Agricultural Communities

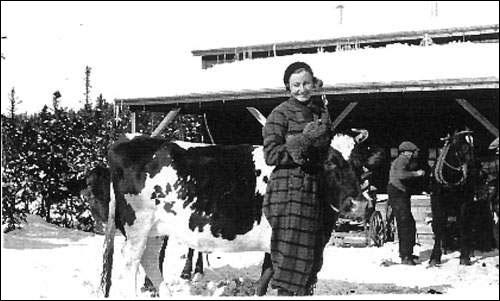

Unlike most of North America, Newfoundland and Labrador have few agricultural communities. The growing season is short, and the soil relatively poor when compared to the other British North American colonies, all of which depended heavily upon agriculture during their early history. Furthermore, Newfoundland settlers quickly realized that they could achieve a higher standard of living by concentrating their labour upon fishing, and importing food from other places. Until 1813 the government officially prohibited fencing in land for farming since it threatened the availability of land for the fishery, but in practice not much was done to discourage the small efforts at agriculture. Many English and Irish settlers came from farming areas, and Newfoundlanders have always grown a few crops near their homes. In the 18th and 19th centuries most households had gardens to supplement families' food, and many had livestock for milk, meat and wool - but people fished for a living and did not sell much farm produce. When families grew more food than they needed, the absence of effective transportation systems made getting surplus crops to market difficult, except in areas close to towns.

Encouraging Agriculture

The early 19th century saw the first attempts by the government to encourage agriculture as a way to replace imports with local produce, and provide for fishing families that might otherwise go on government relief during the periodic depressions in the fishery. The existence in St. John's of an increasingly large market for fresh milk, meat, vegetables and hay, made farming possible along the outskirts of the town. Many politically influential people, such as the Liberal reformer and Speaker of the Assembly William Carson, owned farms themselves and encouraged the government to support agriculture. The government built roads near St. John's, such as Topsail Road, for example, in large part to encourage agriculture. Parts of Conception Bay, and the west coast of the island, which had both good land and a substantial local population, also developed agriculture in the 19th century. Despite the growth in acreage under cultivation, farms were scattered along the margins of fishing harbours and few agricultural "communities" emerged.

Two notable exceptions were Goulds and Kilbride, situated along the road from St. John's to Bay Bulls. In the mid-19th century people began to clear the good agricultural land that was now accessible to St. John's by road. Farmers in this area brought vegetables and milk to St. John's by cart to sell to a merchant or to sell door-to-door. Even here, many families could not make a living though farming alone, and many of these farmers also fished part of the year out of Petty Harbour - Goulds was one of the few places in 19th century Newfoundland not on the coast. As the population grew, residents built a church and school, and started to see themselves as a "community."

Other farming communities were started with aid from the state. The government used bonuses for clearing land and subsidized livestock to encourage the creation of farming communities. In the 1860s farmers settled Eastport, Happy Adventure and Musgravetown. A similar agricultural settlement program in the 1880s led to the establishment of Blaketown, near Conception Bay. The Robert Bond administration at the beginning of the 20th century hoped to establish farming at Whitbourne. While each of these communities put additional acres under cultivation, the distance from markets limited their success. The next great effort to found farming communities had to wait until the economic crisis of the 1930s.

Land Settlement

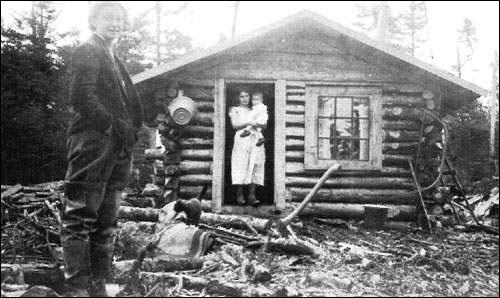

The Great Depression encouraged governments in many countries to try to turn some of the urban unemployed into self-sufficient farmers. Newfoundland was no exception. A voluntary society planned agricultural communities in Newfoundland's interior as a way to employ some of St. John's poor. The Commission of Government, particularly Commissioner for Public Utilities Thomas Lodge, saw much promise in this scheme, and took over the program. Between 1934 and 1942 the Commission of Government's land settlement scheme sponsored the creation of eight farming communities. During the life of the program, about 365 families were relocated from St. John's and depressed fishing communities, to areas that had could potentially be farmed. While the settlers cleared land, and built houses and public buildings such as a school, the government provided provisions, tools and construction material. Lodge hoped that once the first settlement, named Markland, was up and running, its administrators would go on to found other farm communities.

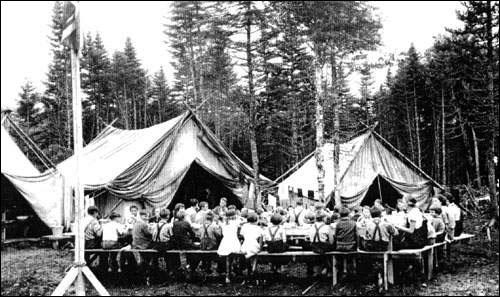

Lodge wanted the program to do more than encourage the urban unemployed and fishing families to grow their own food and thus be self-sufficient, he hoped it would spark a cultural change among Newfoundlanders. The Commission thought Newfoundlanders depended upon the government too much, and wanted to make these people more self-reliant through the "morally-beneficial" work of tending the land. So Markland was a social experiment as much as a farming community. Members of the community worked on communal plots of land and shared the profit. Later, individual farms were developed, but the Commission hoped that the first settlement would provide everyone with a model of civic behaviour. The Commission wanted all Newfoundlanders and Labradorians to work for the good of their whole community, rather than depend upon the government to provide roads, wharves and public facilities.

Community of Markland

Markland was a social experiment in another way as well. The Commission of Government wanted to end the denominational school system in Newfoundland, which it felt led to wasteful duplication of facilities. It failed to change the system in established communities but provided an alternative school in its new model community. Children in Markland were educated in a nondenominational folk school. That school's curriculum included skills such as carpentry and animal husbandry and academic subjects that were selected for the role they might make in remaking Newfoundland's culture such as geography and civics. This model was not followed in other communities, and eventually the school was integrated into the denominational school system.

Markland was expensive for the government, and farmers were slow to produce enough crops to make themselves self-sufficient. Despite weaknesses of the Markland experiment, the Commission opened a series of other farming communities, Haricot, Lourdes, Brown's Arm, Midland, Sanderingham, Winterland and Point au Mal. The land settlement program proved to be an expensive and futile attempt to provide an alternative to the fishery, and many of the settlers drifted back to the fishery or had to continue to be supported by the government. When American military spending gave the settlers opportunities for wage-paying jobs, many of the farmers voted with their feet and took jobs on the bases.

The land settlement program did not live up to the government's unrealistic expectations. The government had to support settlers much longer than intended, and farm output remained low. The authoritarian attitude of administrators and the requirement for settlers to work on communal farms also encouraged dissent among residents. Geographer Gordon Handcock suggests that the individualism among Markland residents, which the land settlement scheme was intended to counter, proved longer lasting than the Commission. He argues the settlers never became a community, but remained little more than a collection of houses. (Handcock 148.) The Commission abandoned the program in 1942, although it established the farming community of Cormack, near the island's west coast, after the second world war to provide employment to returning veterans. Some farming in these communities continued during the rest of the century, but the expensive program achieved neither an economic nor a cultural change in the nature of Newfoundland.

The End of Farming Communities

After Newfoundland's union with Canada the acreage under cultivation declined, and few new areas were opened to farming. Lethbridge, in Bonavista Bay, is one example of an area that came under cultivation after road construction in the area. While there are still many profitable farms and agriculture contributes substantially to the provincial economy, farming "communities" are largely a thing of the past. Land developers found that farmland could be easily subdivided into residential building lots, and sold at a profit. By the end of the 20th century, urban sprawl in the St. John's area took much farm land out of production, and while farms near St. John's still produce crops - they are not really farming communities. Even Goulds, in which the government had protected agricultural land from development, residential housing for people working in St. John's has grown to the point in which farmers are a minority of people in the town.