Indigenous Relations with Europeans 1600-1900

The nature of Newfoundland and Labrador's economy limited direct interaction between Indigenous groups and Europeans for much of the 17th and 18th centuries. During this period, Newfoundland and Labrador served mainly as a seasonal fishing station for European crews engaged in the transatlantic migratory fishery. Most vessels arrived in spring and departed in August. Sustained contact between fishers and Indigenous people was rare and, because European governments had almost no interest in establishing permanent settlements on the island or in Labrador, they did not negotiate any land treaties with Indigenous groups, as was common elsewhere in North America.

As greater numbers of Europeans settled at Newfoundland and Labrador during the 19th century, they came into increased contact with Indigenous people. Although not all interactions were negative, they dramatically altered Indigenous society and cultural traditions. Over the long term, Christianity eroded shamanistic religions, English displaced Indigenous languages, and commerce with Europeans dominated subsistence economies. At the same time, direct government interaction with Indigenous groups was rare, and officials instead allowed missionaries and traders to administer laws, regulate trade, and distribute food and other forms of aid to Indigenous groups.

Indigenous Groups and the Migratory Fishery

The transatlantic migratory fishery operated at Newfoundland and Labrador from the 16th through the 19th centuries. During this period, four distinct Indigenous groups used land and resources at Newfoundland and Labrador – the Innu and Inuit in Labrador, and the Beothuk and Mi'kmaq on the island. Although each group had a distinct history of contact with Europeans, they shared in common an almost complete lack of interactions with government officials until the 20th century.

This was unusual, as colonial authorities elsewhere in North America often negotiated land-cessation treaties with Indigenous groups to acquire property for settlement, or for agricultural and other purposes. European governments, however, were much more interested in Newfoundland and Labrador's rich cod stocks than they were in its land resources and made little attempt to permanently settle the region until the 1800s. Colonial officials instead used coastal Newfoundland and Labrador as a base for the migratory fishery, making it unnecessary to appoint agents to negotiate treaties with Indigenous groups.

As European nations competed for control of lands in the New World, they often appointed agents to secure support or neutrality from Indigenous groups. French authorities in Nova Scotia, for example, became allied with the Mi'kmaq during the colonial period. In Newfoundland and Labrador, however, it was the nation with the strongest naval – not land – force that would gain supremacy, making it largely unnecessary for British, French, and other governments to seek help from Indigenous groups.

Although Indigenous people came into little formal contact with colonial authorities in Newfoundland and Labrador, they did have informal encounters with European fishers. Some interactions were positive and mutually beneficial, while others resulted in misunderstandings and conflict. A common source of tension was Indigenous people's use of abandoned European campsites and equipment during the fall and winter. After Europeans returned home each year, they left behind boats, cabins, flakes, stages, fishing hooks and other gear. The Beothuk and Inuit took nails, kettles, fish hooks, and other metal pieces from abandoned stations, often burning or destroying wooden structures in the process. Upon their return, many European fishers felt Indigenous people were stealing their property, which resulted in tensions and sometimes in violence.

Missionaries and Fur Traders

Christian missionaries and commercial trading companies regularly interacted with Indigenous groups in Newfoundland and Labrador, especially after the mid-1700s. Colonial officials often relied on mission workers and fur traders to administer the Indigenous population instead of appointing official government liaisons. Newfoundland and Labrador Governor Sir Hugh Palliser, for example, invited the Moravian Church – a protestant sect that worked with Inuit at Greenland – to establish mission stations at Labrador during the 1770s. Palliser hoped a Moravian presence would help curb mounting hostilities between the Inuit and Europeans.

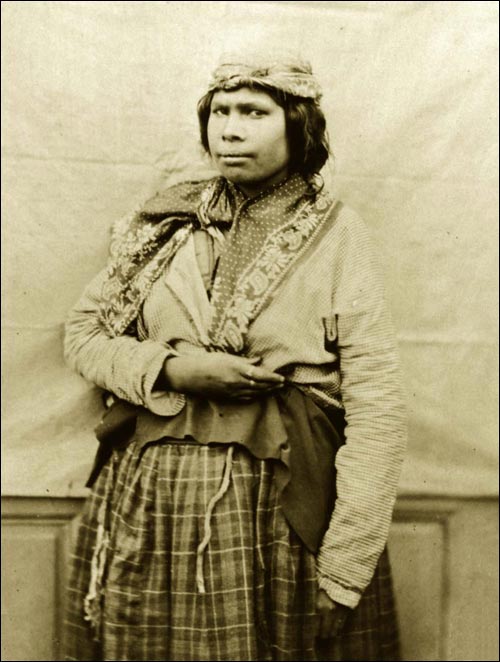

The Moravians opened their first station at Nain in 1771 and others quickly followed elsewhere in Labrador. In addition to providing the Inuit with religious, medical, and educational services, the Moravians took over all trade operations with the Inuit and forbade Europeans from entering mission grounds, which effectively ended hostilities between the two groups. Although mission workers sought to protect some aspects of Inuit culture – they taught reading and writing in Inuktitut and provided Inuktitut translations of the New Testament – they also promoted Christian ideals that undermined the Inuit belief system. Contact with European settlers in Labrador became increasingly common during the 19th century and it was not uncommon for European men to marry Inuit women; their descendents are today known as the Southern Inuit and Kablunângajuit people.

Commercial fur traders also operated out of Labrador, but dealt with the Innu people instead of the Inuit. Most prominent among these was the Hudson Bay Company (HBC), which established a post in central Labrador in 1831. Roman Catholic missionaries also visited Labrador trading posts during the latter half of the 19th century and came into contact with the Innu people. Both traders and missionaries acted as government intermediaries to the Innu, distributing state-issued food and clothing to needy families during the late 1800s – a task which government officials carried out on the island. In addition, missionaries served as schoolteachers for Innu children; they also objected to the Innu shamanistic religion and abolished many of its rituals.

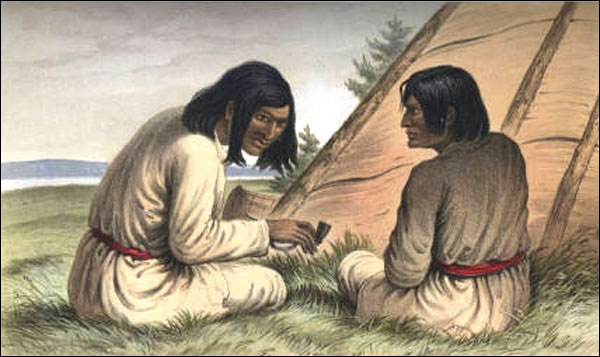

On the island, the Mi'kmaq people often traded furs with French or English settlers in return for guns, clothing, copper kettles, and other manufactured goods. Contact with European settlers became increasingly common during the 19th century and marriages, especially between Mi'kmaq men and European women, were not uncommon.

In contrast, the Beothuk largely avoided European contact. No substantial trade operations evolved between the two peoples and the colonial government made few attempts to establish relations – friendly or otherwise – with the Beothuk. Although Indigenous groups elsewhere in North America traded furs to Europeans for metal tools, the Beothuk were able to obtain nails, fish hooks, and other items by scavenging abandoned fishing stations each fall and winter, eliminating the need to engage in face-to-face negotiations with Europeans. The Beothuk also spent much of the year in interior regions of the island, which reduced any chance of contact with European settlers on the coast. As a result, no relations of any importance evolved between European settlers at Newfoundland and the Beothuk people.