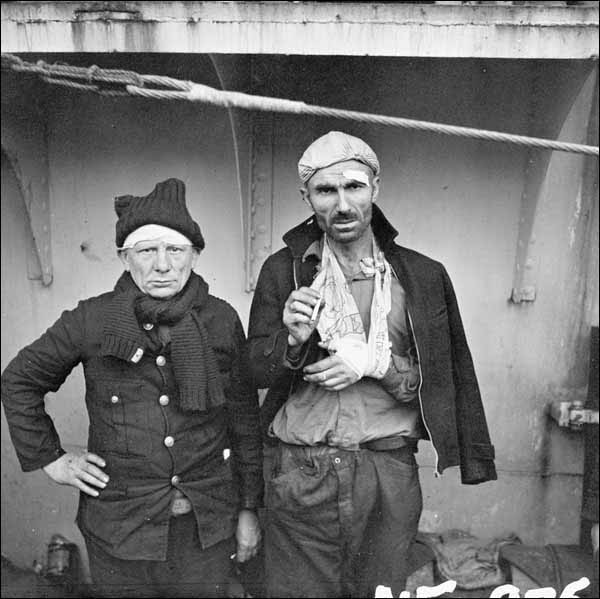

Merchant Mariners

"The Battle of the Atlantic was not won by any navy or air force, it was won by the courage, fortitude and determination of the British and Allied merchant navy."

Rear Admiral Leonard Murray

Commander-in-Chief Canadian North Atlantic

Merchant mariners played a vital role in the Second World War, transporting desperately needed food, equipment, and personnel to Britain and other Allied countries on non-military vessels. Although not part of the armed forces, these men and women faced constant threat from enemy submarines, destroyers, and aircraft seeking to cut off supply lines. Thousands of merchant mariners were killed at sea; hundreds more were captured and sent to prisoner of war camps.

Despite these risks, recruitment was high in Newfoundland and Labrador, where some 10,000 volunteers joined the service before hostilities ended. Many served on Newfoundland ships, such as the passenger ferry Caribou, while others joined the merchant navies of different Allied countries, including Canada, the United States and Panama. Most, however, served on British ships.

Early Recruitment

Britain relied on imports from North America for its war effort. Any significant interruption of the shipping lanes across the North Atlantic would have made likely a British defeat at German hands. Recognizing the importance of a strong merchant navy, the British government sought volunteers from Newfoundland and Labrador soon after hostilities broke out.

The response was enthusiastic. Alongside the hundreds of sailors already serving on commercial vessels, thousands more volunteered after the call went out. Most were older men or teenaged boys not eligible to serve in the armed forces. Small numbers of women also joined, generally as stewardesses on passenger ships. Upon acceptance, recruits usually signed on for a certain number of voyages with the possibility of renewal. However, if a volunteer decided to stay ashore, he or she had the right to do so. Although some mariners attended a gunnery school on the Southside of St. John's, most received little or no safety or emergency training – many did not even know how to properly use a life jacket.

Nonetheless, merchant mariners were prominent on the front lines and suffered heavy casualties. The largest threat came from German U-boats, which patrolled shipping lanes in groups and torpedoed passing merchant vessels. At the peak of hostilities, between late 1942 and early 1943, U-boats sank on average 33 Allied merchant ships each week. Most losses occurred in the North Atlantic, but Axis forces sunk many merchant ships off the coasts of South America and Africa. Unable to replace destroyed shipping vessels quickly enough, Britain pressed every available ship into service, some of which were quite old. This presented another danger for merchant mariners, who now had to serve on vessels previously deemed unseaworthy.

Convoys

To counter the threat of U-boat attacks, merchant vessels crossed the Atlantic in convoys – groups of ships arranged in columns and escorted by military vessels. Aircraft provided support as well, but had limited range in the early stages of the war and could only accompany convoys part way into the Atlantic before having to turn around. Allied forces eventually solved this problem by installing flight decks on some merchant ships.

Despite the advantage of travelling in convoy, the system still had problems. Foggy weather and blackout conditions resulted in frequent collisions in the crowded convoy lanes. There were not enough navy ships or aircraft to accompany every convoy, and even with an escort, losses from enemy mines, U-boats, surface boats, and aircraft were high. The Allies lost some 5,150 merchant ships during the war.

Oil tankers were a favourite target of enemy submarines because they provided the fuel for Allied factories, tanks, automobiles, and airplanes. Boatswain Edmund Wagg of Burin was aboard one such vessel, the unarmed T.C. McCobb, when an Italian submarine attacked and sank it in the South Atlantic on March 31, 1942. After abandoning ship, Wagg managed to find a lifeboat and began rowing toward the Brazilian coast. He rescued 18 of his shipmates from the water before being taken aboard a passing Allied ship. After the war, Wagg received a commendation from the United States government for his heroism.

Although many Allied ships were lost making the Atlantic crossing, some went down closer to shore. The Caribou passenger vessel, which ran from Port aux Basques to Sydney, Nova Scotia, was sunk by a German torpedo just 64 kilometres off the coast of Newfoundland on October 14, 1942. Of the 46 merchant mariners serving on board, most of whom were Newfoundlanders, only 15 survived. Also killed were 49 civilian passengers and 57 military personnel.

Many ships attacked in the North Atlantic found refuge in the port of St. John's, where dock employees serviced some 10,000 Allied vessels over the course of the war. Mariners from these torpedoed ships lived in St. John's until they could return to their home ports or ship out once again on other vessels.

In an effort to boost morale, a group of St. John's citizens and businessmen connected with local shipping companies in 1942 to establish a club for visiting merchant seamen. Located in the old Mechanics Hall (near the site of the present-day War Memorial in downtown St. John's), the club provided various forms of entertainment for mariners, including dances, movies, billiards, table-tennis, and cooked meals.

War's End

Before the war ended, it is estimated that some 60,000 Allied merchant mariners died in service – 333 of whom were from Newfoundland and Labrador. Determining the exact number of fatalities, however, is problematic. Unlike the armed forces, the merchant navy did not maintain consistent records of its recruits and casualties. This is largely due to the nature of the service – most merchant mariners served on privately owned vessels commandeered by the state and sent to war in the national interest. No method existed for formally recording their numbers and many of the companies that owned the ships disappeared in the decades following the war.

Despite the important and dangerous role merchant mariners played during the war, they received little recognition once hostilities ended. The Commission of Government, and later the Canadian government, failed to recognize merchant mariners as veterans, excluded them from war benefits and barred them from rehabilitation programs designed to help members of the armed forces readjust to civilian life.

Gradually, however, the merchant navy's contribution to the war effort was acknowledged. In 1999, Ottawa declared Canadian merchant mariners – including Newfoundlanders – full-fledged veterans; in 2000, then federal Veterans Affairs Minister George Baker made merchant mariners eligible to receive benefits and pensions; in 2003, Canada formally recognized September 3 as Merchant Navy Veterans Day.

Today, a memorial stands at the Marine Institute in St. John's to honour merchant mariners. Installed in 1997 by the Newfoundland chapter of the Canadian Merchant Navy, the monument bears the names of 332 seamen and one woman from Newfoundland and Labrador killed by enemy action during the Second World War.