The Moores Government 1972-1979

The election of a Progressive Conservative government led by Frank Moores in 1972 marked a turning point in Newfoundland and Labrador politics. Seeking to distance itself from Joseph Smallwood's domineering leadership style, resettlement plans, and industrialization policies, the new administration promised to make government more democratic and accountable, promote rural development, and take greater control of the province's natural resources.

Although it succeeded in bringing more transparency to government proceedings and in distributing power more evenly among elected officials, the Moores administration did little to change the province's overall economic strategy. It continued to sink large sums of public money into large-scale industrial developments while providing comparatively little support to fisheries and rural development. Socioeconomic problems worsened in the 1970s, as unemployment and the public debt increased.

Political Reforms

The Moores Conservatives introduced a number of political reforms aimed at making government more transparent and accountable, thus distancing the new administration from Smallwood's self-described “democratic dictatorship.” First among these was a Conflict of Interest Act, passed in 1973. Newfoundland was the first province in Canada to pass such legislation. The act required elected officials and senior civil servants to make pubic any investments or relationships that could influence the performance of their official duties. It also forbade MHAs from voting or speaking on issues where such a conflict existed.

The government introduced a daily oral question period to the House of Assembly, a feature already commonplace in most other legislative assemblies across the country. Question period increased government accountability by giving opposition parties an opportunity to ask the premier and cabinet to explain their policies and decisions in a public setting.

Power, which had been concentrated in the premier's office under Smallwood, became more evenly distributed among members of the cabinet. Ministers acquired greater independence and more control over their departments than in the past, and a planning and priorities committee of senior ministers was established to discuss and create policy on resource development, government services, and social programs. In 1975, the government created an independent and non-partisan provincial ombudsman to investigate complaints from citizens who felt they were unfairly treated by government departments or agencies.

Moores's leadership style altered the tone of provincial politics. John Crosbie, a cabinet minister under Moores, wrote in his autobiography that “Frank Moores was a complete contrast to Joey Smallwood. … Discussion and debate were encouraged in cabinet. Frank was an engaging, friendly, effusive personality who was more than happy to delegate authority to others.” According to journalist Rex Murphy, “Moores took the premiership as a job, whereas Smallwood held it as some sort of covenant with Newfoundland destiny.”

Industrialization Projects

While bringing about political reform, the Moores administration had little positive impact on the economy. Much of its time and resources were monopolized by Smallwood's unfinished – and ultimately unsuccessful – industrial projects instead of being redirected towards the rejuvenation of the fisheries and rural development.

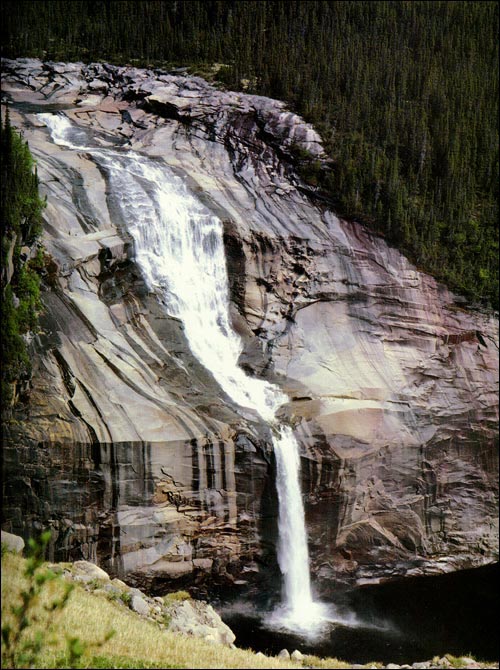

The government spent a great deal of time trying to renegotiate the sale of Churchill Falls electricity to Hydro-Québec, without any success. Hoping to develop power on the Lower Churchill River, it paid the British Newfoundland Corporation (BRINCO) $160 million in 1974 to buy back its Labrador water rights and obtain a controlling interest in the Churchill Falls (Labrador) Corporation. Subsequent efforts to secure a transmission route across Québec into lucrative North American markets failed and the Lower Churchill remained undeveloped.

Smallwood's linerboard mill at Stephenville was another drain on government money and resources. By the time Moores took office in 1972, the mill's projected cost had increased from $75 million to $122 million, and government guarantees had more than doubled from $53 million to $110 million. By 1976, the mill was losing $100 on every ton of linerboard it produced and needed government subsidies to stay afloat. The province closed the mill, owned by the Crown corporation Labrador Linerboard Limited, in August 1977 and the following year sold it to Abitibi-Price Ltd. for $43.5 million.

A third troubled megaproject was the Come By Chance oil refinery, owned by American industrialist John Shaheen. Like the linerboard mill, it received millions of dollars in government loans, including $60 million from the Conservatives in 1975. The refinery opened in 1973, began losing money immediately, and declared bankruptcy three years later, putting 500 men and women out of work. The project was $42 million in debt to the province when it became insolvent.

Rural Development

While large industrial projects dominated the government's attention and budget, other areas of the economy remained neglected. The Conservatives failed to follow through on promises to support rural areas, directing only between five and 10 per cent of government spending on fisheries, agriculture, forestry, tourism, and rural development. Although the Moores government denounced Smallwood's resettlement plans, it did little to prevent continued outmigration from rural to urban areas.

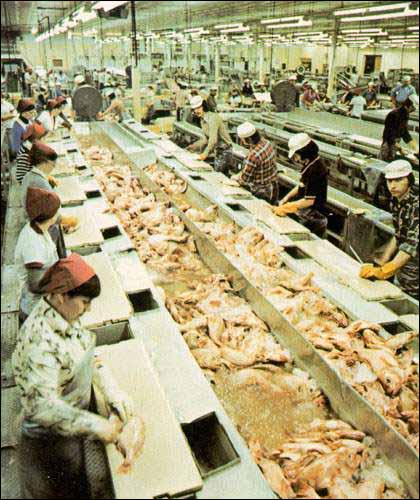

The fisheries remained generally troubled for much of the 1970s, due in large part to overexploitation. In an effort to protect depleted stocks, the federal government extended its jurisdiction from 12 to 200 miles beyond its coastline in 1977, a decision the province strongly encouraged. Despite this important step forward, Ottawa failed to properly regulate the number of fishers working in its waters, while the province allowed too many processing plants to operate. Overcapacity resulted in glutted markets, low incomes, and continued depletion of the stocks.

Unemployment was a constant problem during the Moores years, exacerbated by a climbing birthrate from the late 1940s. In 1970, the government estimated it would have to create between 3,000 and 4,000 new jobs annually to accommodate the expanding labour force. During its first five years in power, the Moores administration increased the number of civil servants from 7,600 to 9,300. By 1977, the province was spending more money on salaries than it received in tax revenues. At the same time, the unemployment rate had reached 34 per cent (approximately 82,000 people). To pay for salaries, industrial projects, and other costs, the province relied on loans and federal transfer payments; by the time Moores left office in 1979, the provincial debt was approximately $2.6 billion, up from $970 million in 1972.

A 1977 People's Commission on Unemployment blamed the province's socioeconomic problems on underdevelopment and the mismanagement of its resources by the federal and provincial governments. “Our natural and human resources have become the fuel for someone else's development,” it stated. “Our hydro power enhances the position of Hydro Quebec on New York bond markets, while we suffer the indignity of the lowest credit rating in Canada. Our iron ore creates manufacturing jobs in Southern Ontario while we pay the highest prices in Canada for the automobiles it helps to build. Our fish goes in blocks to markets in the United States, creating jobs there in processing and packaging. The tax dollars spent on the educational and technical skills of our people end up as an investment in the economy of Ontario or Alberta, as our workers are forced to emigrate because there are no jobs at home.”

Oil-Fuelled Optimism

A potential bright spot on the province's economic outlook was offshore oil. Throughout the 1970s, much exploratory drilling took place on the continental shelf. Although the province was engaged in ownership disputes with Ottawa over offshore petroleum resources (which remained unresolved while Moores was in office) there was much local optimism that a significant find would create jobs and boost provincial revenues. In 1979, Chevron Standard Limited discovered the Grand Banks' first commercial oilfield, known as Hibernia.

A new federal government in June of that year signaled another step forward for the local oil industry. Conservative leader Joe Clark was much more inclined to recognize Newfoundland and Labrador's ownership of offshore resources than outgoing Liberal Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. The negotiations, though, were continued by another provincial administration. In January 1979, Moores announced that he would retire as premier and leader of the Progressive Conservatives. Brian Peckford replaced him in March and remained in office for the next 10 years.