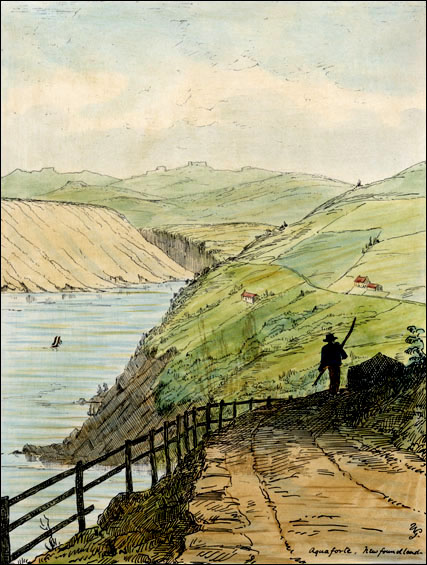

Eyewitness Accounts of Early Outport Life

Much of our knowledge of daily life in outport Newfoundland in the late 18th and early 19th century comes from the pens of visitors. They were typically missionaries, explorers, naturalists, and geologists whose work brought them to outlying communities not often visited by outsiders or even the local government. Although their observations of daily life are often brief and incomplete, the picture they provide is important if only because most outport residents in this period were illiterate.

Below are excerpts from several texts written by visitors to Newfoundland and Labrador in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. They provide a glimpse into the way of life of settlers during that time.

About the Authors

Anspach, Lewis Amadeus (1770-1823): Born in Geneva, Switzerland, Anspach worked in Newfoundland as a teacher and missionary with the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel from 1799 until 1812. His book, A History of the Island of Newfoundland, was published in London in 1819.

Banks, Sir Joseph (1743-1820). The English naturalist and botanist visited Newfoundland and Labrador in 1766 to study its natural history. Although his journal focuses largely on the colony's flora and fauna, it also provides brief descriptions of the people and communities he encountered.

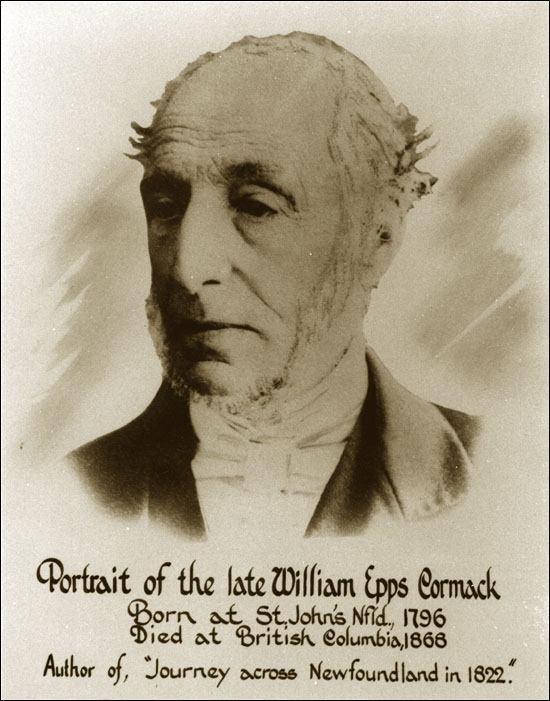

Cormack, William Epps (1796-1868): The Scottish-Canadian explorer was the first European to walk across Newfoundland's interior. On 5 September 1822, Cormack left Smith Sound, Trinity Bay. He arrived at St. George's Bay on 4 November.

Jukes, Joseph Beete (1811-1869): An English geologist, Jukes was appointed geological surveyor 1839. He spent 16 months exploring the island, and wrote an extensive report.

Tucker, Ephraim W. (ca. 1819-1864): In 1838, Tucker's physician suggested he should take a sea voyage to restore his ailing health. The American clergyman departed Boston in May and spent five months sailing around the coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador, where he also visited numerous communities.

Wilson, William (1799-1869): An English-born Methodist missionary, Wilson arrived at Harbour Grace in 1820 and spent the next 14 years on the island. He worked in numerous communities, including Bonavista, Burin, Lower Island Cove, and Grand Bank.

Wix, Edward (1802-1866). Born in England, Wix was ordained a Church of England clergyman in 1825. He completed a six-month missionary tour of Newfoundland's eastern, southern, and western coasts in 1835. His journal was published the following year in London.

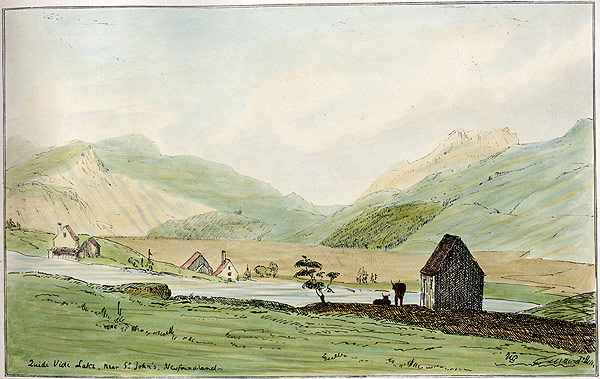

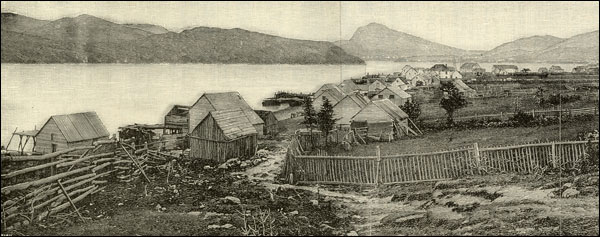

A Typical Newfoundland Outport: 1839

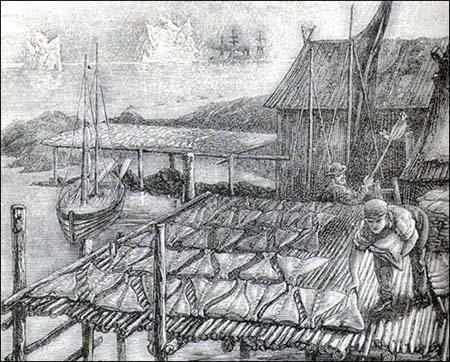

The first thing that strikes a stranger on entering a harbour in Newfoundland [in 1839] is the abundance of what are called the fish-flakes and stages, together with the wooden wharfs and the great dark red storehouses. Jukes, Vol. 1, 222

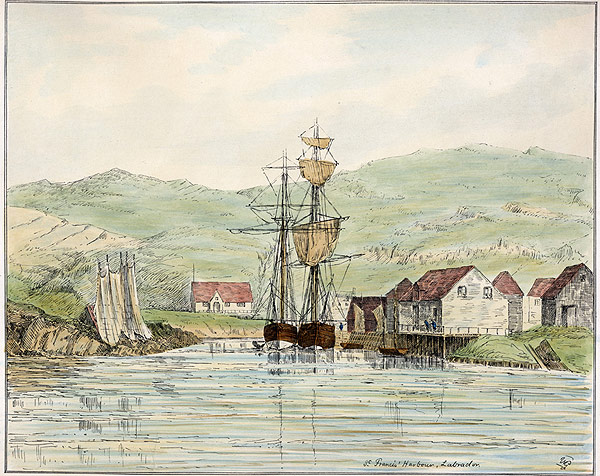

Now if the reader will picture to himself, in addition to all this, a few brigs and schooners at anchor in the harbour, and a multitude of small fishing boats, varying in size from a two-oared punt to a half-decked schooner-rigged craft of ten or fifteen tons;-a broken rocky shore, with a stunted wood and little patches of cleared and cultivated garden-ground;-one or two large-sized wooden houses, painted white, belonging to the merchants, and a number of unpainted wooden cottages scattered here and there at all possible angles with each other, perched upon rocks and hidden in nooks, belonging to the fishermen:-if, I say, he can associate all these things in his fancy, he will have before him a tolerably correct notion of a Newfoundland settlement. Jukes, Vol. 1, 224-225

Of course, in the larger places, more especially in St. John's, these elements are overpowered and thrown into the background by others of more imposing character. Large stone houses, good-sized churches, chapels, and court-houses: shops built of wood and painted white, a tolerably regular street, and a road or two, mark the seat of greater wealth, and a more numerous population. Even in St. John's, however, fish-flakes are by no means entirely absent, though they are confined to the south side of the harbour, and to a small nook, bearing the euphonious appellation of Maggoty Cove. Jukes, Vol. 1, 225

Winter Homes

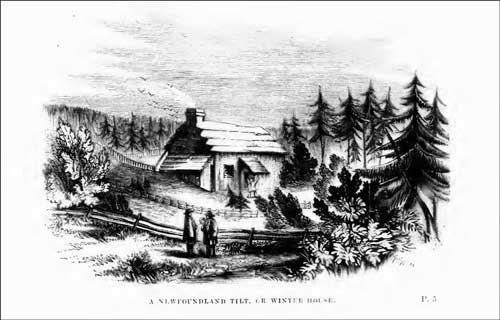

We caught sight of a head of chips of wood in a cove [at Trinity Bay, 1839] on the right hand, which the men said was probably near a winter-house or tilt. We made for it accordingly, and found a path leading in about 50 yards to a very good "tilt." This was formed of trunks of trees placed upright on the ground close together, with larger ones for the corner-pieces, and a good strong gable-end roof formed of a frame of roughly squared beams. The corner pieces and beams were nailed together, and the rest driven in tight with wedges wherever necessary. The interstices of those trunks which formed the walls were filled up with moss tightly rammed between them; and the roof was covered by long strips or sheets of birch bark, laid tile-like over one another, and kept down by poles or sticks laid across them. A space for a door is left in the middle of one side, and a fire-place is built up with stones and boulders against one end, over which is a space in the roof and some boards nailed together for a chimney. In this way a tolerable room, twelve or fourteen feet by eight or ten, is formed, sufficiently compact to keep out wind and weather to a certain extent. Jukes, Vol. 1, 69-70

December 13, 1822: The residents here [at Ramea Islands on Newfoundland's south coast], as at St. George's Bay and at most of the north and west harbours of the Island, have both summer and winter houses. They retire to the residences at the shore, which are exposed to every inclemency of the weather, being very great. They sometimes remove to a distance of 30 miles and even farther to the sequestered woods at the heads of bays and harbours, and on the banks of rivers, taking with them their boats, furniture, and provisions, and re-appear at the coast in the month of April. (Cormack qtd. in Howley 166)

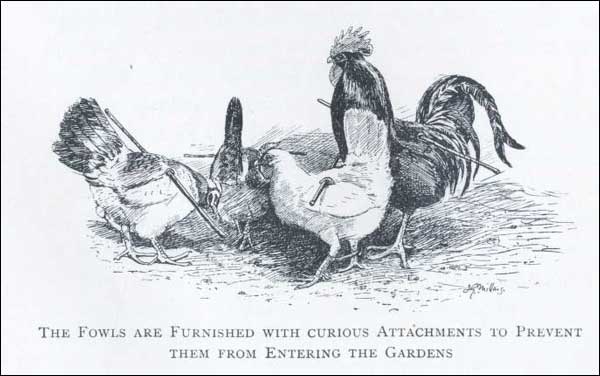

[1799-1812] They call tilts temporary log houses, which they erect in the woods to pursue their winter occupations. Tilt-backs or linneys, are sheds made of studs and covered either with boards or with boughs, resembling the section of a roof, fixed to the back of their dwellings towards the wind. They have only one fireplace in a very large kitchen partially enclosed with boards, and having within a bench on each side, so as to admit eight or ten persons. Under these benches they manage convenient places for their poultry, by which means they have fresh eggs during the most severe winters: these chimneys are likewise by their width extremely fit for the purpose of smoking salmon and other kinds of fish or eatables, as the only fuel used in them is wood, which is found at no great distance. Anspach 468

"My eyes, which have been much tired by the glare of the sun upon the snow, and by the cutting winds abroad, are further tired within the houses by the quantity of smoke, or "cruel steam," as the people emphatically and correctly designate it, with which every tilt is filled. The structure of the winter tilt, the chimney of which is of upright studs, stuffed or "stogged" between with moss, is so rude, that in most of them in which I officiated the chimney has caught fire once, if not oftener, during the service. When a fire is kept up, which is not unusual all night long, it is necessary that somebody should sit up, with a bucket of water at hand, to stay the progress of these frequent fires; an old gun-barrel is often placed in the chimney corner, which is used as a syringe, or diminutive fire engine, to arrest the progress of these flames; or masses of snow are placed on top of the burning studs, which, as they melt down, extinguish the dangerous element. The chimneys of the summer-houses in Fortune Bay, are better fortified against the danger, being lined within all the way up with a coating of tin, which is found to last for several years." (Wix 64-65)

Summer Homes

"On arriving at Bloody Bay main brook we found a very decent man named Stroud, with his wife and seven daughters, the oldest not more that twelve years. He was the only summer resident in the bay, except one old man, a cooper, who made casks for the salmon. Stroud attended to the salmon fishery, which belonged to Messrs. Brooking and Garland, from whom he received regular wages, and a dollar for every tierce of salmon he caught. He had this summer caught forty-six tierce besides those consumed by his family. This was reckoned a very great catch for the mouth of one river. He had a comfortable house, a few cattle, and several very pretty little cleared spots or gardens, in which grew abundance of excellent potatoes, cabbages, greens, and turnips. The flat land on each side of the brook is half a mile wide and is of good quality. Deer and game of all sorts are very abundant at the proper seasons." (Jukes, Vol. 2 103-104)

"The common dwellings consist only of the ground-floor, or at most of one story: the materials, except the shingles, are the produce of the Newfoundland; the best sorts are clapboarded on the outside; others are built of logs left rough and uneven on the inside and outside, the interstices being filled up with moss, and the inside generally lined with boards planed and tongued. This filling with moss the vacancies between the studs to keep out the weather is there called chinsing. The floors are sometimes made of boards planed and tongued and sometimes of longers or poles nailed top to but." (Anspach 467-468)

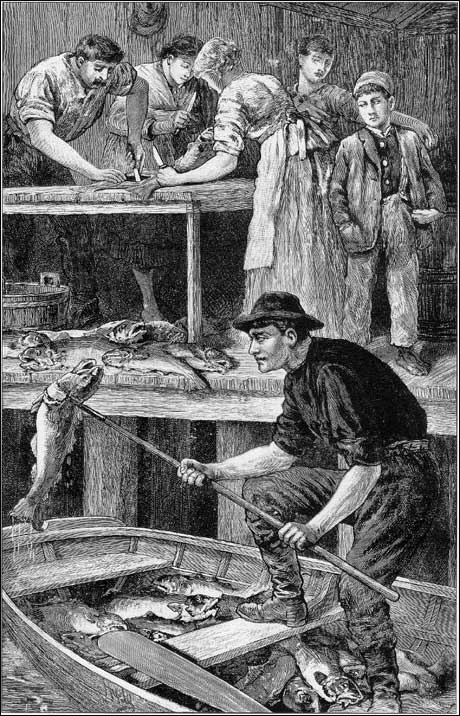

Activities and Home Life

"…We found only the woman and children at home, the man having gone down to fish about Placentia. They managed the cows and the salmon-nets. One of the latter was placed at the mouth of the brook, and one a mile or two up; and they told me that last year they had caught six tierce of salmon. These varied in value from 3l. to 6l. currency, so that the wife was enabled to get 20l. or 30l. every summer by her own exertions, independent of the results of her husband's cod-fishing, which would probably be as much more. As they, of course, paid no rent for either house or land, and had wood for firing and boat-building at command, they were well off. To counterbalance these advantages, however, they had no fresh meat unless when the man shot a deer, and had to fetch their bread, salt, pork, tea, sugar, and every article both of clothing and food, from Placentia, or some other distant merchant's store, where they necessarily paid high prices from the want of competition and the nature of the trade. We got here some fresh milk and butter, and while we were strolling about, the husband's boat came "goose-winged" up the bay before a fresh breeze, and my men got what they enjoyed more than even salmon and milk, namely, some news from Placentia and St. John's." (Jukes Vol. 1, 77-78)

"The inhabitants of Bonaventure, about a dozen families, gain their livelihood by the cod fishery. They cultivate only a few potatoes, and some other vegetables, which were of excellent quality, amongst the scanty patches of soil around their doors; obtaining all their other provisions, clothing, and outfit for the fishery, from merchants in other parts of Trinity Bay, or elsewhere on the coast, not too far distant, giving in return the produce of the fishery, viz., cod fish and cod oil. …The merchants import articles for the use of the fisheries from Europe and elsewhere to supply such people as these, who are actually engaged in the operations of the fishery. The whole population of Newfoundland may be viewed as similarly circumstanced with those of Bonaventure." (Cormack qtd. in Howley 133)

"There is a fur trading establishment situated in the harbor [Bonne Bay], owned by a wealthy Englishman, from whose little shop three hundred families of the inhabitants in Newfoundland are annually supplied with articles of clothing, salt, &c., in exchange for the furs which they bring in during the spring and fall. The fisheries, also, furnish the inhabitants with other means of supplying their wants; and the exports of Newfoundland find their way into remote corners of the earth. Their furs go to England, their cod-fish to the West-Indies and South America, their herring and salmon are sent to Grand Cairo and Jerusalem. …There are only forty inhabitants living at this place, and at Rocky harbor, which is situated down near the mouth." (Tucker 33)

"They are extravagantly fond of the canine race-and the noble animal known as the Newfoundland dog, may be said to be almost necessary to their existence. Every family has one or more of them. He is an inmate of the hut, and fares almost as well as the children of the family. Whenever the little ones go to their sports, the dog accompanies them, watches them while at play, and escorts them safely home. Should one of the little urchins fall into the water, the dog will rescue him from drowning; and the habits and services of the faithful animal endear him to every inhabitant of the island." (Tucker 68-69)

"The snow begins generally in November; and, in January the frost is so intense that it is hardly possible to be long out of doors without risk of serious injury to the extremities Most houses have very large stoves placed in the centre whence flues pass to the other apartments. Various other precautions are taken against the weather such as double doors and double windows in the houses and furs or other very warm coverings for the body." (Anspach 345)

"The natives of both sexes are equally remarkable for their ingenuity and industry. The women, besides the very valuable assistance which they afford during the season for curing and drying the fish, generally understand the whole process of preparing the wool from the fleece, and of manufacturing it by knitting into stockings, caps, socks, and mittens: their worsted stockings are strong and well calculated for the climate." (Anspach 468-469)

"At the third Barrisway, or Crabs, [near Port-au-Port on the island's west coast] I found three families, who, like those of the other settlements, were most industrious, moral, cleanly people. They are of Jersey extraction, principally mixed with emigrants from agricultural districts in the west of England. …They have some of the best land in the island, along the shore and in their rear …They live here, indeed, entirely on the produce of the soil, and of the cattle which they keep, and they live well. They are so far independent of the merchant, that they never apply to him for butter, pork, or beef. Indeed, if they could only find a market for their produce, they could rear more cattle and vegetables, and could cure more meat that their families require. There is no other part of Newfoundland like it. All the people of this bay prosecute the salmon fishery; this is generally very lucrative, as collecting furs also is in the winter." (Wix 187-189)

Food

"Late in the fall the potatoes are dug out and secured in cellars under ground. This valuable root is frequently injured by the early frosts before it has been housed, as well as in the cellars, during the winter, if the least damp or cold air reaches them. Even in the most favourable seasons the stock of potatoes raised in the island is so far from adequate to the consumption of the inhabitants that early arrivals of vessels in the spring are expected with great anxiety for fresh supplies of that commodity.

Turnips, parsnips, peas, beans, radishes, common small salad lettuce of various kinds, and sorrel, succeed very well in the gardens, and form an important part of the "luxuries" of that country. Even the common dandelion is most eagerly sought after in the spring, as a substitute for the greater delicacies of the fine season. Melons have been attempted with some success in hot houses: cucumbers are raised with less difficulty; and fine hops with the greatest facility.

Red, black, and white currants, gooseberries, and strawberries grow there in the greatest perfection; a smaller kind of the latter fruit grows spontaneously among the rocks and in the woods; raspberries grow any where. The cherries are excellent, but only of one kind usually known by the name of Kentish cherries. Damascenes, or damsons grow in abundance on handsome low trees, but seldom come to complete maturity. The plains throughout the whole island are covered with low bushes which bear a variety of wild berries." (Anspach 360-361)

"Ducks, geese, and common poultry are easily reared; turkeys succeed likewise, but with much greater trouble and expense: where supply of fresh meat is so irregular and scanty as it is in most of the inhabited parts of Newfoundland, these afford a valuable addition to the comforts of a family. When allowed a warm station near the fire place the hen will lay eggs during the most winters." (Anspach 389)

"Several old Bedlamer seals had been already killed here [New Harbour, Trinity Bay], which, with the sea-birds which were now very numerous, supplied the inhabitants with very acceptable provisions after the scarcity of a long unbroken winter." (Wix 22)

"After having said so much about Fishing it will not be improper to say a little about the Fish that they catch & of the Dish they make of it Calld Chowder which I believe is Peculiar to this Country tho here it is the Chief food of the Poorer & when well made a Luxury that the rich Even in England at Least in my opinion might be fond of It is a Soup made with a small quantity of salt Pork cut into Small Slices a good deal of fish and Biscuit Boyled for about an hour unlikely as this mixture appears to be Palatable I have Scarce met with any Body in this Country Who is not fond of it" (Lysaght Banks 137)

Character of Inhabitants

"…the Newfoundlanders are simple, honest, industrious, goodnatured and hospitable people, and have the virtues of all hardy races exposed to the toils and dangers of an adventurous life. Some of them are, no doubt, fond of rum; but though, during Christmas, or in holiday times, they may occasionally be "fou for weeks thegither," the mass of the people are not habitual drunkards. Many are tee-totallers of old standing. The Roman Catholic part of the population, more especially, have an old custom called "cagging," taking a vow, that is, before the priest, not to touch rum or spirits for a year or two, or for their whole lives, or while they are on shore, &c., and these vows are scrupulously adhered to." (Jukes, Vol.1 238-239)

"…I can only give my advice to any one who wishes to lead the life of a traveller to commence with this country, in order to get well accustomed to rough living, rough fare, and rough travelling, and to get rid of all delicate and fastidious notions of comfort, convenience, and accommodation he may have acquired by journeying in England. I must add, however, that so far as the inhabitants are concerned, under a rough exterior he will meet with sterling kindness and hospitality." (Jukes, Vol. 2 173)

"We had no sooner reached the shore, than the inhabitants came huddling down to see their unfrequent visitants. After making numerous inquiries, and ascertaining the particulars of our voyage, they welcomed us to their fire-sides. We accompanied them up to one of their huts, surrounded by the tall grass upon the strand, and near the water's edge. We found the inhabitants full of animation, boastful of their hunting and fishing exploits, and extremely inquisitive about every thing relating to the United States. They expressed a strong desire to leave their bleak, inhospitable climate, and barren mountains, to seek a better country - but wanted the means. They would gladly exchange their hunting and fishing, for the cultivation of a fertile soil, the advantages of which to the American husbandman they seemed to comprehend." (Tucker 31-32)

"In their families and intercourse with one another, these people are kind, companionable, and benevolent. In cases of sickness, or difficulty of any kind, they will go miles to watch by the bedside of a suffering friend, or to aid him in any time of want or peril. The stranger approaching their habitations, is always welcomed with kindness, and if his deportment among them is exemplary, they urge him to prolong his stay, and kindly offer to instruct him in all the mysteries of fishing and the chase." (Tucker 68)

Special Occasions

"I accompanied him in the evening to a wedding at a fisherman's house close by. The company, consisting of young men and women with a few of the seniors, assembled about nine o'clock, and sat round the room drinking grog for some time. Presently a fifer struck up a tune and reels and jigs began. There was much bustling of women in and out of a back room; and about half past ten the bride was said to be ready, the music ceased, a table was brought forward, the priest put on his scapular, and the bride and bridegroom came forward and knelt before the table. The priest opened his book, asked them the usual questions in English, and rapidly read a number of Latin prayers and the ceremony was completed. Instantly there was a struggle among the young men around for the first kiss; but as the bride was not yet off her knees, and the bridegroom was kneeling beside her, he had the best chance, and won accordingly. A plate of cake was next produced and put upon the table: the bride and bridegroom came forward, took a piece of cake, and deposited several dollars on the table before the priest. Each one in the room then came forward and took a piece of cake, leaving a dollar before the priest, who stood behind the table thanking them as they came up." (Jukes, Vol. 2 28-29)

"Marriages and christenings usually take place either at the fall, when the fishing concerns are at an end and all accounts are settled, or sometimes in the spring, previous to the resuming of those occupations. They are seasons of festivity, celebrated with good cheer and the firing of guns." (Anspach 470-471)

"A wedding in an out-harbour was quite an affair. Neither a licence nor the publication of banns was required for the performance of marriage; and frequently the minister knew nothing about it, until the party arrived at the mission-house. The ceremony was usually performed in the church, when the flag would be hoisted, at which signal almost the whole community would assemble to see "the couple made happy." As soon as the party came out of church, a number of guns would be fired over the heads of the bride and bridegroom, and also over the head of the parson, as a salute, which would be occasionally repeated until we reached the house. Here the invitation would be given to dinner, which would sometimes be so general as to include all hands. At the dinner there were great profusion and drinking, as was then the custom; but rioting and disturbance of the public peace were not known. It was not the habit of the Newfoundlanders to insult or annoy any person; much less would they do so in the presence of their minister." (Wilson 355)

"Their funeral ceremonies are generally conducted with some parade, and attended by a large concourse of people, in proportion to the regard entertained by the public for the deceased. The clergymen of the place or district, both Protestant and Roman Catholic, meet at the house where the corpse is deposited, with the relations and friends, and there partake with them of a small collation, consisting of bread and cheese, seed-cake, wine, spirits, and tea. The procession, preceded by the clergy who march before the corpse, proceeds to the place of burial attended by the relatives two and two, and followed by the friends without any order. After the service has been performed and the ceremony is concluded, the procession returns in the same order to the house of the deceased and there separates." (Anspach 471)

"The practice of "waking the dead" is pretty general in Newfoundland, particularly among the natives of Irish extraction, who, in this respect, most faithfully adhere to the usage of their fathers in every point, as to crying most bitterly, and very often with dry eyes, howling, making a variety of strange gestures and contortions expressive of the violence of their grief and also as to drinking to revive their spirits and keep themselves awake." (Anspach 472-473)