Impact of Non-Indigenous Activities on the Inuit

Since European fishing crews began making annual trips to Newfoundland and Labrador in the 1500s, non-Indigenous activities have altered Inuit culture and society. Early European visitors and settlers introduced metal tools and other manufactured goods to the Inuit, Moravian missionaries converted many Inuit to Christianity, and North America's predominately English-speaking society forced the Inuktitut language into decline during the 20th century.

To safeguard their cultural traditions against increasingly intrusive outside forces, Labrador's Inuit people formed the Labrador Inuit Association in 1973 and later filed a land claim with the federal and provincial governments that ended successfully in 2004. As a result of the agreement, Labrador's Inuit are now a self-governing people who have rights to 72,520 square kilometers of land in northern Labrador known as Nunatsiavut. Although the Inuit people's struggle to preserve their culture and interests against external threats has not yet ended, the formation of Nunatsiavut has given the Inuit increased control over their lands, governance, and cultural traditions.

Contact with European Settlers

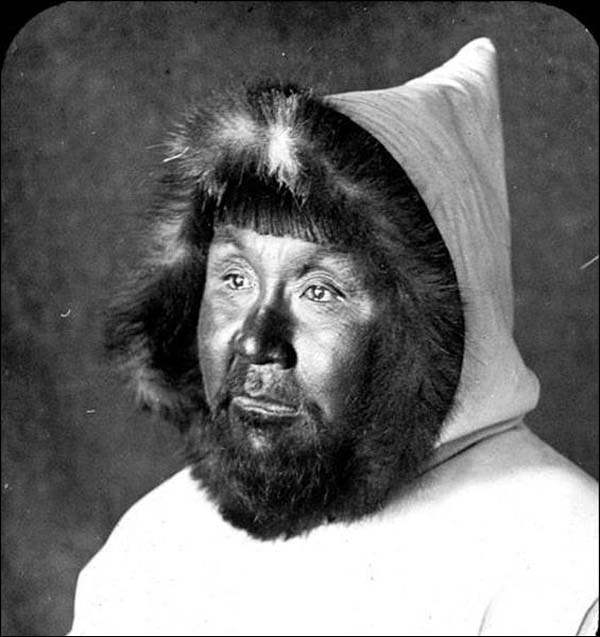

Beginning in the early 16th century, European fishing and whaling crews traveled to the Labrador coast each year from across the Atlantic. Although they often came into contact with Labrador's Indigenous peoples, their presence did not greatly alter Inuit society and culture. Inuit families continued to make seasonal use of local resources, adhering to their traditionally nomadic lifestyle and economy. Some Inuit began traveling south each summer to trade with the Europeans, where they acquired metal tools, wooden boats, and other forms of technology for the first time.

As contact between the two cultures became more common, frictions emerged which often ended in violence. To curb mounting hostilities, Newfoundland and Labrador Governor Sir Hugh Palliser asked the Moravians – a protestant sect that worked with Greenland's Inuit people – to establish mission stations in Labrador. The Moravians agreed and in 1771 opened their first station at Nain; others later followed at Okak (1776), Hopedale (1782), Hebron (1830), and Makkovik (1896). By the mid-1800s, up to 300 Inuit spent their winters at each mission station before traveling to hunting and fishing grounds in the spring and summer.

Soon after the stations opened, hostilities ended between Inuit traders and European fishers. The Moravians forbade Europeans from entering mission grounds and took over all trade operations with the Inuit. Alongside restoring peace, however, the Moravians initiated a new era of sustained and close contact between the Inuit and European peoples that would dramatically alter the Inuit way of life. In addition to conducting trade operations, the Moravians provided the Inuit with religious, educational, and medical services. Although the Moravians were careful to preserve certain parts of the Inuit culture – they isolated Inuit from European traders, taught reading and writing in Inuktitut, and provided Inuktitut translations of the New Testament – they also promoted Christian practices and ideals that eroded the Inuit belief system. In addition, the mission indirectly encouraged families to restrict their nomadic practices and settle at least semi-permanently near one of the Moravian stations.

By the mid-19th century, many European settlers also moved into communities near the Moravian stations. As contact with Inuit people became more common, marriages occurred between European men and Inuit women. It was not unusual for the men to convert to the Moravian faith and adopt various Inuit practices. The offspring of such unions resulted in a new group of people known in Inuktitut as Kablunângajuit (which means 'partly white men') and in English as Settlers. Many Southern Inuit of NunatuKavut trace their roots to these Inuit and European marriages. Increased contact with non-Indigenous also introduced Inuit to alcohol, unfamiliar foods, and new forms of manufactured goods. They also contracted dangerous new diseases, the most devastating of which was the 1918 Spanish influenza.

Fur Traders

Financial difficulties forced the Moravian Mission to lease its Labrador lands and trading rights to the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) in 1926, placing many Inuit people in direct contact with the commercial business for the first time. In contrast to the Moravians, who conducted a relatively fair and generalized trade with the Inuit to support their diversified economy, the HBC concentrated much of its efforts on the fur trade. This encouraged the Inuit to abandon or decrease many of their other activities, including sealing and fishing, to trade fur year-round with the HBC in return for credit at company stores.

Rising dependence on the fur trade and on HBC stores for manufactured goods and imported foods undermined the Inuit people's subsistence economy and made them more vulnerable to outside forces over which they had no control. When the price of furs dropped during the Great Depression, many Inuit families fell into deep poverty. This was compounded by increased health problems among the Inuit people, arising from sudden changes in diet and lifestyle.

To alleviate some of the financial problems plaguing local residents, the Newfoundland and Labrador government stationed a new police force, the Newfoundland Ranger Force, at Labrador in 1935. Alongside enforcing the law, rangers distributed government relief payments to local residents and often served as the only link between Labrador people and the seat of government at St. John's.

Prior to the 1930s, government involvement with Inuit and other Indigenous peoples in Labrador was almost nonexistent. Indigenous lands were usually remote from the centre of government and trade or other operations between European settlers and Indigenous peoples did not evolve to the extent that they required specific legislation. Contact between Indigenous people and government officials was rare and it was often religious groups, like the Moravians, or traders, like the HBC, that administered Labrador's daily affairs.

The Newfoundland and Labrador government became more actively involved in Inuit affairs after the HBC closed its Labrador operations in 1942, due in part to declining profits. The government assumed responsibility for all trading stations at northern Labrador and promoted a return to the diversified Inuit economy by accepting goods other than furs.

By then, however, the Second World War had dramatically altered the way of life for many Labrador residents. The construction of a large military airport at Goose Bay and of smaller radar bases along the coast provided some Inuit workers with jobs and allowed them to earn cash wages for the first time. Close exposure to American and Canadian troops and the introduction of new roads and better modes of communications exposed local residents to higher standards of living, as well as to new ideas and lifestyles. In the coming years and decades, North American society would encroach even deeper into Inuit territory and consciousness.

Confederation

At the time of Confederation, at least 700 Inuit lived in Labrador. Aside from their widespread conversion to Christianity, almost every other aspect of Inuit culture was intact – most spoke Inuktitut, lived in their traditional lands, and maintained a seasonal subsistence economy that largely consisted of hunting and fishing.

After Newfoundland and Labrador joined Canada in 1949, provincial and federal government agencies began to deliver health, education, and other services in Inuit communities. Unlike the Moravians, who tried to preserve Inuit language and culture, early government programs rarely took these issues into concern. Teachers, for example, delivered lessons in English, while most health and other workers could not speak Inuktitut. This contributed to the marginalization of the Inuit language – between 1971 and 1981, the number of Labrador Inuit using Inuktitut as their home language dropped from 75 to 57.5 per cent.

Students also became alienated from a school curriculum that did not reflect their society or use their mother tongue. Many dropped out before graduation, making it difficult for them find jobs in an increasingly competitive labour force. At the same time, many young Inuit could not take up the traditional lifestyles of their parents and grandparents because they had spent their childhoods in the classroom rather than on the country. As a result, many young Inuit became estranged from both their traditional culture and the modern labour force.

The high costs of delivering services to remote Labrador communities prompted the provincial government, Grenfell Association, and Moravian officials to close the Inuit communities of Nutak and Hebron in the 1950s and relocate residents to Nain, Hopedale, and Makkovik. Like resettlement programs taking place in rural Newfoundland communities at the same time, the closure of Hebron and Nutak created many far-reaching social and economic problems for those involved. At Nain, for example, the influx of new residents led to increased competition for local resources and created tensions between new arrivals and long-time residents.

In the coming decades, industrial development, advances in technology, and more efficient modes of communication further threatened Inuit culture and society. North American television and radio shows – almost all targeted toward a white English-speaking audience – and a wide range of consumer products became more widespread after Confederation and helped change local values and attitudes. New game and fishing laws also limited the Inuit people's traditional use of their land and resources. As mainstream society continued to marginalize Indigenous peoples, poverty, alcoholism, and other forms of substance abuse became reoccurring problems in many communities.

Labrador Inuit Association

To better-protect their culture and rights, Labrador's Inuit people formed the Labrador Inuit Association (LIA) in 1973. Four years later, the LIA filed a land claim with the provincial and federal governments for 72,520 square kilometers of land and 44,030 square kilometers of sea in northern Labrador. Negotiations began in 1988 and were successfully completed on 6 December 2004 when the provincial government passed the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement Act.

As a result of the Act, the Labrador Inuit are now a self-governing people under the Nunatsiavut Government. Their land, Nunatsiavut (“Our Beautiful Land” in Inuktitut), stretches along the northern Labrador coast and includes the communities of Nain, Hopedale, Rigolet, Makkovik, and Postville. Within their settlement area, Inuit have the right to harvest fish and marine mammals for food and ceremonial purposes. They also receive five per cent of provincial revenues from the Voisey's Bay nickel mine, located about 35 kilometres southwest of Nain. In 2005, the Newfoundland and Labrador government made a formal apology to Inuit families it forcibly removed from Nutak and Hebron in the 1950s; it also paid $63,000 in compensation to those involved.

Today, the Nunatsiavut Government represents about 5,000 Inuit. Although pressures continue to threaten their culture, the success of the land claim agreement and subsequent formation of the Nunatsiavut Government are significant steps toward the preservation of Inuit language, culture, and society.