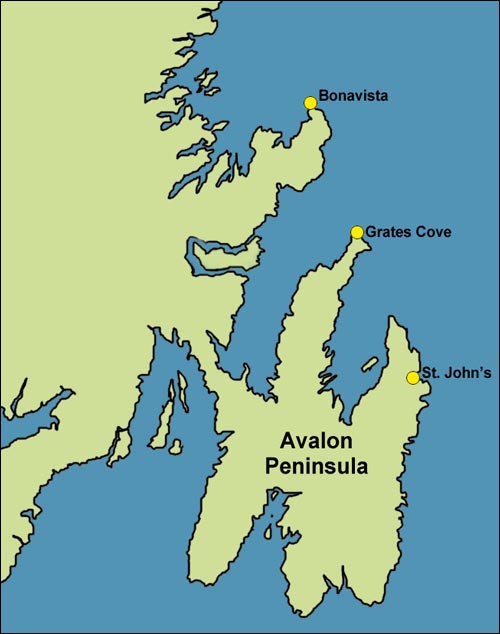

The Grates Cove Tradition

Grates Cove is a small community near the most northerly point of the Avalon Peninsula, settled during the late 18th century. Local tradition holds that John Cabot landed at Grates Cove on his first voyage to North America in 1497, and - a later addition - that on his second voyage he was wrecked nearby and died there, together with his son Sancius. The tradition is closely linked to the existence of a large rock bearing inscriptions which some claim were carved by Cabot himself. The "Cabot Rock" disappeared some time ago, taken away - it is said - by two men who arrived in a media van.

The Cabot Rock

The earliest mention of the tradition in print is in William Cormack's 1822 journal: "The Point of Grates is the part of North America first discovered by Europeans. Sebastian Cabot landed here in 1497, and took possession of 'The Newfoundland' .... He recorded the event by cutting an inscription, still perfectly legible, on a large block of rock that stands on the shore." (Cormack 1873, 9) The precise inscriptions are not mentioned, and Cormack does not say that he landed at Grates Cove. Nevertheless, this is evidence that an association between Grates Cove and the Cabots existed in the early 19th century. The reference to Sebastian rather than John Cabot reflects the commonly held assumption in Cormack's time that the father's exploits were those of the son.

It seems that during the 1897 celebrations to mark the 400th anniversary of Cabot's voyage there was virtually no mention of Grates Cove. Apparently Michael Howley, the Roman Catholic bishop of St. John's and a keen local historian, visited the community that year, but could not get near the rock. A fishing stage had been built over it, and the accumulation of offal made it unapproachable.

From Peter Neary and Patrick O'Flaherty, Part of the Main: An Illustrated History of Newfoundland and Labrador. (St. John's, Newfoundland: Breakwater Books, © 1983) 104. Courtesy of the Presentation Congregation Archives, Presentation Convent.

Other visitors followed. W.A. Munn, a Harbour Grace businessman and antiquarian, made a careful examination of the rock in 1905. But all he could find were graffiti dating from the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Cabot Rock found its champion later in the century. Leo E.F. English, a teacher and school inspector who became curator of the Newfoundland Museum in 1946 (now The Rooms Provincial Museum Division), took photos of the rock in 1927. He claimed that the photos showed the words "IO CABOTO", and parts of other names, among them "SANCIUS" and "SAINMALIA". English was convinced that "Cabot himself - or at least a member of his crew - engraved the names on that historic, fish offal covered rock ...." (English 1955)

The second aspect of the story - that Cabot died at Grates Cove - was added to English's claims in 1955. Professor Arthur Davies of the University of Exeter, apparently taking the authenticity of the rock for granted, put English's statements together with other evidence, and suggested in a most ingenious article that the rock's markings were associated with Cabot's second voyage in 1498, from which he did not return. A key point was that when Gaspar Corte Real took prisoner 50 Indians in eastern Newfoundland in 1502, one of them possessed a broken gilt sword of Italian origin, and another wore silver earrings of Venetian origin. Davies thought these had to be relics of the Cabot expedition.

He proposed that after fishing near Baccalieu, Cabot turned south to cross Conception Bay. The ship went down at sea, and "It may be that Cabot, his young son Sancius and some of the crew succeeded in reaching Grates Cove in the ship's boat. Cabot and Sancius certainly got ashore, alive or dead, for the ... sword points to Cabot himself and the Venetian earrings to the boy Sancius. "Once on land, they inscribed their names on the rock since others would be searching for them. " 'Sainmalia' could be the remnant of `Santa Maria save us' or some such expression." Soon after, Davies thought, the survivors must have been killed by Indians. (Davies 1955)

Davies had never visited Grates Cove. Those who did, failed to find what Leo English had seen, and his claims were criticised. Now that the rock itself is gone, we may never know whether English or his critics were correct.