Centralization

But me I just calls it the Government Game.”

Pat & Joe Byrne

“The Government Game”

Towards the Sunset

1983

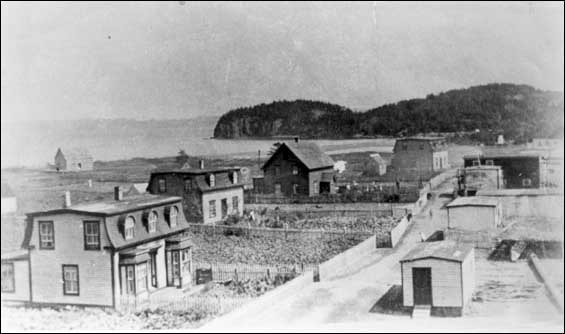

The central focus of the Smallwood government's programme was to diversify, industrialize and modernize the provincial economy. An essential part of this strategy was the provision of basic services such as health care, education, electricity and transportation to all residents of the province. But with some 1,200 outport communities dotted along the 28,956 kilometre coastline of the island and Labrador, the price tag would be enormous. Few outport communities had populations of over 500. There were 573 communities with thirty or fewer families, 126 with five to ten families, 185 with eleven to twenty families and 131 with twenty-one to thirty families. The answer seemed to lie in encouraging people living in small, remote communities to move to places that were larger and more accessible.

Introduction of the Centralization Programme

It is sometimes alleged that the first resettlement programme was prompted by requests for government help to relocate coming from people living on islands along the northeast coast of Bonavista Bay. Whatever the truth of this, in 1954 the Smallwood government introduced a 'Centralization Programme' which offered monetary assistance to people who wanted to move to larger centres of their own choosing. The programme was operated by the Department of Welfare, and offered a relocation subsidy that averaged $301 per family, up to a maximum of $600, though payments of this size were rare. By 1959, 29 communities containing around 2,400 people had been resettled with government assistance. The cost was $146,027.

The Centralization Programme was assessed in the late 1950s, with a view to its expansion. As a first step, in November 1957 the provincial government's economist sent a questionnaire to clergy, doctors, and other professionals throughout the province, seeking their opinion about which communities in their districts should be resettled. The replies identified 199 communities with a total population of 14,800 people. The provincial economist's final report (1960) also showed that in addition to government- supported centralization, there was a significant amount of 'private' resettlement going on - that is, some families and communities were moving voluntarily and without subsidization. Though figures were not available, the report suggested that the number of 'private' resettlers exceeded the number that received government aid. (Report on Resettlement in Newfoundland, 11). On the other hand, it was also clear that some of the communities that had been identified as potential candidates for resettlement were neither ready nor willing to move.

It was also evident that the financial subsidy would have to be improved. Short-distance moves were very common, since people tended to choose their new communities on the basis of family ties and religious affiliation, and often floated their houses to the new destination. Nevertheless, there were costs involved. Some families had to buy or build new houses, and money had to be found to pay municipal taxes and purchase services. In theory, families relocated to communities that had better services and were not isolated, but this did not necessarily mean that families were economically better off. Newly relocated fishers had difficulty catching the same amount of fish as formerly, because they did not know the new fishing grounds. In some cases families returned to their old communities during the fishing season. Providing upkeep for two separate households was neither easy nor practical, but fishers thought that half a living was better than nothing.

Social Impact of Centralization

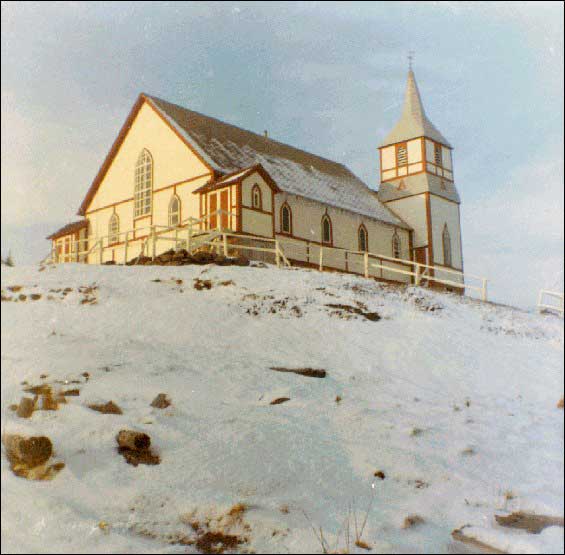

By the 1960s there was a growing recognition that the social impact of centralization was significant. Families used to an isolated, rural lifestyle needed help in adjusting to life in a town. The very existence of the Centralization Programme was the cause of stress. Many people feared that the government would force them to leave their communities. Stories circulated that the churches would refuse to send clergy to the outports, or that teachers would not come to isolated areas. Rumors spread unchecked, causing passionate and emotional debates that could divide friends and families against each other. This occurred because resettlement was community-focused: every member of a community had to sign a document indicating they were willing to move. No money was paid until the last household left.

Pat Canning, the MHA for Placentia Bay during the resettlement years, indicated that "resettlement was people-inspired ...it was already happening when the Government came into business in 1949." (Decks Awash, 52) This is true, but a significant number of those who resettled in the 1954-65 period spoke of the pressure placed on them to move - for instance, if the main merchant decided to leave, then it was hard for the residents to stay. In all, 115 communities with about 8,000 people were resettled under 'centralization', between 1954 and 1965.

From the government's point of view, the programme had proved worthwhile in gathering people into larger, more easily-accessed centres. It was certainly a practical solution to the problem of providing modern services. But there was not enough employment, and the programme was an expensive venture for the province. By 1965 the provincial government had persuaded the federal government to help. Thus the second phase of resettlement was to be a partnership between the federal and provincial governments, which focused its efforts on relocating people to designated 'growth centres'.