The Roman Catholic Church

Although the earliest Roman Catholic presence in Newfoundland is unconfirmed, by the 16th century priests sometimes accompanied European explorers and fishermen who came to Newfoundland. The first known Roman Catholics who settled on the island were colonists who came to Lord Baltimore's Ferryland colony in the 1620s. Father Anthony Pole (alias Smith) came to the colony in 1627 and was the first Roman Catholic priest to reside in British North America. The Ferryland colony was not intended solely for Catholics, and Anglican priests also served these early settlers. However, this initial presence of Roman Catholicism in Newfoundland was short-lived as the colony was abandoned in 1629.

Roman Catholic Presence in Newfoundland

French colonial activity brought more substantial Roman Catholic institutions to Newfoundland. The French colony at Plaisance (Placentia) was served by a young priest in 1662, although he was murdered in a mutiny that same winter. Numerous priests served as missionaries and chaplains, and by 1687 Catholic chapels had been established in the settlements at Argentia, Pointe Verde, St. Pierre, and Harbour Breton among others. The See of Québec comprised all the French possessions in North America and in 1689 the Bishop, Jean St. Vallier, visited Plaisance. The Bishop formally established the first Newfoundland parish under the guidance of Récollet priests from Québec, including Joseph Denys and Sixte Le Tac who had travelled to the island with the bishop. Denys, and a lay brother, Claude Pelletier, served in Newfoundland for several years ensuring the growth and consolidation of the newly-formed parish. By the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 the French colonies in Newfoundland were transferred to British control. Many of the French Newfoundlanders emigrated to Cape Breton and elsewhere in North America where French authority persisted.

The arrival of large numbers of Irish immigrants during the 18th century reinforced the Roman Catholic presence in Newfoundland. By the 1780s, the Irish constituted close to half of the permanent inhabitants of the island. Most of them settled between Placentia Bay and Conception Bay, thus establishing the strong Irish Catholic presence that has since characterised the Avalon peninsula.

British rule in Newfoundland created difficulties for the Roman Catholics. A 1729 decree granted a liberty of conscience to all 'except Papists,' and the governorship of Richard Dorrill in 1755 was a particularly harsh period, since he enforced fines, deported Catholics, and advocated the destruction of Catholic property. However, by 1779 full religious liberty was granted to all people in Newfoundland.

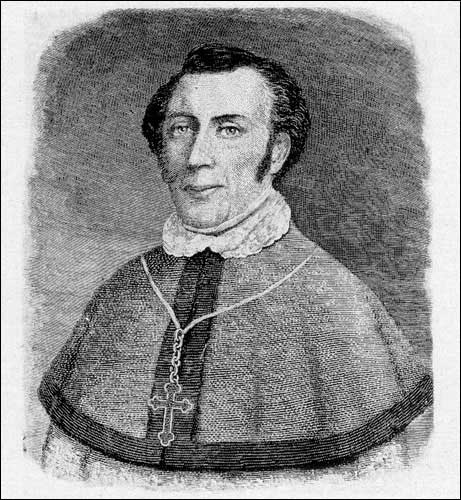

In 1784 Pope Pius VI recognised Newfoundland as an independent ecclesiastical territory, removing it from the authority of the Vicar-Apostolic of London and placing it under the jurisdiction of the Irish Franciscan priest James Louis O'Donel. Newfoundland was thus the first English-speaking jurisdiction established by the Vatican in British North America. O'Donel arrived in 1784 with Father Patrick Phelan, who was to serve the parish at Harbour Grace. O'Donel helped to found new parishes in Placentia and Ferryland and his authority and energy encouraged the Vatican to elevate the Prefecture of Newfoundland to a Vicariate Apostolic in 1796. O'Donel, who was consecrated bishop in September 1796, was thus the first Roman Catholic bishop in North America outside Québec. The Catholic Church in Newfoundland retained significant ties with Ireland.

The Irish uprising in 1798 created tensions which culminated in 1800 with the revolt of United Irish sympathizers in the St. John's garrison. O'Donel's authority ensured that this unrest did not spread. However his policy of appeasement and pacification contrasted with the increasingly independent attitude of subsequent bishops. Irish migration to Newfoundland peaked around 1815, and the activity of priests throughout the island brought new converts to the Church. Although the Roman Catholic Emancipation Act was passed by the British Parliament in 1829, restrictions on Catholics in public life persisted in Newfoundland even after the introduction of representative government in 1832.

Advancements in the Roman Catholic Church

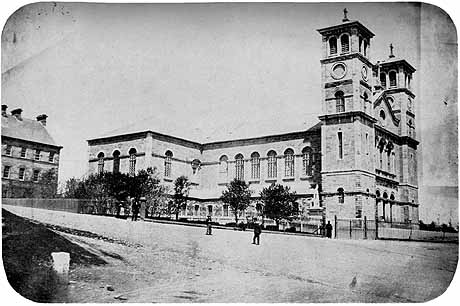

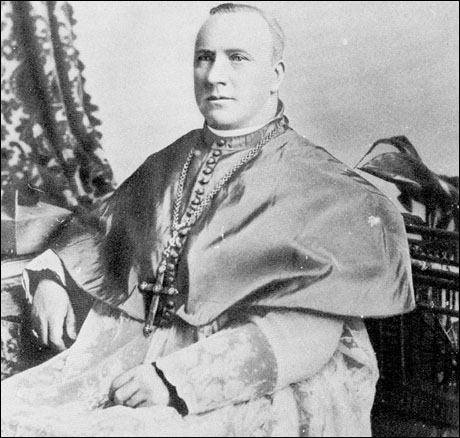

The episcopate of Bishop Michael Anthony Fleming began in 1829. Under his authority the Roman Catholic Church moved away from its missionary roots as new parishes were established and existing parishes continued to grow. Fleming introduced the Presentation Sisters and the Sisters of Mercy, and began the construction of the Cathedral (now the Basilica) of St. John the Baptist in St. John's. The cathedral was not finished until 1855, under Fleming's successor Bishop John Thomas Mullock.

In 1843 Catholic and Protestant schooling was effectively separated, reflecting the educational divisions that culminated in a fully denominational school system in 1874 and which lasted until the 1990s. It was during Fleming's episcopate that the Vicariate of Newfoundland became a diocese in 1847. This growing independence was further reinforced with the introduction of responsible government in 1855, which the Church had strongly supported.

In 1856 the diocese of Newfoundland was divided between St. John's and Harbour Grace. St. John's fell under the authority of Mullock, while the diocese of Harbour Grace, which included Labrador, was led by John Dalton. The west coast became a separate prefecture-apostolic in 1870. The Catholic population there differed in that there were relatively few Irish Catholics, and the population was comprised of Acadians, Bretons, Normans, St. Pierrais, Mi'kmaq and Scots. Since this region was part of the French Treaty Shore and was subject to restrictive treaties, Catholic priests often served as important representatives of local interests and needs.

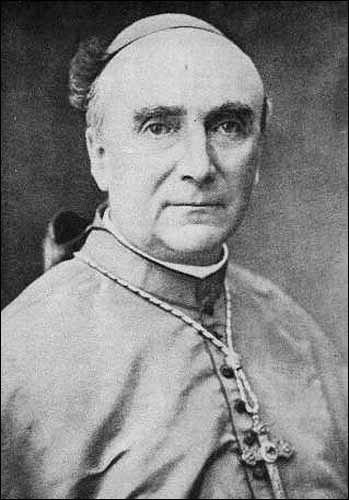

The first native-born bishop, Michael Francis Howley, first served as vicar apostolic of Western Newfoundland, and in 1894 was transferred to St. John's. Howley became the first archbishop when Newfoundland was declared an independent ecclesiastical province in 1904.

Archbishop Edward Patrick Roche, who succeeded Howley in 1914, was to guide the Roman Catholic Church through the significant changes that took place in Newfoundland in the first half of the 20th century. He strongly opposed any changes to the denominational education system, and during the 1948-9 debates over confederation with Canada, supported a return to responsible government.

As new population centres emerged, the seat of the diocese of St. George's was transferred to Corner Brook, and the headquarters of the Harbour Grace diocese was transferred to Grand Falls. Similarly, Labrador was established as a separate Vicariate in 1946. After 1949, Newfoundland Catholicism under the Canadian-educated Archbishop Patrick James Skinner (1950-1979) gradually drew closer to the Catholic Church in Canada, and increasing numbers of Newfoundland priests were educated at Canadian seminaries.

Social Changes and Scandals in the 20th Century

The Church attempted to address a number of social and cultural changes in Newfoundland society following Confederation, and considerable success was achieved in expanding and making available high school education. The Church reached the zenith of its social and cultural influence with the visit in 1984 of Pope John Paul II.

By the late 1980s, however, investigations of sexual abuse of children by clergy severely curtailed the credibility of the Church's leadership, resulting in the resignation of Archbishop A.L. Penney in 1991. Faced with diminished numbers of clergy, the Church under the leadership of Archbishop James H. Macdonald engaged in a process of renewal by involving greater numbers of lay members in active ministries.

With less success, since the early 1990s the Church has also sought to defend its prerogatives in denominational education, which were embodied in Term 17 of the Terms of Union with Canada. Following two provincial referenda on education in 1996 and 1997, Term 17 was revised by the Government of Canada and the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, and religious denominations no longer had a right to state funding for denominational schools.