Royal Air Force

Volunteers from Newfoundland and Labrador died at a higher rate while serving with the Royal Air Force (RAF) than with any other branch of the British Armed Forces during the Second World War. It is perhaps fortunate that the RAF recruited considerably fewer Newfoundlanders and Labradorians than either the Royal Navy or Artillery. Of the 713 who enlisted, some 20 per cent died before hostilities ended.

Service with the RAF, however, was as varied as it was dangerous, and recruits from Newfoundland and Labrador worked all over the world in numerous roles – they patrolled the ocean for enemy vessels, carried out air raids over Axis-held territories, defended Britain from aerial attack, and worked as mechanics, electricians, and other labourers with ground crews. Many also served in a unit the RAF named for their country – the No. 125 (Newfoundland) Squadron.

British Commonwealth Air Training Plan

When war broke out, the RAF desperately needed additional recruits, but lacked the resources with which to train them quickly and properly. Moreover, too few volunteers existed in Britain to meet its demand for pilots, navigators, gunners, and other airmen. As a result, the Air Ministry devised the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (also called the Empire Air Training Scheme) in 1939 to recruit and train airmen from the Dominions. The RAF selected Canada as its principal training ground because it was relatively close to Britain, yet safely distant from hostilities; boasted open and sparsely populated spaces ideal for aerial training; and was able to manufacture frames for trainer aircraft.

The Commission of Government expressed interest in producing volunteers for the program in October 1939, but the Air Ministry was not yet ready to accept recruits as it was still negotiating the plan. In the meantime, it invited the Commission to enlist skilled tradesmen to work with the RAF's ground staff.

Newfoundland and Labrador Governor Sir Humphrey Walwyn issued a proclamation on May 23, 1940 asking for volunteers between the ages of 18 and 35, who stood no less than five feet four inches tall, weighed at least 112 pounds, and were “trained in one of the following trades: fitters, ie., engine and motor mechanics, wireless engineers, wireless mechanics, clock and watchmakers or repairers, electrical instrument makers, electricians, locksmiths.” Such tradesmen, however, were scarce in Newfoundland and Labrador, and recruiting progressed slowly; by mid-June, only 23 volunteers had left St. John's for training in the United Kingdom. Further complicating the RAF's search for ground crew were simultaneous efforts from the Royal Navy and Royal Artillery to enlist volunteers from Newfoundland and Labrador

Recruiting Begins for RAF Air Crew

By early summer, the RAF was prepared to accept volunteers from Newfoundland and Labrador into its Air Training Plan. Walwyn issued a second proclamation on June 22, this time calling for men between the ages of 18 and 28 to serve as pilots, or between the ages of 18 and 32 to serve as wireless operators/air gunners. A committee of officers from the RAF and the Royal Canadian Air Force visited St. John's in August to screen applicants; before the month was over, a first draft of 52 recruits – four pilots, four navigators, and 44 wireless air gunners – travelled to Toronto for training. Half of these men died before the war ended.

Once in Canada, recruits trained in a flight simulator, studied navigation, and received instruction in marching and other military practices. In October, the RAF assigned them to one of the many Elementary Flying Training Schools scattered across Canada, where they eventually made their first solo flights before moving on to an Intermediate Flying Training School. After some 100 hours of flying and 10 months of training, successful recruits received their wings and proceeded to the United Kingdom.

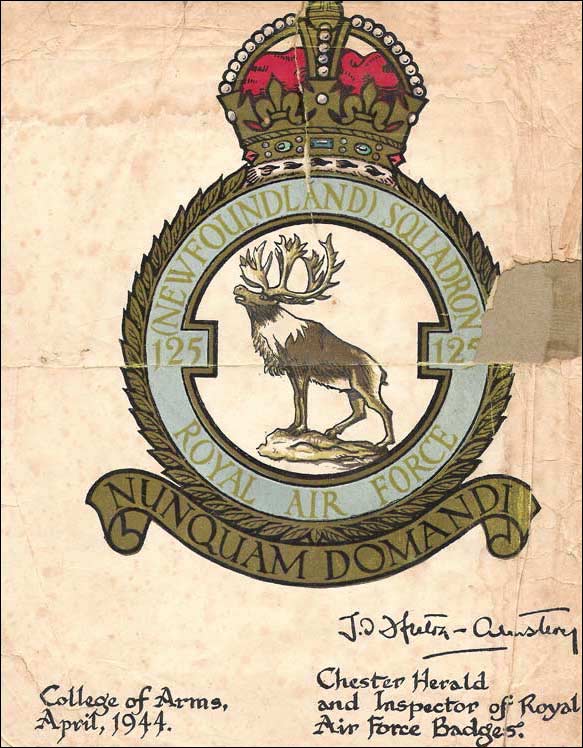

No. 125 (Newfoundland) Squadron

Recruiting efforts in Newfoundland and Labrador, meanwhile, had grown increasingly difficult, and about half of all applicants failed to meet the RAF's medical requirements. To remedy the situation, the Commission of Government donated $500,000 to the RAF in early 1941 to help establish the No. 125 (Newfoundland) Squadron. Alongside contributing to the British war effort, the Commission hoped the creation of a Newfoundland squadron would prompt more Newfoundlanders and Labradorians to volunteer for the RAF. It was here that many of the first 52 recruits served.

Although the Commission had intended the squadron to be solely composed of air and ground crew from Newfoundland and Labrador, the country did not produce enough experienced personnel to form a unit. Instead, the RAF supplemented the squad's membership with pilots who had previously fought in the Battle of Britain and airmen from other Dominions. Throughout the war, recruits from Newfoundland and Labrador formed only a minority of the unit's personnel.

The Newfoundland squadron served as a night fighter unit, patrolling for enemy aircraft and naval vessels from 10 p.m. until sometime after midnight. Pilots initially flew the Defiant Mark I, a two-seater fighter plane which carried a gunner in the rear, but later converted to radar-equipped Beaufighters and Mosquitos. The cockpit of each Beaufighter displayed the name of a different Newfoundland city or community – St. John's, Corner Brook, Deer Lake, Buchans, Harbour Grace, Grand Falls, Bell Island, Bonavista, St. George's, Heart's Content, Grand Bank, and Botwood.

Before the war ended, the squadron destroyed some 44 enemy aircraft, and damaged 20. Although airmen from other countries accounted for the majority of these attacks, volunteers from Newfoundland and Labrador also played their part. On the night of July 28, 1944, Flight Sergeant Royal Cooper of Trinity Bay and his navigator, Flight Sergeant Patrick O'Malley of Edinburgh, shot down the unit's first V-1 flying bomb – a new form of guided missile German forces had been using with much success.

On April 26, 1942, Flight Officer Randal George White of St. John's attacked a German aircraft and earned the squad a claim of “probable destroyed.” White later became the highest-ranking Newfoundlander in the RAF when officials promoted him to Squadron Leader on February 11, 1945.

Other Roles

Aside from the No. 125 (Newfoundland) Squadron, volunteers from Newfoundland and Labrador served in a variety of RAF units, and performed a wide range of tasks in every theatre of war. For example, Leading Aircraftsman Hubert French of Bell Island served as a gunner in India and Myanmar (then Burma), while Flight Officer Walter Vatcher was part of a fighter squadron that raided Dieppe in August 1942.

The most decorated airman from Newfoundland and Labrador was navigator Allan Ogilvie of Grand Falls, who won the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) after completing his 50th combat mission. However, while returning from his 51st mission on March 11, 1943, an enemy fighter shot down Ogilvie's aircraft and forced him to parachute into German-occupied Northern France. With help from the French Resistance, Ogilvie completed a treacherous three-month journey back to England, where the RAF awarded him the Bar to the DFC for his courage and heroism.

War's End

After the war in Europe ended in May 1945, the RAF continued to send recruits to the Pacific theatre until hostilities against Japan ceased in August. The No. 125 (Newfoundland) Squadron remained in England and spent much of the summer practice flying a new model of Mosquito aircraft over the United Kingdom and occupied Germany. The unit disbanded on November 20, 1945, and by the end of the year, most RAF recruits from Newfoundland and Labrador had returned home. However, fatalities were high, and between 1940 and 1945, some 135 of the country's airmen and ground staff had died on duty.