Great Depression - Impacts on the Working Class

The Great Depression was a time of widespread poverty and suffering in Newfoundland and Labrador. Steadily declining cod prices made it almost impossible for fishers to make a living, while wage cuts and layoffs plagued the forestry and mining industries. With thousands of men and women newly unemployed, the government was forced to spend heavily on relief programs. These, however, were often inadequate and left many people without enough food, clothing, and other necessities to properly support their families. Malnutrition became rampant and facilitated the spread of beriberi, tuberculosis and other diseases.

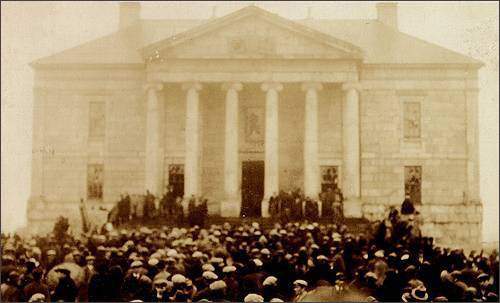

Unemployed workers became increasingly discontent and held street demonstrations to ask the government for jobs or better relief payments. Their dissatisfaction escalated into rage when allegations of fraud surfaced against Prime Minister Sir Richard Squires in the spring of 1932. Violent riots and protests occurred outside the Colonial Building and ultimately led to the ousting of Squires and the swearing in of the Commission of Government in 1934. The change, however, was of little help to unemployed workers, who still had to exist on inadequate relief payments.

Widespread Unemployment

Many people in Newfoundland and Labrador worked in the fishery or the forest and mining industries when the Great Depression broke out in 1929. As world trade declined during the 1930s, all three sectors suffered heavy losses. The country's iron ore exports fell from 1.6 million tons in 1930 to 194,000 tons in 1933. Newsprint exports to the United Stated also dropped from $9.1 million in 1930 to $4.1 million in 1935. There was an increased demand for newsprint from Britain, but pulp and paper companies still had to decrease wages and lay off employees to maintain profits.

As mining companies and paper mills dismissed workers and reduced salaries, fishers watched their profits disappear. Between 1929 and 1936, Newfoundland and Labrador's fish exports sank from $16 million to $7.3 million. Even in the best of times the country's fishers found it difficult to make ends meet, but the situation became desperate as prices for dried cod tumbled throughout the 1930s. Many fishers were continuously indebted to merchants who loaned them gear, food, and other supplies on credit and took their catch as payment. Some went into such deep debt that merchants refused to give them any more supplies on credit.

The Depression also forced other companies and industries to introduce cutbacks, making it almost impossible for unemployed workers to obtain jobs elsewhere. The government laid off close to one third of its civil servants during the Depression and imposed wage reductions on the rest. The postal service suffered heavy losses as approximately 300 offices closed across the country. Seasonal employment in Canada or the United States also disappeared as the Depression took its toll in those countries as well. Many Newfoundlanders and Labradorians already working abroad had to return home after losing their jobs; this exacerbated the country's already sizeable unemployment problem.

The Dole

With more companies laying off employees than hiring new ones, thousands of unemployed men and women turned to government relief for help during the Great Depression. Known as the dole, these payments were small and only provided about half of a person's total nutritional requirements. Applicants did not receive money to buy what they wanted, and instead had to accept items from a list. For example, a single adult on the dole could receive in one month: 25 pounds of flour, almost four pounds of fat back pork, two pounds of beans, two pounds of corn meal, one pound of split peas, three-quarters of a pound of cocoa, and one quart of molasses. St. John's residents also received vegetables, but people in the outports – where farmland was more plentiful – had to grow their own.

Many people resented the dole. They believed it did not provide them with enough food to live on and felt they should have the right to select their own groceries. The government, meanwhile, had little money to spend on relief because of a large national debt and shrinking income. It also worried that if payments were too large, the dole would become attractive and deter people from finding work elsewhere. Nonetheless, between one quarter and one third of the country's 300,000 residents were on the dole for each year of the 1930s; by 1933, the government was spending more than $1 million on relief annually.

Malnutrition became a problem and led to several deaths; poor diets and widespread poverty also contributed to a rising infant mortality rate and to the spread of tuberculosis, beriberi (which was lessened when the government added brown flour to dole rations), and other diseases. Unfortunately, medical attention was not free in Newfoundland and Labrador and many people could not afford the services of a doctor. School and rent were additional expenses which many people could not afford. Children stayed home if their parents could not buy them shoes and clothes, or pay school fees; landlords threw tenants out of homes if they could not afford rent.

If people did manage to save a small amount of cash for medical or other emergencies, they risked disqualification from the dole. Some government officials and members of the country's elite believed people were receiving relief when they did not really need it. As a result, the government gave relieving officers extensive powers to investigate dole applicants. This included the ability to search bank accounts. If a relief officer learned an applicant had money, grew vegetables, or poached rabbits or other animals, he or she could reduce dole payments or cut them off entirely. As historian James Overton notes, they could also force people to sell their possessions and live off any money earned before reapplying for relief.

Growing Discontent

As the Depression deepened, public dissatisfaction grew. People were cold, hungry, and poor; some even starved to death. Letters appeared in local newspapers complaining that dole rations were too small or asking the government for jobs. Others said the government was incompetent and should resign. Out of desperation, some people raided stores and stole food, clothes, or other goods. Protestors staged public demonstrations to ask the government for help, but these often resulted in only minor concessions. In 1935 for example, 1,000 people gathered in St. John's to demand that the government increase the dole by 50 per cent and include coal and clothing in rations. The only change, however, was an addition of turnips and cabbage.

Sometimes peaceful demonstrations turned into riots. This was the case in 1932 when finance minister Peter Cashin accused Prime Minister Sir Richard Squires of misusing public funds. On April 5, a public demonstration outside the Colonial Building escalated into a riot numbering 10,000 people. The mob threw stones at windows, raided the building, and looted government offices. Squires escaped unharmed with a police escort, but was removed from office in an ensuing election. The incoming government, led by Frederick Alderdice, ushered in the Commission of Government in 1934 and ended self-government in Newfoundland and Labrador.

The situation for the country's working class, however, did not improve under the new regime. Dole rations were slightly increased, but still did not provide enough food to remain healthy on. Particularly displeasing was the introduction of brown flour which was of a higher nutritional value than the previous white flour, but was difficult to bake with. For many, it was a reminder that they had little control over the foods they ate while on the dole. The appointed Commission of Government also left them with no control over who governed Newfoundland and Labrador.

Wartime Prosperity

It was not a change in administration or a new government policy that ended the economic hardships of the 1930s in Newfoundland and Labrador; it was the outbreak of World War Two in 1939. The establishment of foreign bases across the country suddenly created thousands of jobs for local workers. Enlistment was another avenue of ready employment. As jobs became available, the number of people receiving government relief plummeted from 75,144 in 1939 to 6,907 by the end of 1942. For many people, the war meant they could finally abandon the hated dole and once again support themselves and their family.