Government Response to the Great Depression

The outbreak of the Great Depression in the fall of 1929 caused much economic hardship in Newfoundland and Labrador. Most damaging was a breakdown in world trade, which caused the country's revenue to plummet. Despite its shrinking income, the government still had to make interest payments on a sizeable national debt and provide essential services to the public. Widespread unemployment during the 1930s exacerbated an already difficult situation by forcing the government to spend millions of dollars on various relief programs. Most, however, were ineffective. Dole rations, for example, were heavily policed and much too small to live on; land settlement also ended in failure.

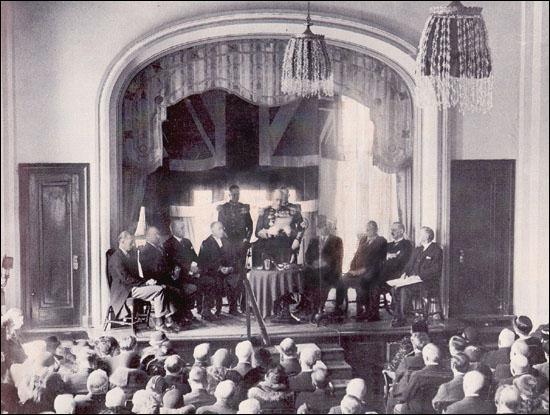

At the same time the government increased relief spending, it also contributed to the crisis by laying off employees and making cuts to health care, education, and other social programs. When allegations of corruption surfaced against high-ranking political officials in 1932, it intensified the public’s mounting dissatisfaction with party politics and led to the swearing in of the Commission of Government in 1934. For the most part, however, the new regime proved equally incapable of improving the Depression’s impacts on the working class and on the country as a whole. It was not until the employment boom of the Second World War that the country recovered.

Financial Crisis

The impact of the great Depression was devastating to Newfoundland and Labrador’s export-based economy. A sudden slump in international trade dramatically reduced revenue from fish, mineral, and pulp and paper exports. Profits decreased from $40 million in 1930 to only $23.2 million in 1933. The national debt, meanwhile, continued to climb. By the end of 1933, the government owed $100 million – mostly to the United Kingdom and the United States. Interest payments alone accounted for 63.2 per cent of the country’s shrinking income.

The government responded to the crisis by borrowing more money from abroad. As the Depression deepened, however, the pool of willing lenders dried up. Britain and Canada worried that it would reflect badly on the Empire if Newfoundland and Labrador failed to meet its interest payments and agreed to lend the government money in return for a number of concessions. One was the appointment of a financial advisor to help organize the country’s finances. Sir Percy Thompson, deputy chairman of the Board of Inland Revenue, filled this position in August 1931. At around the same time, the Newfoundland and Labrador government appointed Montreal businessman Robert J. Magor to investigate various government departments and reduce spending wherever possible.

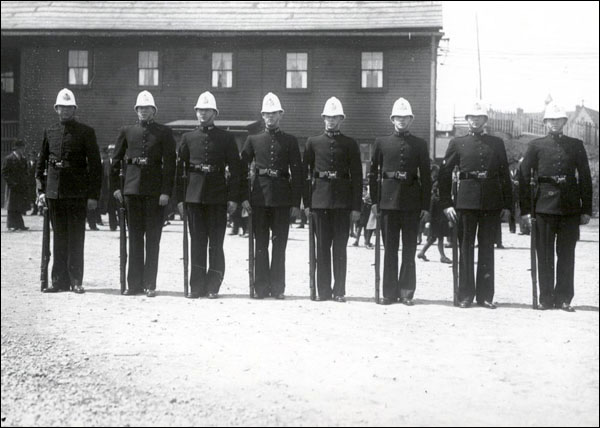

Unfortunately, it was the country’s poor and vulnerable who were most negatively affected by the ensuing government cutbacks. The government laid off one-third of its civil servants and reduced wages for the rest. At the same time, it introduced new taxes that increased the cost of living by approximately 30 per cent. The government also slashed spending on health and education, but doubled its police force in 1932 to better maintain law and order amid a growing atmosphere of public unrest. Perhaps most frustrating to the country’s unemployed, however, were Magor’s efforts to reduce public relief payments, widely known as the dole.

Government Relief

The dole was a small amount of support the government distributed to the poor and unemployed. A typical ration included flour, pork, split peas, corn meal, molasses, and cocoa. It provided for only about half of a person’s nutritional needs. The government did not give more partly because it had very little money to spare during the Depression; by 1933 it was already spending more than $1 million on relief payments annually.

Government officials were also afraid that if they gave too much, people would become comfortable on the dole and stop trying to find work elsewhere. A third concern was that dole payments should not exceed the income of the country’s working – yet impoverished – fishers. “The tragedy of Newfoundland,” Commissioner Thomas Lodge wrote in 1939, “is not that the scale of able-bodied relief is so low. It is that the scale differs so little from the standard of living enjoyed by the workers who manage to retain complete independence.”

Some government officials worried that relief expenditures were becoming too large a drain on the country’s finances. To keep costs down, they closely policed dole applicants to ensure that only those who desperately needed relief received it. The government also hired a limited number of relieving officers, which made it difficult for a lot of people to apply for the dole. The officers had sweeping powers to investigate applicants and to determine how much government support they should obtain.

This contributed to the economic and social hardships experienced by the poor and working class during the Depression. If people supplemented inadequate dole rations by hunting or farming, then they risked being cut off from government support. Furthermore, Magor recommended that the government not only refuse relief to people who cheated the system, but also to those who knew of abusers and did not report them. This helped create an atmosphere of paranoia, discontent, and oppression in Newfoundland and Labrador during the 1930s.

The Commission of Government

The Commission of Government only marginally improved matters when it came into power in 1934. It distributed free milk and cod liver oil to children, raised the health department’s budget, and slightly increased dole orders. Destitution remained widespread and the relief system was still harshly policed, left people hungry and malnourished, and did not allow recipients to buy their own provisions. The replacement of white flour with brown was a particularly sore point, as many applicants felt the new flour was difficult to bake with.

The Commission also introduced a land settlement program to Newfoundland and Labrador which had a promising start, but eventually ended in failure. Under this program, the government helped families establish farms, raise animals, and build communities in various uninhabited parts of the country. The intention was for people to eventually support themselves off of the land and pay back the government’s investment. The first and largest program took place in May 1934 at Markland. Others followed in such places as Brown's Arm, Lourdes, and Midland.

The settlements, however, were run by trustees and not by the people who lived there. This made the settlers feel as though they had no control over their lives. In 1936, for example, the government evicted one family from Markland for refusing to send their children to the local school; seven men objected to the expulsion and were also forced to leave. By 1937, the government felt the land settlement families would not be able to pay back the money it had invested in them and began to scale back the program. It dismantled the program in 1941.

By then, however, the Second World War had brought widespread prosperity to Newfoundland and Labrador. The country reported a financial surplus for the first time in years and unemployment had virtually disappeared. When hostilities ended, it was time to replace the Commission with a new form of government. Canada’s social security net made Confederation an attractive option for many voters who still remembered the hardships of the 1930s.