Building the Cathedral

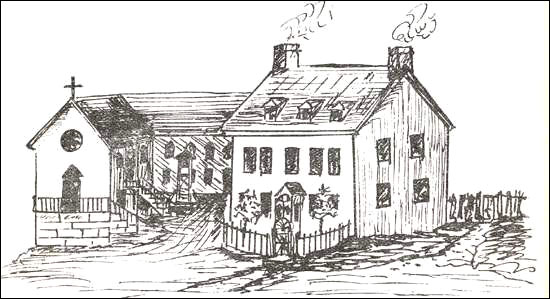

The Roman Catholic Chapel was constructed in 1786 on leased land on what later became Henry Street in St. John's. Built in the style of Irish penal-era chapels, it was a small, unassuming, L-shaped wooden building situated in the back of the town, with a flagpole (instead of an illegal bell) to signal the beginning of religious services. The rapid growth of the Irish population in St. John's during the early years of the 19th century necessitated several expansions to the Chapel, including an extension to the structure and the addition of a gallery.

Fleming's Ideal Cathedral

By the mid-1830s, there were over 10,000 Roman Catholics in St. John's, the Irish Catholic population had a new sense of itself, and the Old Chapel had long outlived its usefulness. Bishop Fleming later described it as "a wretched building little better than an extensive stable, badly built and badly ventilated & now tottering in danger of falling and so wretchedly contracted that a considerable portion of the Congregation are compelled on the Sundays to abide the pelting of the storm, the freezing winds & drifting snows... with their heads bowed in prayer beneath Heaven's own canopy." (National Library of Ireland, P.J. Little Papers, file 140-151, document 141, draft of Fleming "To His Most Gracious Majesty King William the Fourth", undated.)

To replace it, Fleming wished to construct a house of worship capable of holding his congregation, "a temple superior to any other in the Island, at once beautiful and spacious, suitable to the worship of the Most High God, and that may be regarded in after times as a memorial of the piety of the faithful, a pledge of the permanency of our Holy Religion, and an object of holy pride to the fervent Catholics." On an ideological level, Fleming wanted it to be in the classical style, an architectural embodiment of the ideals of Roman ultramontanism. On a political level, the new cathedral was intended to make a statement to the local British ascendancy at Government House that the Irish finally had arrived in Newfoundland and would have to be accommodated.

Petitioning for Land

From 1834 until 1838 Fleming petitioned the British government for a tract of land on the barrens, to the east of Fort Townshend, on the highest ridge overlooking the town of St. John's. This had traditionally been an "Irish" site, favoured for playing games of hurling, and faction-fights. When the nine acres of land was finally granted in May 1838 it was in Fleming's absence, and thousands of inhabitants turned out to fence the land under the direction of Fleming's curate, Fr. Edward Troy. So difficult was the process of acquiring the land that stories came to surround it. In one, Governor Prescott ordered Fleming to take only the quantity of land which could be fenced within half an hour, or alternately, in a day. In another it was said that Queen Victoria herself had granted the land. While there is no documentary or factual basis to these legends, their continued popularity and persistence testifies to the central place in Irish-Newfoundland consciousness which the cathedral occupied, and its central importance in their culture.

Cathedral Construction

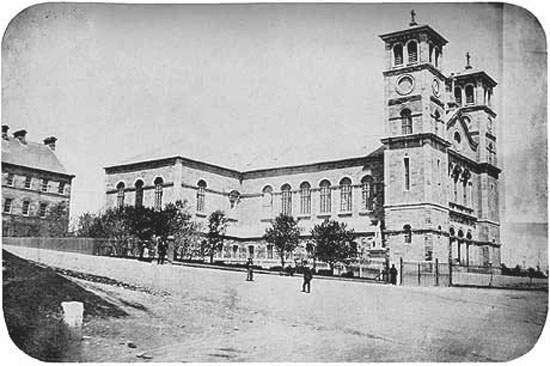

In his letters to governors and other British officials, Fleming wrote in only the most guarded of terms of his desire for land on which to erect "schools, a residence and a parish church". Yet with the land grant, the entire focus of Fleming's episcopacy changed and he preoccupied himself much less with politics and much more with matters related to the construction of the cathedral. Stone had to be procured, along with masons, carpenters, joiners, and labourers. Fleming went to Europe for architectural plans, where he consulted John Jones in Clonmel, Ireland, before settling on a Mr. C. Schmidt, the architect of the Danish Government at Altona-on-the-Elbe, outside Hamburg. Schmidt had taken his architectural education in Rome, and, according to Fleming, his designs reflected ultramontanism. Moreover, Schmidt knew northern Europe's climate well and could design a roof for the St. John's cathedral that would throw heavy loads of snow. With Schmidt's designs, Fleming could "complete a most extensive Cathedral, a House for the Bishop and Clergy, a convent, schools and at an expense far less than by the plans of the English or Irish Architects." Fleming also hired a Waterford builder, Michael McGrath, but after a disagreement replaced him with the builder and stone-carver James Purcell.

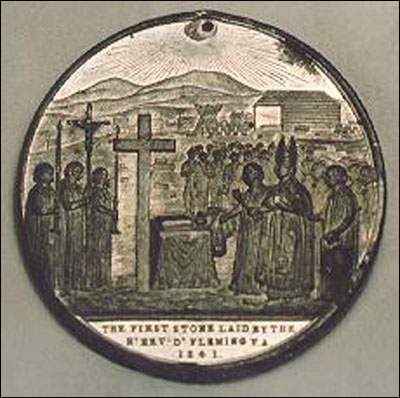

The Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. John's was the largest building project to its date in Newfoundland history. Construction lasted from the excavation of the ground in May 1839, through the laying of the cornerstone in May 1841, until the consecration in September 1855. Contemporary newspapers reported scenes which can only be described as heroic: old women removing soil in their aprons during the two days of excavation which saw 8,800 cubic yards of soil removed; enormous stones blasted out of Signal Hill and hauled across frozen harbour ice by gangs of men and boys, through the town to the site; Fleming up to his waist in water in February on the beach at Kelly's Island in Conception Bay, loading stone onto the small boats of Protestant and Catholic vessel owners for conveyance to St. John's; the largest procession ever through the streets of St. John's in May 1841 for the laying of the cornerstone; and Fleming himself bedaubed with mortar, clambering around the scaffolding 120 feet off the ground, directing the construction personally.

By the 1840s, Fleming had become a driven man, with every minute of his waking hours possessed by the idea of completing the cathedral. From his writings to Rome, it is clear that Fleming believed that the cathedral project was the pivot in the development of Catholicism in Newfoundland, and that there was no small opposition ranged against him and his mission. He believed that the "enemies of our Holy Religion" had been "indefatigably employed" to stop his acquisition of the lands and the building's construction:

...they know well that should I succeed in my efforts to procure this ground and complete the erections upon a site so magnificent it would completely throw the paltry attempts at churches made by the several Evangelical Societies of England in Newfoundland into the shade as to prove in itself an exceedingly strong attraction to their followers, while the circumstance of my successful struggle and so many difficulties and the opposition of interests the most powerful would almost amount to the best proof that the undertaking was dictated by the Almighty.

However, the building of the cathedral had captured the public imagination like no other project in Newfoundland ever had. Fleming's project enjoyed enormous public goodwill, support, and participation by Protestants and Catholics alike. The cathedral also attracted support from Rome, and at Rome's request, the Benevolent Society of Lyon, France, sent funds to help with the project.

By June 1843, construction of the cathedral had created a voracious demand for stone, but substantial progress on the cathedral was visible and labourers were at the peak of their production. Fleming reported to his friend Archbishop Murray in Dublin that "The Cathedral... is the main work that absorbs almost my entire attention - I have at this moment Twenty Six masons at work at 6s/6d. per day. Twelve Carpenters at 6s/o. Four sawyers at 5s. Twenty One Laborers at 3s/3d. and these I am compelled myself to oversee whereby my time is heavily taxed indeed, but I find that it is by far the best means of ensuring a speedy completion of the building and it really is advancing with extraordinary rapidity." As well, he wrote, fishermen with small boats, and "every man that can command a schooner or boat feels proud in contributing his cargo of stone for this stupendous edifice." During the spring of 1843 some 3,000 tons of stone were brought to St. John's harbour, where farmers from around St. John's carted them to the building site, with 80 carts of sand weekly.

Cathedral Completion

By late 1848 the building was substantially complete, and Fleming brought out the Conways, a family of slaters from Waterford, Ireland, to put the roof on the cathedral. With his health failing, Fleming celebrated the first mass in the unfinished cathedral on Old Christmas Day, 6 January 1850, before retiring St. Michael's Convent in Belvedere where he died on 14 July. The Conways subsequently "turned their hand at plastering", and completed the interior walls of the cathedral. Fleming's successor, Bishop John T. Mullock, completed the decoration of the cathedral, and consecrated it in September 1855, with the most famous Irishman in America, Archbishop John Hughes of New York, in attendance.

Irish Influence

Obvious to all at the time of its completion, but virtually forgotten in our present age, is that the St. John's Cathedral was a thoroughly Irish building inside and out, more than any other building constructed by an Irish community anywhere in the New World. The St. John's Cathedral was contemporary with and part of the great boom in church construction which surrounded the age of Catholic emancipation in Ireland. For its day, the St. John's Cathedral was the largest Irish cathedral anywhere outside Ireland, eclipsed in size only by St. Patrick's in New York. The two Irish churches most directly associated with the St. John's Cathedral were St. Teresa's in Clarendon Street, Dublin (the church where O'Connell launched his Catholic Emancipation movement, with its sculpting by Hogan of the Dead Christ) and the Franciscan Friary at Carrickbeg which Fleming and his uncle had built in the 1820s. Reinforcing both the Irish and ultramontane themes, Mullock furnished the St. John's Cathedral with neoclassical and naturalistic statuary by Ireland's most renowned sculptors, John Hogan and John Edward Carew; installed three large prize-winning Irish bells by James Murphy of Dublin; and fitted the cathedral and the adjoining Presentation Convent with a series of stained glass windows by the famed English artist William Warrington depicting Irish subjects.

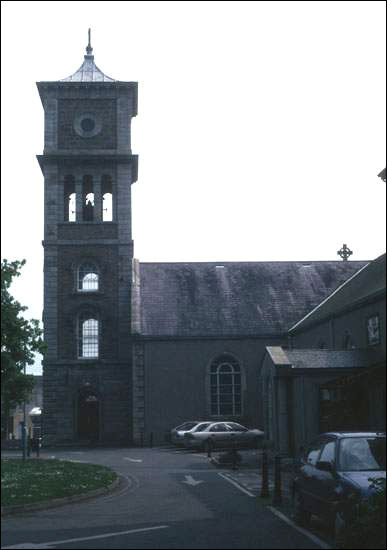

If the St. John's Cathedral came to reflect 'Irishness', it was also a rare example of "trans-Atlantic bounce", in which its own design and material culture, particularly that of its twin towers, in turn influenced the creation of subsequent buildings back in Ireland. Fleming's cathedral and its Romanesque style of design were well-known in their day in Ireland. Subsequently, a number of ecclesiastical buildings in south-east Ireland copied the St. John's Cathedral's style of towers, notably at Thurles Cathedral in Tipperary, in towers in the Vale of Avoca, in the new tower at the Wexford Franciscan Friary, at the Franciscan church in Waterford, and at the Dominican Priory in Cork.

No other Irish building in the New World can boast of such intimate influences from or upon Ireland, and no other Irish building had such an international reputation in its day.