcement, defence, unemployment benefits, old-age pensions, transportation, and even the manufacture of margarine.

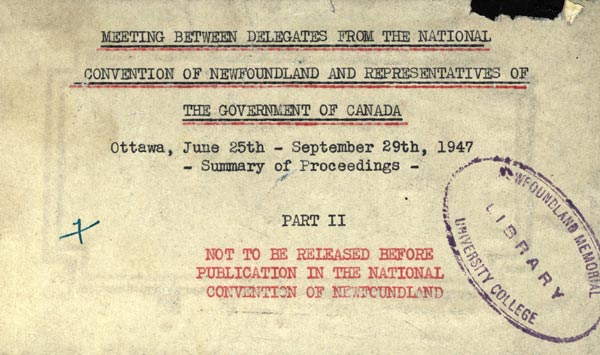

Negotiations towards the terms began on 25 June 1947, when elected representatives from Newfoundland and Labrador met with federal officials in Ottawa, and involved a series of talks over the following year. During this time, delegates discussed potential new policies aimed at Newfoundland and Labrador Indigenous peoples. Representatives from both sides initially felt the federal government should be responsible for the direct administration of Indigenous peoples, as it was in other provinces and territories. Prior to Confederation, the Newfoundland and Labrador government had no special agencies or departments to work with the Indigenous population, nor had it developed any land claim or other agreements.

An October 1947 publication entitled Meetings between Delegates from the National Convention of Newfoundland and Representatives of the Government of Canada stated that: “In the event of Newfoundland becoming a province of Canada the Indians and Eskimos of Newfoundland and Labrador would be the sole responsibility of the federal government” (vol. 2, p.102). The document set out a variety of benefits and regulations that would affect Indigenous groups in Newfoundland and Labrador, including free education and medical services, family allowances “paid on the same basis as white population,” land reserves, and the exemption of Indigenous peoples Ù “from land tax and tax on income earned on the reserve.”

However, the document also stated that no Indigenous person would be allowed to vote unless he or she abandoned Indigenous status and gave up entitlement to benefits under the federal Indian Act. Unlike elsewhere in Canada, Indigenous groups in Newfoundland and Labrador were able to vote. By September 1948, Canadian officials with the Indian Affairs Branch questioned whether negotiators should revise the proposed policies regarding Indigenous groups in Newfoundland and Labrador to prevent them from becoming disenfranchised. Officials suggested either altering the Indian Act to preserve the right to vote or treating Indigenous peoples in the new province as members of the general population. Some authorities wondered if they should extend the Indian Act at all to a population that did not receive any special status or benefits prior to Confederation.

A Newfoundland and Labrador official, Natural Resources Secretary K.J. Carter, helped close the matter in October 1948, when he suggested to Canadian representatives that it would be a “retrograde step” to extend the Indian Act to the new province, in part because it would disenfranchise the Indigenous population. Carter argued the Newfoundland and Labrador government should administer its Indigenous population, with help from federal grant money.

Although opting out of the Indian Act ran counter to federal Indigenous policy, authorities on both sides of the negotiation process accepted Carter's proposal. The reasons officials gave for this decision were that the Indian Act would disenfranchise the Indigenous population; there were no existing reserves in Newfoundland and Labrador, which would make the delivery of services difficult; the new province's Indigenous population was relatively small; and officials claimed many Indigenous people were assimilated into mainstream white society.

Academics have since suggested other reasons which may have contributed to the decision. The federal government may have wanted to avoid the high costs of delivering services to remote areas in Labrador, while the Newfoundland and Labrador government may have worried Indigenous peoples under federal care would receive a higher level of service than their non-Indigenous neighbours, sparking tensions within the province (Tanner 1998; Tompkins 1988). At the same time, a Special Committee of the Senate and House of Commons on the Indian Act recommended the federal government assimilate Indigenous people into mainstream society and remove the status they had under the Indian Act; this new policy thrust may have influenced federal officials' decision to not extend the Indian Act to Newfoundland and Labrador (Hanrahan 2003; Tompkins 1988).

After Confederation

Although delegates on both sides agreed the federal government would provide funds for Newfoundland and Labrador's Indigenous population without directly administering it, the Terms of Union did not set out this arrangement. Instead, the final draft of the agreement made no specific provisions for or reference to the new province's Indigenous population.

The Terms did, however, state indirectly that the Indigenous population fell under federal jurisdiction. Section Three of the Terms affirm “The Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1940 apply to the Province of Newfoundland in the same way, and to the like extent as they apply to the provinces heretofore comprised in Canada.” In turn, the Constitution Act, 1867 states “the exclusive Legislative Authority of the Parliament of Canada extends to all Matters coming within the Classes of Subjects next hereinafter enumerated; that is to say … Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians.”

But the federal government did not exercise its jurisdiction in Newfoundland and Labrador and instead followed the arrangement agreed upon in negotiations leading up to the signing of the Terms. Without any specific rules outlining the relationship between the federal and provincial governments, as well as between government officials and Indigenous groups, the payment and administration of funds were sporadic and often ineffectual in the early years of Confederation.

In 1954, the province reached a formal agreement with federal authorities that Ottawa would help pay for health-care, education, and welfare services for Labrador's Innu and Inuit populations, while the province would distribute funds. Government bureaucrats expanded the agreement over the next 30 years to include municipal services, education, social services, and economic development, and in 1973 made funding available to Mi'kmaq people living at Conne River. A common complaint, however, was that these monies did not go directly to Indigenous people, but rather to communities the province designated as having large Indigenous populations, such as Sheshatshiu and Nain. This made it impossible for Indigenous people living outside of designated communities to access services paid for by the federal government.

Unlike in other provinces and territories, no bands or reserves existed in Newfoundland and Labrador until the 1980s and its Indigenous peoples could not register under the federal Indian Act. This made their land, resources, and culture vulnerable to outside forces over which they had little to no control. Under the Smallwood government, for example, the Bay d'Espoir and Upper Churchill Falls hydroelectric projects flooded Mi'kmaq and Innu hunting grounds and destroyed Innu burial grounds.

The federal and provincial approaches to administering Newfoundland and Labrador's Indigenous affairs have received criticism from several government and academic reports since Confederation. Foremost among these was the 1974 Report of the Royal Commission on Labrador, which found that Ottawa gave much less funding to Labrador's Indigenous peoples than it did to similar groups in other provinces and territories. It recommended that the benefits of federal funding should go to Indigenous peoples instead of to designated communities, and that Ottawa should make the same programs and services available to the province's Indigenous population that it delivered elsewhere in Canada.

Later Developments

Since Confederation, Indigenous groups within the province have worked hard toward obtaining self-government, settling land claims, and in some cases, gaining recognition under the Indian Act. Although many Indigenous leaders feel the Terms of Union have undermined their efforts, all groups have made significant progress toward reaching their goals in recent decades.

After years of negotiations, the Conne River Mi'kmaq became Newfoundland and Labrador's first Indigenous people to register under the Act in 1984; three years later, Ottawa also recognized Conne River as a status Indian Reserve. In 2008, the roughly 7,800 Mi'kmaq not a part of Conne River accepted an agreement-in-principle with the federal government to form a landless band under the Indian Act.

The Inuit people of Labrador won the right to self-government in 2004 after settling a land claim agreement with the federal and provincial governments. The claim was the final one to cover Inuit in Canada and was the culmination of more than 15 years of negotiations. On 1 December 2005, Inuit in Labrador became a self-governing people and formed the Nunatsiavut Government.

In 2002, the Innu Nation and two Band Councils succeeded in having the federal government register the Labrador Innu as status Indians, giving them access to various federal programs and services for First Nations people in Canada. The government also recognized the communities of Natuashish and Sheshatshiu as reserve lands in 2003 and 2006, respectively. The Innu Nation is currently involved in land claim and self-governance negotiations with the federal and provincial governments.

The Labrador Metis Nation (now the NunatuKavut Community Council) filed a land claim with the federal government in 1991 for land in central and southeastern Labrador. As of 2008, Ottawa had not yet decided if it will accept the claim for negotiation.