Economic Changes, 1815-1832

The reform era was a time of tremendous economic hardship for Newfoundland and Labrador. The Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815 and plunged the colony into an economic depression that lasted for years. Fish prices dropped, competition increased, merchant firms struggled to stay solvent, and fish workers watched their earnings disappear. A series of harsh winters, failed seal hunts, and fires only compounded the situation for already destitute families. The government tried to create work by developing road building and other programs, but poverty remained widespread until the 1820s.

Diversification into areas outside of the cod fishery eventually helped to stabilize the economy and end the downturn. The seal hunt emerged as an important form of supplementary income for local fishers, while domestic cod fisheries expanded into Labrador's inshore waters. Agriculture also made gains, although on a much smaller scale than the seal hunt. St. John's developed into a commercial and administrative hub with a relatively complex economy; the town not only supported fishers and merchants, but also physicians, shopkeepers, bakers, butchers, shoemakers, watchmakers, tailors, journalists, and other workers.

Before the Downturn

Before Newfoundland and Labrador entered a lengthy depression in 1815, it experienced almost three decades of growing economic prosperity. This was in large part due to temporary social and economic conditions created by the French Revolution (1789-1799), Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), and Anglo-American War (1812-1814), which greatly favoured the colony's resident fish industry.

During hostilities, France, America, and other warring nations withdrew from the fish trade, which gave the island's fishers an almost complete monopoly over the lucrative industry. England also scaled back its involvement with the migratory fishery to avoid enemy attack and to fortify its navy with experienced seamen. At the same time, increased wartime demand for saltfish caused prices to spike on the foreign market, which resulted in unprecedented profits for local merchants and fishers. The colony's suddenly booming economy attracted large numbers of immigrants from the British Isles hoping to find employment and avoid enlistment into European military forces.

Newfoundland and Labrador's saltfish exports increased from 625,519 quintals in 1805 to 1,182,661 in 1815, while its permanent population almost doubled during the same time period, jumping from 21,975 residents to 40,568. Merchants and planters earned higher profits than ever before, allowing them to pay fish workers higher wages – local splitters, for example, saw their incomes jump from about £30 per season before the war to as much as £140 in 1814.

Postwar Depression

When hostilities ended in 1815, so too did the international conditions that had granted Newfoundland and Labrador its sudden economic prosperity. Prices for saltfish dropped to prewar levels, while previously warring nations reentered the fish trade and competed for access to cod stocks and important foreign markets. In an effort to rebuild their fisheries and provide an incentive to fishers, France and America issued bounties to workers harvesting cod on the Grand Banks. Newfoundland and Labrador fishers received no such government subsidies and struggled to compete with better funded foreign fleets. Norway also reentered the fish trade following the wars and became a major competitor for Spanish and other markets.

At the same time, many European nations significantly raised import duties on cod and other products once hostilities ended; this included Spain, which was a major market for Newfoundland and Labrador saltfish. The Napoleonic Wars had greatly damaged Spain's economy and its government hoped to generate revenue and boost local industries by raising taxes on imports. The policy, however, hurt business for Newfoundland and Labrador merchants by reducing their profits.

Falling saltfish prices, rising competition, and new import duties significantly reduced the revenue Newfoundland and Labrador earned from its previously booming codfish industry. Dwindling profits forced some merchant firms to close, while others scaled back their operations. As a result, fish workers earned significantly lower wages and unemployment became widespread.

Despite economic hardships, boatloads of migrants continued arriving at the colony. The vast majority were from Ireland, where news of the downturn was largely unknown. Newfoundland and Labrador's economy was no longer able to support a rapidly rising population and new settlers further contributed to rising levels of unemployment and destitution.

A series of harsh winters between 1815 and 1817 made living conditions even worse for residents, while winter fires at St. John's in 1816 and 1817 left thousands homeless. Dangerous ice conditions in the spring of 1817 grounded the island's sealing vessels and eliminated a much-needed source of income for already destitute families. Widespread poverty, hunger, and suffering resulted in public discontent and the looting of some stores. In 1816, for example, Bay Bulls residents raided a vessel carrying bread and flour, while St. John's, Carbonear, and Harbour Grace residents broke into merchants' stores to obtain food and other provisions.

The government tried to provide relief by distributing provisions, creating road-building projects, and promoting agriculture, but was unable to curb growing rates of unemployment and poverty. Further, the cost of maintaining relief programs in addition to performing its regular duties was a heavy financial burden for the government.

Growing Diversification

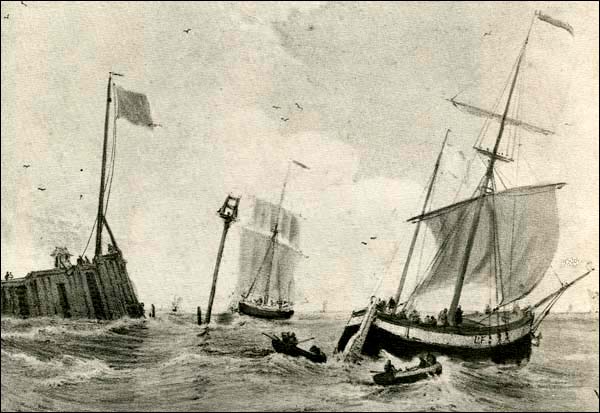

Diversification into industries other than the cod fishery eventually helped to bolster the Newfoundland and Labrador economy and provide income for struggling residents. An expanding seal hunt provided the most effective form of relief for fishers by creating work during the spring and winter, and by supplying a much-needed source of supplementary income. Merchant firms sent increasing numbers of schooners to the hunt each year and the colony's total harvest steadily increased from 126,315 pelts in 1815, to 227,193 in 1821, and 686,836 in 1831.

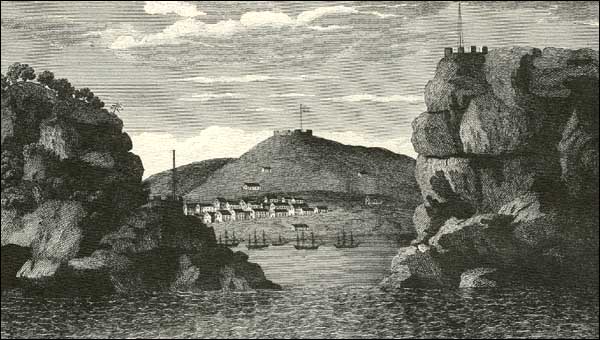

St. John's emerged as the island's administrative centre by the early 19th century and was able to support a wider range of workers than smaller communities, making it less dependent on the volatile fishery. This was in part due to the presence of government officials, magistrates, lawyers, and other members of the local elite who employed servants, physicians, teachers, and other workers to provide various services for themselves and their families. Gradually, the St. John's population expanded and became more complex – alongside numerous local fish workers, it also supported blacksmiths, coopers, carpenters, brewers, bakers, masons, tailors, shoemakers, shopkeepers, and other workers.

Agriculture also grew in importance, although on a much smaller scale than the seal hunt. Governor Sir Thomas Cochrane tried to encourage commercial farming by offering land grants, but the island's harsh climate, acidic soils, and rocky terrain limited its agricultural potential. Some Avalon Peninsula farms survived by selling vegetables, meat, poultry, and eggs to the relatively populous St. John's market, but agriculture never became an industry of any great importance in Newfoundland and Labrador. However, small-scale household farming became more important as many rural families maintained private vegetable gardens or kept chickens, cows, and other livestock.

Local cod fisheries also expanded into Labrador's inshore waters following the wars, which gave island fishers access to new cod stocks and reduced competition for popular fishing grounds. The colony developed new markets for its saltfish in Brazil, while its traditional trade links with southern Europe and the British West Indies eventually stabilized in the postwar years. Although the colony never experienced the same level of prosperity it enjoyed during hostilities, foreign demand for its codfish was fairly consistent for much of the 19th century and the fishery remained the mainstay of the Newfoundland and Labrador economy.