Social History 1760-1830

Considerable uncertainty surrounds our understanding of daily life in Newfoundland during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Numerous documents and published reports describe the colony's economy and government during this period, but few shed light on its social history. Low literacy rates, particularly in rural areas, prevented residents from leaving behind first-hand accounts of their daily routines.

Virtually all reports come from the writings of travelling men - missionaries, geologists, naturalists, explorers - whose work brought them to remote communities for brief visits, often for a night or two. These visitors came from different social classes than the settlers they wrote about in their journals and letters. Their accounts of community life are valuable, but are often brief, incomplete, incidental, and clouded by an outsider's lack of understanding for an unfamiliar culture. Thus, it is through the imperfect eye of the stranger that we acquire an understanding of daily life in Newfoundland at the turn of the 19th century.

Who Lived Here?

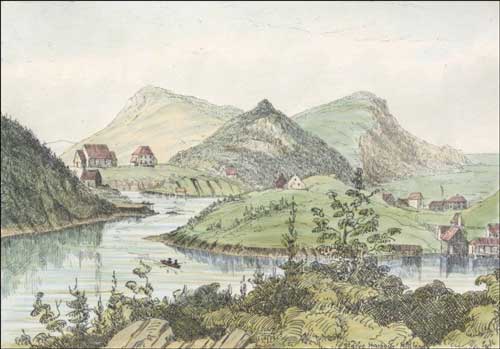

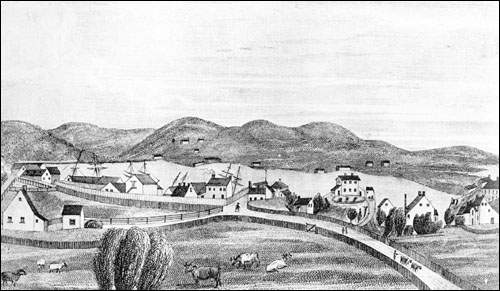

Newfoundland's population expanded and stabilized in the late 1700s and early 1800s. As the migratory fishery gave way to a resident industry, increasing numbers of Europeans - principally from southwest England and southeast Ireland - settled on the island and started families. Immigration and climbing birth rates boosted the population from 11,382 in 1797 to 40,568 in 1815. Large centres existed at Conception Bay and St. John's, but most people lived in remote coastal settlements. They were principally fishing families who engaged in a variety of supplemental activities, such as hunting, small-scale farming, and logging.

Daily life was difficult. Imports were not always available and government services virtually non-existent. Families had to provide much of their own food and shelter from the resources at hand. All household members were expected to help out, leaving little time for leisure. Activities varied with the seasons and from one region of the island to another.

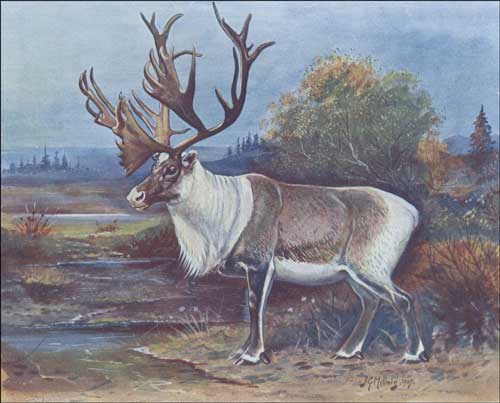

Many families had two homes - one near the ocean for the warmer months and another in the woods for the winter. Seasonal mobility allowed them to harvest different resources as they became available. In the spring and summer, coastal resources were plentiful: fish, marine mammals, and sea birds. Vegetables could be cultivated and berries harvested. In the winter, the woods provided shelter from harsh weather and easy access to wood for fire and the construction of boats, oars, and other equipment. Caribou and other game animals were available.

Spring and Summer

Between March and May, most people returned to their summer homes by the sea. Some outports consisted of only one or two families, others had dozens. Roads rarely connected one settlement to another and the ocean was the main mode of transportation. Houses were scattered irregularly around the bay and connected to one another by rough foot paths. They were generally one or two stories high and built of wood harvested locally. Some had clapboard (long thin timber boards overlapping one another) on the outside, and others were simple log huts. Most houses were unpainted. Floors were made of wood, either planks or 'longers': long poles, usually thin conifer branches or trunks, gathered from nearby forests. Shingles, if used, were imported. If a merchant lived in a community, his house was larger, usually painted white, and built on a stone or brick foundation.

Most outport families kept vegetable gardens near their homes. They grew crops that were easy to care for, preserved well, and were compatible with Newfoundland's poor soil and cold climate. Cabbages were popular, alongside a variety of root vegetables: potatoes, turnip, carrots, parsnip, beets, and onions. Poultry and livestock were often present and could include hens, ducks, geese, cows, sheep, goats, and pigs - although such a variety for a single family would have been rare. The Newfoundland dog was popular as both pet and work animal. It helped to haul wood in the winter and hunt fowl in the summer.

Families were large. Six or more children were not uncommon, and sometimes a few generations lived under a single roof. Work dominated the daily routine: harvesting resources from the land and sea, preparing meals, building or repairing nets and other equipment, knitting or weaving, caring for the young and elderly, and a multitude of other household chores. All family members helped out and work was divided by gender and age. Schools were largely absent from outports, so children stayed home and worked instead.

How a Day May Have Unfolded

A typical day would have begun early and, depending on how religious a family was, with morning prayers. Breakfast often consisted of tea with fish and brews, or perhaps hard bread and molasses. Afterwards, family members separated to perform their tasks. The father and any adult sons rowed out to fishing grounds in small open boats. On land, the women and children were kept busy with an assortment of tasks. Inside, they scrubbed floors and cleaned beds. Clothes were washed by hand. Outside, they tended vegetable gardens and cared for any hens and livestock. Further from home, they picked berries to later preserve in jams, jellies, and wine. If they were near a salmon brook, they managed the nets.

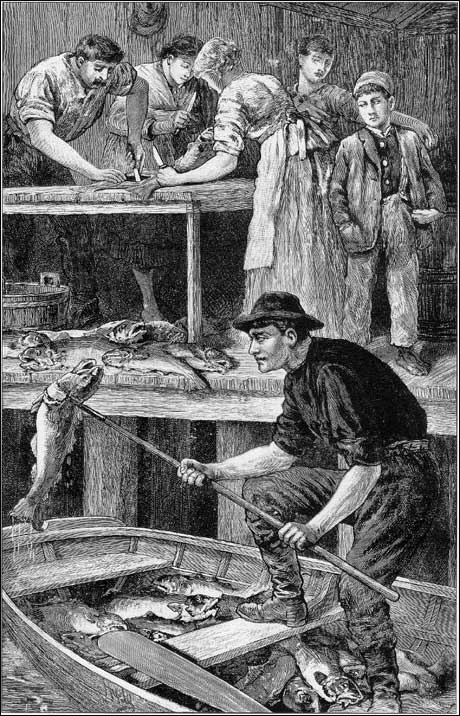

Once the men returned home with cod, the entire family helped to unload the catch. After a brief meal, which may have consisted of fish and potatoes, the men likely returned to the fishing grounds if it was not too late in the day. It was often up to the women and children to process the cod. They removed the head and backbone, covered the fish with salt, and spread it out on flakes to dry in the sun and air. On rainy days, they would have to cover the fish or bring it inside.

After a long day of work, the family returned home. Tea and fish would likely have been served at supper, supplemented by other foods, such as fresh or preserved vegetables, hard or soft bread with butter, eggs, and milk. On Sundays and special occasions, salt pork or beef was often served.

Although remarkably self-sufficient, families could not provide for all of their needs and relied on imports. At certain times of the year (often spring) coastal boats brought supplies of bread, butter, tea, sugar, nets, hooks, clothes, and other goods. Residents could also visit merchant stores, but this could mean a day's journey or longer if the merchant lived in another settlement. Many families traded fish for store credit.

Fall and Winter

Between October and December, many coastal residents moved to their winter homes. Some families journeyed 30 miles or more, taking with them their furniture, boats, and other belongings. Although common, 'winterhousing' was not a universal practice and some people lived in coastal communities year-round.

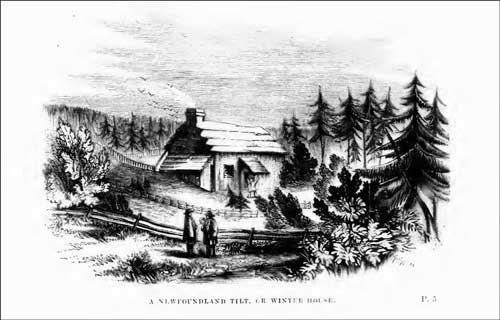

Winter homes, or 'tilts' were vertical log huts, usually built on a clearing in the woods. They were more primitive than summer dwellings and only intended to last for two or three years. An ideal location provided shelter from stormy weather, a nearby source of drinking water, such as a pond or river, and a good supply of wood. Early tilts were quite small and often consisted of a single room (one was reported to measure only twelve feet by ten), while later tilts could be larger, sometimes two-stories high with two or more rooms on each floor.

A single fireplace heated the cabin and was the focal point of family life. It was typically made of stone with a wooden chimney. Gaps between the boards were plugged with moss, but smoke often escaped into the living space itself, irritating eyes and earning the nickname 'cruel steam'. Families sometimes used the chimney to smoke salmon and other fish. Warmth from the fire also allowed some people to keep chickens - and a source of fresh eggs - inside their huts throughout the winter.

Daily life was still busy, but new activities replaced the summer routine. Logging and hauling wood was an ongoing task. Wood provided fuel for the fireplace and building materials for boats, oars, flakes, and other equipment that would be needed the following summer. Men hunted caribou and wild fowl, or trapped smaller mammals for furs and food. Women made or mended clothes, kept the household tidy, raised and educated children, and prepared meals.

By the spring, families abandoned their winter homes and journeyed back to their coastal communities to begin another seasonal round. Such mobility was in part made possible by an almost complete lack of government or religious institutions that would later anchor families to a single settlement. Schools, churches, police, and medical facilities did not exist in most rural areas until later in the 19th century. Magistrates made annual visits, but residents largely governed themselves. Sometimes, they also performed religious ceremonies on their own, which might include presiding over weddings, funerals, christenings, and prayer meetings. With no church or school binding families to a single place of residence, they were free to move from one place to another as different resources became available at different times of the year.