Geological Landscape

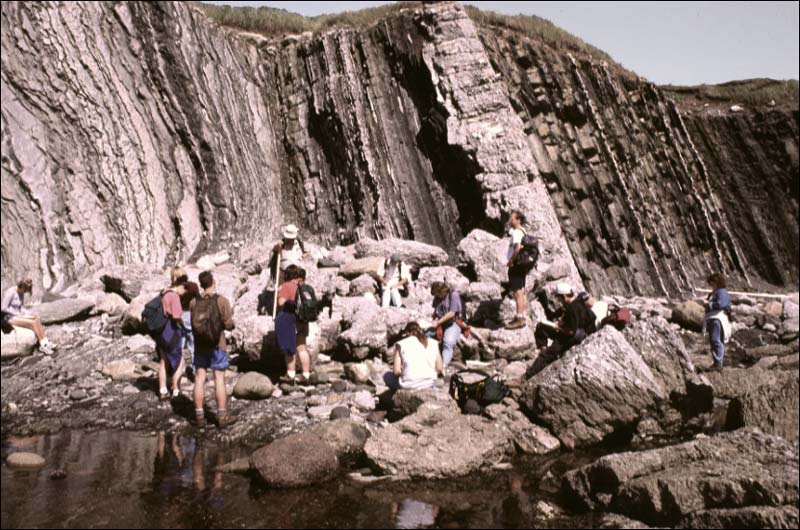

Newfoundland and Labrador has a world class geology. Earth scientists from all over the globe visit the province to study the record of the earth's evolution preserved in its rocks. Not only does it have some of the oldest rocks in the world, but it also has some unusual sequences of rocks which tell a fascinating tale of colliding continents and disappearing oceans in the geological past. Gros Morne National Park, in western Newfoundland, was declared an UNESCO World Heritage site in 1987 to recognize and preserve its unique geological landscape which has been described as the 8th Wonder of the World.

The mineral resources of Newfoundland and Labrador are a direct product of its geological history. The discovery of a major ore deposit at Voisey's Bay, Labrador, in 1993 and the successful development of the Hibernia offshore oil field highlight a long tradition of mining and resource use dating back to prehistoric time when the Maritime Archaic Indians quarried Ramah chert in northern Labrador and traded it throughout the Atlantic provinces and states.

Earth's Changing Surface

The Earth's solid surface is a restless jigsaw of abutting, diverging, and colliding slabs called tectonic plates. How plates behave forms the subject known as plate tectonics. It is an important key to understanding why continents collided in ancient Newfoundland and Labrador.

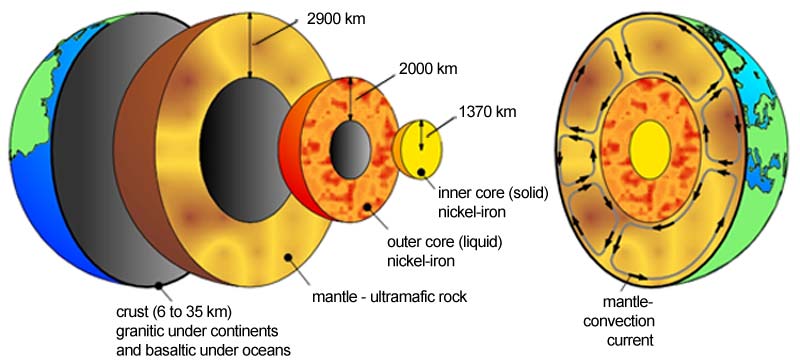

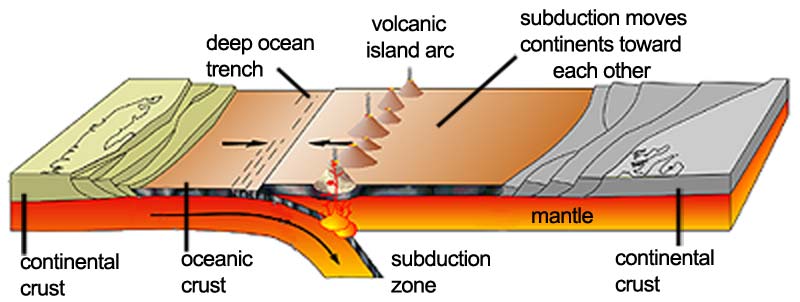

A slice through the Earth reveals a layered structure: a central metallic core surrounded by a thick mantle and a thin outer crust.

The mantle is solid, but over very long periods of time most of it behaves like plasticine and flows. The temperature difference between the top and bottom of the mantle causes a circular flow called convection. The uppermost mantle and crust form an outer shell of rigid plates. The plates, and the continents they contain, move across the Earth's surface on the convection currents.

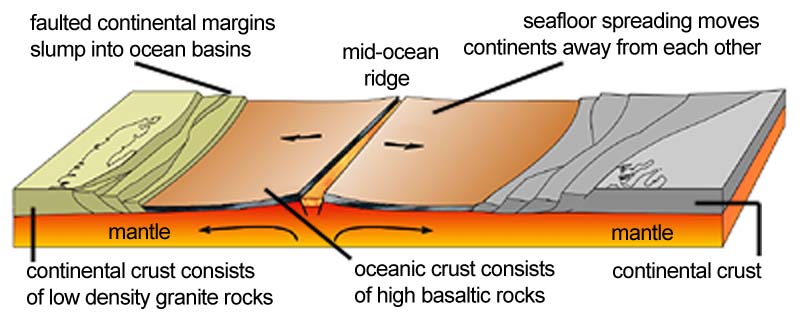

Plates grow by the addition of new rock from the mantle at mid-ocean ridges, where the convection currents rise. The volcanic island of Iceland sits on top of the Atlantic mid-ocean ridge. Plates are destroyed when they are carried down into the mantle at subduction zones, such as the one off the coast of British Columbia. In some places, the plates simply slide past each other along huge faults, like the San Andreas Fault in California. Modern plate movements have parallels in the distant past when the same processes built the Island of Newfoundland.

At mid-ocean ridges, rising convection currents melt mantle rock to form magma, which then collects in magma chambers beneath the ridges.

Movement in the mantle cracks the overlying crust, allowing the magma to escape and build volcanoes on the sea floor. Each time the crust cracks, the rocks on either side of the ridge are moved a small distance sideways to make room for the new volcanic rock. Repeated cracking gradually moves old volcanoes away from the hot, active ridge area, and they become buried under layers of sediment.

When a plate descends into the mantle at a subduction zone, part of it melts in the hot interior of the Earth. The melted rock erupts on the surface as a line of volcanoes.

If subduction is at the edge of a continent, the volcanoes form mountains; Mount St. Helens in the northwest United States is an example. If the subduction is far from a continent, the result is a chain of volcanic islands, known as an island-arc. Many of the islands in the Caribbean and the western Pacific Ocean were formed in this way.

Ocean crust and mantle are easily subducted because they are made of heavy basalt, gabbro and ultramafic rock, which "sink" into the mantle. Continent crust, however, is made of lighter rocks like granite and it "floats" on the mantle, instead of being subducted. When continents collide, rocks are crumpled into great folds and large slabs of crust are pushed on top of each other to form mountains. The Himalayas were built during the past 60 million years by the collision of India and the rest of Asia. The Appalachian Mountain system, which extends into the island of Newfoundland, was formed in a similar way 400 million years ago, but it has since been worn down by erosion.