Sponsored Settlement: The Colonization of Newfoundland

In late 16th century England, there was a growing interest in planting colonies in North America, including Newfoundland. Among those promoting such schemes were Anthony Parkhurst, who published a pamphlet about Newfoundland in 1578, and Sir Humphrey Gilbert, who called at St. John's harbour in 1583 on his ill-fated voyage to the mainland.

A member of that expedition, Edward Hayes, also promoted the idea of Newfoundland colonization. Such schemes were often linked to the false belief that climatic conditions in North America generally, and in Newfoundland in particular, would be the same as countries like England and France that were at the same latitude.

Such schemes were also motivated in considerable measure by a desire to extend English control over a fishery and fish trade which, in the late 1500s, was dominated by other countries. These early proposals therefore placed much emphasis on fortifications, territorial claims, and armed garrisons.

Establishing Colonies

However, nothing of consequence happened until the end of England's war with Spain in 1604. With peace came a tremendous increase in overseas investment and activities. New trading companies, such as the British East India Company (1600), were formed and colonies began to be regarded as a form of investment that would produce handsome profits through the development of local resources. Thus, the first English overseas plantation was established in Virginia in 1607. The second such venture, established shortly thereafter, in 1610, was John Guy's settlement at Cupids, Conception Bay, Newfoundland. Soon, there were many attempts to establish colonies in the New World, from Newfoundland to coastal North America and down to the Caribbean.

Initially, they were two basic types of colony in Newfoundland and other parts of North America. Those such as Cupids, undertaken as business ventures by groups of investors, were called charter colonies. Others, such as Ferryland and Renews, launched by an individual proprietors, were called proprietary colonies.

The investors in the London and Bristol Company (known simply as "the Newfoundland Company") who sponsored the plantation at Cupids, either had some experience in the fishery and trade (these were the Bristol subscribers) or else had capital as well as commercial and political connections (these were the London merchants and the courtiers). Their plan was to establish not just one settlement at Cupid's Cove, but eventually a series of settlements through which the company would eventually control the Newfoundland fishery and, in consequence, the trade. The venture was placed in the charge of John Guy, a Bristol merchant with previous experience at Newfoundland and one of the founding investors.

The colony at Cupid's Cove hoped to profit from agricultural, forest and mineral resources. When profits failed to materialize, the Company began selling tracts of land to other promoters such as Sir William Vaughan, who established a short-lived colony at Renews. Vaughan in turn transferred sections of his grant to Lord Falkland, and to Sir George Calvert, later Lord Baltimore, who established the Colony of Avalon at Ferryland.

Sir William Vaughan was a visionary who saw overseas colonization as a solution to social and economic problems at home, such as overpopulation, unemployment, and poverty. George Calvert, later Lord Baltimore, who founded the colony of Ferryland in 1621, clearly believed that overseas colonies could be profitable ventures, but he also viewed his plantation as a haven of religious toleration. Despite official discrimination against Roman Catholics in Protestant England, Calvert, who was himself converted to the Catholic faith, allowed both Roman Catholic and Anglican clergy to serve at Ferryland.

Problems with Colonization

Though informal settlement persisted on a small scale from the early 16th century, all of the charter and proprietary colonies failed. Why was this? Simply put, the settlers and their backers found it difficult to sustain year-round habitation at Newfoundland — and impossible to make a profit. At Cupids and its offshoot Bristol's Hope, for instance, the settlers found agriculture difficult, the climate harsh, precious minerals non-existent, and the fishery a struggle because of competition from migratory ships and the aggression of pirates such as Peter Easton. Because emigrants leaving England were attracted to the mainland colonies rather than to Newfoundland, the population remained small and precarious, and investors eventually gave up. A colony-for-profit could only succeed if there were enough resources to sustain the colonists for year round and to support a profit-generating export trade. In Newfoundland, only the fishery held out such a prospect. However, it only functioned for four or five months of the year. The fishery could generate (and for over a century it had generated) substantial profits, but only so long as it was a seasonal and migratory activity based in England.

This did not mean that settlement itself had failed. What had failed was collective settlement sponsored from England. Archaeological research at Ferryland and more recently at Cupids Cove indicates that settlement by planters had by then become a small but permanent fixture on the island.

The French Colony of Plaisance

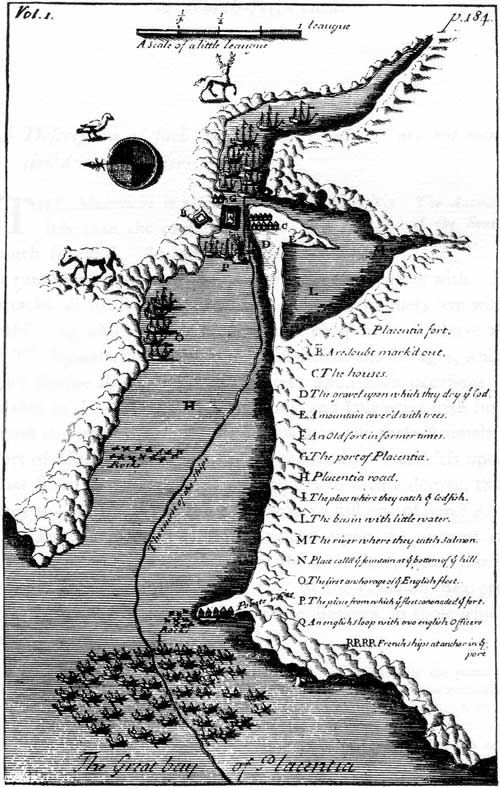

Besides the English plantations, there was one important attempt to establish a French colony in Newfoundland. The colony at Plaisance (Placentia) was not sponsored by private investors or individuals, like the English charter and proprietary colonies; it was a royal colony, founded by the French Crown to serve the interests of the state. Frenchmen engaged in the flourishing migratory fishery had for many years used the fine beach at Placentia to dry their fish, and proposals for a colony there were put forward as early as 1655, but it was not until 1664 that sustained funding was provided for such a venture. For Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the powerful Minister of Finance (and the Colonies), a permanent settlement at Placentia was part of a grand scheme to integrate and strengthen France's involvement in trans-Atlantic commerce.

A. Placentia fort.

B. A redoubt mark'd out.

C. The houses.

D. The gravel upon which they dry ye Cod.

E. A mountain cover'd with trees.

F. An old fort in former times.

G. The port of Placentia.

H. Placentia road.

I. The place where they catch ye Codfish.

L. The basin with little water.

M. The river where they catch Salmon.

N. The place calld ye fountain at ye bottom of ye hill.

O. The first anchorage of ye English fleet.

P. The place from ye fleet carronade ye fort.

Q. An English sloop with two English officers.

RRRR. French ships at anchor in ye port.

The colony, however, faced many of the same difficulties as the English colonies had encountered. Heavy investment in soldiers, fortifications, sponsored emigrants, and direct subsidies yielded little benefit, and efforts to diversify the economy proved fruitless Finally, at the end of the War of the Spanish Succession (1702-13), the French government abandoned Placentia in order to make a fresh start in Cape Breton, where they established the fortified colony of Louisbourg.