Beothuk Housing

The Beothuk's frequent moves from one resource to another and the seasonal nature of their occupation of camps resulted in a variety of styles and construction methods of mamateeks (the Beothuk word for houses). Some dwellings were intended to shelter a family during the summer season; others would have been designed for a larger group for the winter or for repeated use over several years.

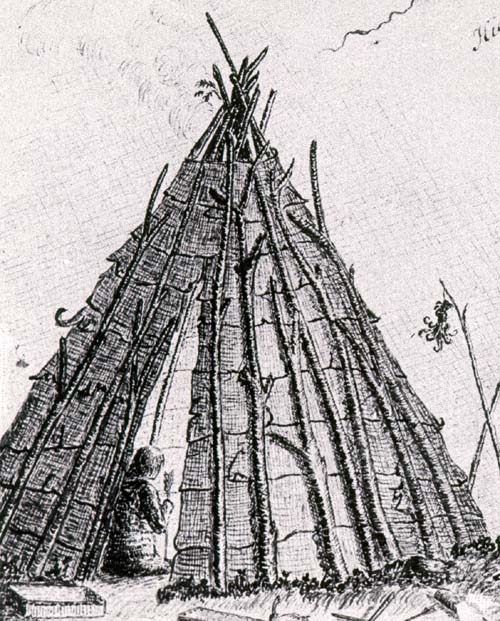

The Conical Summer Mamateek

The most easily constructed house type was the conical summer mamateek. First, the forest floor was cleared of grass cover and loose soil, which were scraped into a low earthen wall around the perimeter. Several poles, set in a circle and fastened together at the top, made up the frame. Large birchbark sheets, sewn together, were placed around the circumference of the frame from the bottom upwards, overlapping like shingles. An opening was left at the top of the structure so that smoke could escape. More poles were leaned against it from the outside to keep the cover in place. After contact with fishing crews and settlers, the Beothuk also used old sails as cover material.

Inside there was a central fireplace surrounded by sleeping hollows. These hollows, which appear to have been unique to the Beothuk, were dug into the ground and lined with branches of fir or pine. Because they were relatively short some observers believed that the Beothuk slept in a sitting position or curled up. Summer mamateeks normally housed between three and eight people, although larger dwellings of this type may also have been built.

Larger Dwellings

The Beothuk also built square or rectangular dwellings. The one described by John Cartwright, in 1768, had been framed in the manner of English houses. Three of its walls were insulated with caribou skins, the fourth wall was made of tree trunks placed horizontally, one upon the other; the cracks were filled with moss. The roof was of a low pyramid shape with a hole in the centre to allow smoke to pass.

Larger dwellings of different designs were multi-sided. A dwelling with a five-sided floor plan approximately 6 x 7 m has been excavated on the banks of the Exploits River. A six-sided mamateek, measuring about 6 x 7.5 m, presumed to have been a winter dwelling, was excavated at Indian Point, Red Indian Lake. It was dated at circa AD 1595. The roof, most likely of a conical shape, would have rested on the forest floor. Inside, the floor had been dug out, in places to a depth of 1.5 m. There was a large central hearth with sleeping hollows around it.

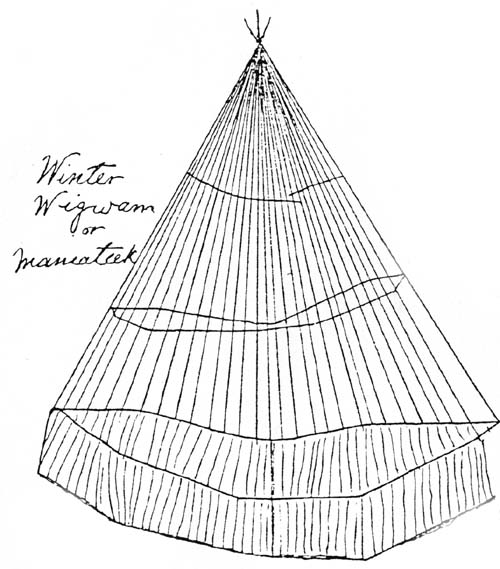

Winter Mamateeks

By the early 1800s, the construction methods of winter dwellings had changed. Captain Buchan described an eight-sided mamateek made of tree trunks that had been pounded upright into the ground, one next to the other. The conical roof, made of poles, was covered with birchbark. (Another report mentions a roof that had three layers of birchbark, with a 15 cm layer of moss wedged between the first and second layer.) On the outside, the walls were banked with soil; inside, they were covered with skins. Some houses had beams on which food was stored. The occupants slept around the central hearth with their feet towards the fire and their heads towards the walls. Captain Buchan found the house comfortably warm.

To date, there is no archaeological record of the house type constructed from tree trunks in the manner described above. It is most likely that these compact dwellings only existed in more permanent Beothuk settlements, such as those recorded from Red Indian and North Twin lakes, which have since been flooded.

Whether Shanawdithit's drawing of a winter mamateek is meant to depict a six- or eight-sided dwelling cannot be determined.

Oval Mamateeks

In addition to multi-sided dwellings, archaeologists have also identified the remains of oval-shaped mamateeks. One of two oval house pits at the Boyd's Cove site measured about 6 x 9 m. The hearth inside this structure was elongated and had an extensive accumulation of caribou bone mash, believed to be the remains of communal feasts known among the Innu of Labrador as mokoshan. Their name for the house used for this purpose is shaputuan. The feasts were celebrated in honour of the caribou spirit and involved the extraction, boiling and consumption of substantial amounts of marrow from caribou leg-bones. As has been mentioned in an earlier section, this was an important feature in the Beothuk's spiritual life.

Changing Building Techniques

Records indicate that the style and techniques used in building Beothuk houses changed over time. During the first two or three centuries after contact with Europeans the Beothuk lived in conical mamateeks all year round. Most likely, those built for summer use were lighter structures than winter mamateeks, which would have been more durable and better insulated. Not until the 1800s is there a record of more solidly built winter quarters with walls made from upright tree trunks. This development was likely influenced by the building methods used by fishermen and by the availability of their tools and gear; for example, iron axes, which made the cutting of trees less laborious, would have encouraged the Beothuk to use more mature trees. Canvas sails, which were waterproof and could easily be stored, became a favoured material for covering mamateeks.

The Beothuk also built smoke- and store-houses as well as sweat baths. The latter consisted of a dome-shaped framework, covered closely with skins, placed over a pile of heated stones. The user would creep underneath the cover with a bucket of water and produce steam by pouring small quantities over the hot stones. According to Shanawdithit, steam baths were mostly taken by older people or by those who sought relief from illness.