Bishop James Louis O'Donel (1737-1811)

In the autumn of 1784, in response to the invitation of several well-to-do St. John's and Waterford merchants, the Franciscan priest James Louis O'Donel, came to St. John's and formally established the Roman Catholic Church in Newfoundland.

Early Life

O'Donel had been born in 1737 to a well-to-do farming family in Knocklofty, County Tipperary, Ireland. He and his brother Michael were sent to a private tutor, then to nearby Limerick for an education in the classics, before both entered the Franciscan order.

During the 18th century, Ireland laboured under the British-enacted penal laws, which limited Roman Catholics in various ways, particularly the spread of institutional Catholicism. According to Daire Keogh, this included compelling Catholic priests to appear before courts, register their names, addresses, parishes, dates and places of ordination, and the name of the ordaining prelate. Educational restrictions were also among the first to be put in place; in 1695, it was enacted that "no person of the popish religion may publicly teach school or instruct youth", while other provisions were aimed at restricting the flow of Irish students travelling for education to the European continent.

By the 1760s, however, the penal laws were irregularly enforced in Ireland, and James Louis O'Donel was sent to the college of St. Isidore's in Rome, the Irish Franciscan ultramontane stronghold in Rome, to be educated for the priesthood. He was ordained there in 1770. Beginning with O'Donel, Newfoundland Catholicism maintained strong ties with St. Isidore's for the next century. Into the late 1830s Bishop Fleming sent requests to the friars there for masses his congregation wished to have said, as well as what must have been somewhat exotic fare for Italy, tierces of smoked Newfoundland salmon for the friars. In 1848 Fleming's successor John Thomas Mullock was consecrated Bishop of Newfoundland in St. Isidore's College chapel.

Following his ordination, O'Donel's career followed a meteoric trajectory in the Church. During the mid-1770s he taught philosophy and theology at Prague, Czechoslovakia, returning in 1777 to Ireland to become Prior of the Franciscan monastery at Waterford, where he became a popular preacher. Two years later, he was elected Provincial of the Irish Franciscans.

By 1783 in Newfoundland, some legal obstacles to religious liberties for Roman Catholics had been removed and liberty of conscience was proclaimed. O'Donel, a popular preacher, was selected for his ability to minister to the Irish migrants and settlers in their native Irish Gaelic tongue. In May 1784, the Vatican removed Newfoundland from the jurisdiction of the Roman Catholic Vicar Apostolic of London, and established it as a separate ecclesiastical see.

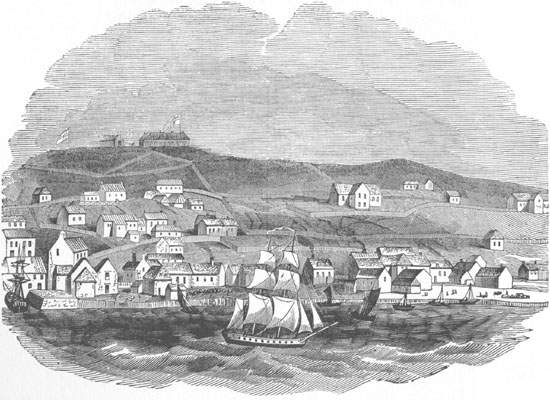

Bishop O'Donel Arrives in St. John's

Upon his arrival in St. John's on 4 July 1784, in company with the priest Patrick Phelan, O'Donel discovered that many in his congregation viewed their situations through the lenses of Irish interests. Several itinerant priests refused to acknowledge his authority and jurisdiction. Some, such as the priest Patrick Power, played on Irish county and provincial factional sympathies in order to seek support from his fellow Leinstermen against O'Donel, a Munsterman.

O'Donel frequently corresponded with Archbishop John Troy of Dublin, who shared his distaste for revolt, disorder, and insubordination. In reply to this O'Donel believed the best course of action would be to regularize the practice of Catholicism. In St. John's he organized his congregation, and erected a chapel, which later writers called the Chapel of St. Louis, in which to celebrate mass and administer the sacraments.

O'Donel's relations with the clergy of other religious denominations were amicable enough, even though they envied his success. He also discovered that Newfoundland Roman Catholicism was subject to the whims and vagaries of British officials' attitudes towards Catholicism. In 1786, Prince William Henry arrived in St. John's and uttered threats against O'Donel and assaulted him, forcing him to hide in an attic for two weeks. In 1790, Governor Mark Milbanke refused permission for one of O'Donel's priests to erect a chapel at Ferryland, and he announced plans to place existing chapels under restrictions, but with the arrival of the more rational judge John Reeves in 1791 the plans for restricting institutional Catholicism were dropped. Under O'Donel, parishes were established at Ferryland, Harbour Grace and Placentia as well as St. John's, and Roman Catholicism began to attract numbers of converts. In September 1796 in Québec City, O'Donel was consecrated as a bishop and as Vicar Apostolic of Newfoundland, and thereafter he maintained a friendly correspondence with Bishop Joseph-Octave Plessis of Quebec. O'Donel's vicariate thus became the first English-speaking diocese in North America, preceding the creation of the diocese at Baltimore by one month.

O'Donel spent much of his tenure in Newfoundland avoiding conflict, muting factional conflict in his Irish congregation, and appeasing British officials on one hand, while encouraging peace, order, and adherence to the British law among his congregations. This was often difficult. In the wake of the French Revolution, rebellion against British rule broke out in Ireland in 1798. The south east, particularly County Wexford, a county of origin for many thousands of Irish in Newfoundland, was embroiled in this uprising. Spurred on by this, two years later, in the spring of 1800, a United Irish rising broke out among Irish soldiers in the garrison at St. John's. Before the insurrection could take hold, the plans were discovered and the rebels brought before British justice. Many years later, in 1863, the historian Charles Pedley alleged that O'Donel had "doubtless derived" his knowledge about the plot "from the confidential communications of the confessional", but no contemporary reliable evidence has even come to light to support this charge that O'Donel violated the seal of the confessional in order to betray his parishioners.

Impact of the Mutiny

The most immediate impact of the mutiny in the St. John's garrison was the subordination of the Irish in general, and Roman Catholicism in particular, prompted by O'Donel's fear of revolution, under the laws of Britain. In 1801, O'Donel's Diocesan Statutes imposed an orthodoxy on the priesthood and lay Catholics which had hitherto been absent. Priests were instructed:

... that public prayers be offered up every Sunday and holiday... for our Most Sovereign King George III, and his Royal Family; to ...strive to turn their flock from the giddiness of modern anarchy, and to inculcate in the people prompt obedience both to the salutary law of England and to the orders of the Governor and magistrate of this island. Finally...we earnestly implore and with all the spiritual authority imparted to us, that all the missionaries place their authority against all plotters, conspirators, and advocates of the Infidel French, and that they sedulously strive to recall such conspirators from the false allurements of the cunning French, whose purpose is to break all the bonds, all the laws by which men are bound together, particularly the English law which may be the most beneficial than all the other laws and statutes of Europe. All this is earnestly desired to be strictly observed.

All the regular clergy of the mission were also to draw up their last wills and testaments to ensure that their property passed to the bishop for the usage of the Church. The message was clear: the practise of Catholicism was to be regularized, priests were to respect the authority of the government and render unto Caesar and accept the authority of the bishop.

O'Donel diligently avoided inciting anti-Catholicism. He made no claim to Catholic educational rights, nor did he demand that Catholics be exempted from swearing oaths on the "Protestant" Bible. In a letter to Bishop Plessis he wrote that such boldness "would increase the bad opinion the adversaries of our faith entertain of us," for "tho' I am not an advocate for ignorance, still I am of opinion it is better in those days of anarchy they should not know how to read than have the manuals of Voltaire, de Lambert, Diderot &c. in their hands."

As a reward for his promotion of social harmony, in 1804 Governor Gower recommended that O'Donel receive an annual pension of £50. While O'Donel's lifelong philosophy was to "render unto Caesar that which is Caesar's," he has sometimes been cast as a "Castle Catholic", a deferential puppet of the British in their quest to use the Church to rule the unruly Irish. Yet in his sensibilities O'Donel was not unique; his Irish contemporary Archbishop John Troy of Dublin, and many other Irish ecclesiastics in this era adhered to the same rubric as the best means available, at that time, for expanding the respect accorded to institutional Roman Catholicism by the British government.

O'Donel also received respect from the local Irish community, of whom more than a few were substantial Protestants like the former military man turned gentleman farmer, Captain William Haly. In 1806, leading Irish Protestants and Roman Catholics founded a non-denominational fraternal society in St. John's, the Benevolent Irish Society (BIS). O'Donel was offered the position of the Society's Patron, which he happily accepted. The BIS had as its motto "He who gives to the poor lends to the Lord", and had as its objective helping the growing numbers of the poor, and providing for families in need and members' families in times of bereavement.

Resignation

Declining health led O'Donel to seek a successor. The Irish Franciscan Patrick Lambert arrived in August 1806, and O'Donel resigned the Newfoundland mission on 1 January 1807. As he left St. John's that July he was fêted by all classes of the population and presented with a silver urn as a token of thanks and affection. He retired to the Franciscan monastery in Waterford, Ireland, where, on 1 April 1811, he died of shock after the chair in which he was reading caught fire.

In an age when the position of the Irish in Newfoundland life was tenuous, and when civil rights did not yet exist, O'Donel served the vital functions of formally establishing Roman Catholicism, a nascent religious and cultural institution, and of becoming a cultural broker, the cushion between the legal requirements of life in a British colony, and Irish social and political aspirations.