Civil Governors

Civil governors represented the authority of the crown in Newfoundland and Labrador and upheld the colony's Constitution. Between 1825 and 1855, the British government appointed five governors to office: Sir Thomas Cochrane (1825-1834), Sir Henry Prescott (1834-1841), Sir John Harvey (1841-1846), Sir John LeMarchant (1847-1852), and Ker Hamilton (1852-1855). Civil governors remained in power until the colony attained responsible government in 1855 and its first colonial governor, Sir Charles Darling, took office.

Civil governors had tremendous influence over the colony's governance, but their powers were neither absolute nor unchallenged. The rise of an independent press and political reform movement during the early-19th century made the colony's governing officials more accountable to the public than ever before, while the establishment of representative government in 1832 made it necessary for governors to work alongside an elected assembly for the first time.

Origins of Civil Governorship

Before the installation of a civilian governorship in 1825, officers with the British Royal Navy served as governors of Newfoundland and Labrador. Naval governors were appointed by the British government and ultimately under control of the British Admiralty. The system began operating in 1729, when Newfoundland and Labrador's seasonal population of migratory fishers far exceeded its permanent one.

This, however, was no longer the case by the early-19th century, when a resident fishery replaced the migratory one and Newfoundland became more populous than ever before. Some citizens began to agitate for political reform, arguing the system of naval rule was antiquated, ineffective or arbitrary. They believed a military government should not administer a civilian population and advocated for an elected legislature that would be answerable to the people instead of to the British government. Reformers also called for an overhaul of the judicial system, in which naval governors allowed men with no formal legal training to serve as surrogate judges in outport communities.

By the 1820s, widespread public discontent with the current system of administration placed pressure on the British government to respond. It passed a Judicature Act in 1824 granting Newfoundland and Labrador official colonial status and revamping its judicial system. London did not grant the colony representative government, but it did end the rule of naval governors and establish a civilian governorship.

Governor Sir Thomas Cochrane

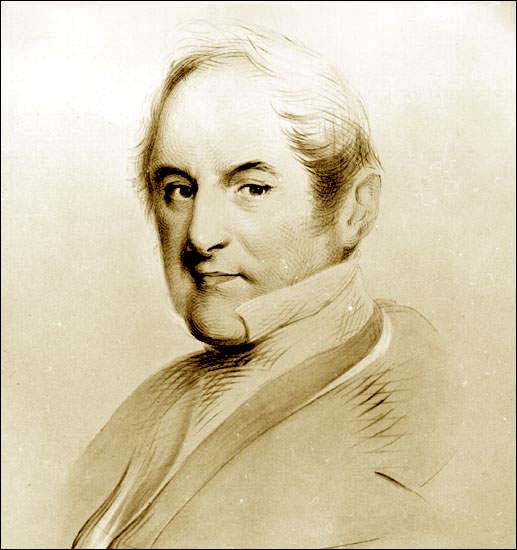

Britain appointed Sir Thomas Cochrane to serve as Newfoundland and Labrador's first civil governor. He arrived at St. John's in 1825 and remained in office for the next nine years. Although a civil governor, Cochrane was a naval officer and his powers under the Judicature Act were not initially very different from those of his naval predecessors. He ran the colony's political and legal affairs and, until 1832, did not share his powers with any elected officials.

While the Act allowed Cochrane to appoint a council consisting of the chief justice, two assistant judges, and a military commander, this was merely an advisory body that could not exercise any real power over the governor's actions. Cochrane also tried to establish a charter of incorporation for St. John's, which would have given the town a municipal government with the ability to pass bye-laws, but his efforts failed after local merchants opposed incorporation out of fear it would result in direct taxation, which many people in the colony wished to avoid.

As a result, Cochrane governed the colony without any input or opposition from elected officials for much of his time in office. However, the emergence of a local independent press and reform movement during the early-19th century provided the governor's office with more public scrutiny and criticism than ever before. Alongside the government-controlled Royal Gazette, a variety of independent newspapers existed on the island by the end of the 1820s; these included the Newfoundland Mercantile Journal, the Newfoundland Sentinel, the Public Ledger, the Newfoundlander, the Harbor Grace and Carbonear Weekly Journal, and the Conception Bay Mercury.

In addition, some residents began circulating protest pamphlets to the general public; prominent writers included reformers William Carson and Patrick Morris. For the first time in the colony's history, its citizens had easy access to mass-produced written material publicizing and evaluating government actions and policy. Although not all publications were opposed to Cochrane's governorship, they did provide the public with an unprecedented ability to collectively discuss and scrutinize the colony's leadership.

Representative Government and the Governorship

Growing pressure from the reform movement prompted Britain to grant Newfoundland and Labrador representative government in 1832, forcing Cochrane to share power with political representatives elected by eligible voters. Alongside the governor and an appointed Board of Council, an elected House of Assembly also governed the colony; any new laws the government passed had to receive approval from both the Council and the Assembly.

The governor, however, remained a politically powerful figure following the change in government structure. He opened and dissolved all legislative sessions and retained the ability to prorogue the House of Assembly. The governor could submit bills to the House for debate and had to support any new legislation before it was made into law. Although the British Government ultimately approved or rejected all new bills affecting Newfoundland and Labrador, it received suggestions from the governor, who reported directly to the British Colonial Office.

Tensions existed between the appointed board and elected assembly. Elected officials sought to increase their political powers, while many board members were opposed to representative government; as a result, conflict often accompanied government business. In 1842 the colony's new governor, Sir John Harvey, and the Colonial Office tried to bring greater harmony to the Newfoundland and Labrador system of government by merging the council and assembly under a single temporary Amalgamated Assembly that would operate for six years.

The system worked relatively smoothly under Harvey's governorship, but former tensions reemerged once the amalgamated assembly dissolved in 1848 and was replaced by the previous bicameral system. The government structure remained unchanged until 1855, when a new system of Responsible Government came into effect.

Governors

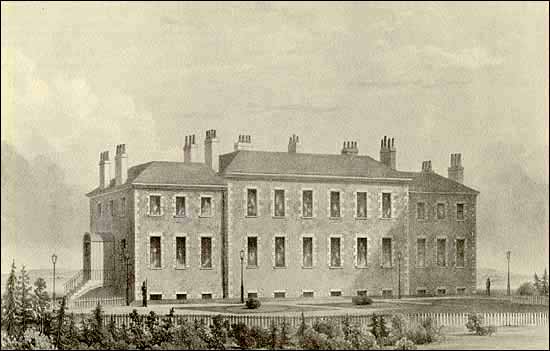

Britain appointed five civil governors to office between 1825 and 1855. Some made considerable impacts on Newfoundland and Labrador society, while others made minimal contributions. Sir Thomas Cochrane, for example, encouraged agricultural development and road building, and also commissioned the building of an extravagant Government House on Military Road in St. John's, which was completed in 1831.

Sir Henry Prescott introduced the colony's first education legislation during his term, while Sir John Harvey promoted agriculture, road building, and communications. Harvey supported the development of a local police force, established a regular steamer service between St. John's and Halifax, and helped to form the Newfoundland Agricultural Society.

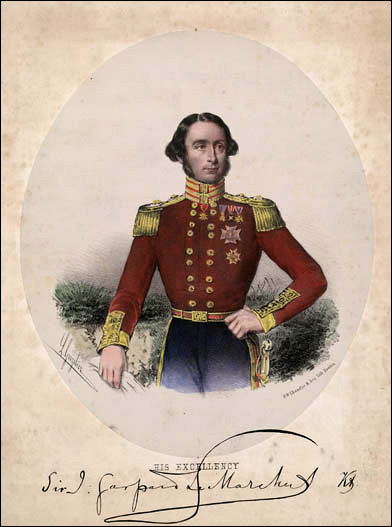

Sir John LeMarchant was an unpopular governor during his term between 1847 and 1852. He took office following a fire that left thousands homeless in St. John's, yet redirected relief money to pay for various public works, which included repairs to his residence at Government House. LeMarchant also exacerbated sectarian tensions in the colony by supporting Anglican Bishop Edward Feild, who opposed public funding for Roman Catholic schools and Methodist rights surrounding education, marriage, and baptism.

Ker Hamilton was governor for a relatively brief period, serving from 1852 until 1855. During that time, the colony was absorbed in debates surrounding the establishment of responsible government. Hamilton opposed Britain's decision to grant Newfoundland and Labrador responsible government in 1854 and tried to subvert its implementation, in part by delaying elections until 1855. That same year, Britain appointed Sir Charles Darling to serve as the colony's first colonial governor.