Disasters 1892-1929

Some of Newfoundland and Labrador's best-known and most destructive disasters occurred during the era of Responsible Government. The Great Fire of 1892, for example, burned down most of St. John's in just 12 hours and left 11,000 people homeless. During the 1914 seal hunt, 251 men drowned or froze to death in what became known as the Newfoundland and Southern Cross disasters. In 1918, a particularly virulent strain of influenza killed more than 600 people across the country and wiped out the Inuit community of Okak. Finally, a tsunami struck the Burin Peninsula in 1929, where it killed 28 people and left thousands more homeless.

While some of these disasters arose from environmental events, such as the tsunami, others were triggered by human error or negligence and often resulted in legislative changes. This was the case with the Great Fire and the 1914 sealing disasters, which prompted government officials to restructure the St. John's fire departments and revise the regulation of the seal hunt. Regardless of their origin, however, each disaster inflicted tremendous social and economic cost to Newfoundland and Labrador. Although most communities were eventually able to adapt and rebuild, some, such as Okak, disappeared entirely.

Great Fire of 1892

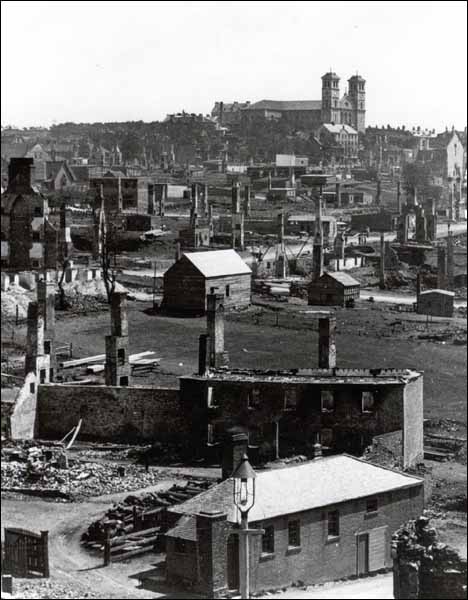

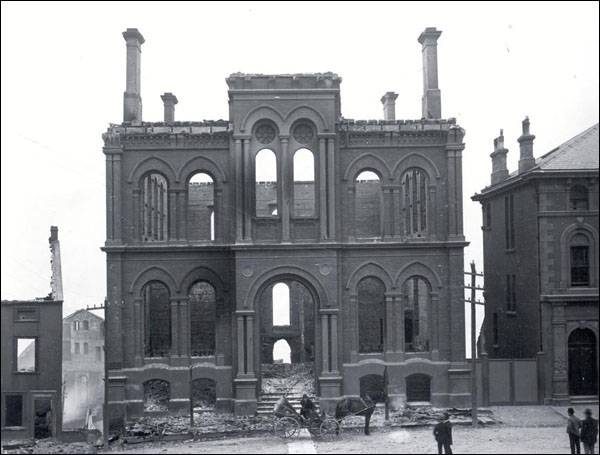

At about five o'clock on 8 July 1892, a small fire broke out in a St. John's stable near the corner of Freshwater and Pennywell Roads. Although firefighters arrived on the scene 30 minutes later, a water shortage prevented them from extinguishing the flames. Earlier that day, the city had turned off its water supply to let workers lay down new pipes; as a result, all hydrants in the area were dry. A nearby water tank was equally useless because firefighters had forgotten to refill it after a recent training exercise.

Hot dry weather conditions and strong winds further facilitated the fire's spread. The city's many wooden houses and shingled roofs were as dry as tinder following a month of high temperatures and no rain. A powerful wind was also blowing on July 8, which helped fan the fire and carry burning debris from one parched rooftop to another. By eight o'clock the fire had reached the city's downtown, where it continued to burn until 5:30 the following morning. When the sun rose on July 9, more than two-thirds of the city lay in ruins and 11,000 people were homeless.

Immediately following the fire, government officials ordered workers to build temporary housing at Bannerman Park, the Railway Depot, and other suitable spaces. A Fire Relief Committee helped distribute food, clothing, and other provisions among fire victims; its members also helped find employment for those left jobless by the fire.

The disaster also prompted the government to restructure the city's fire departments. Officials passed legislation in 1895 which created a mixed police and fire force, and transferred control of the fire department from the St. John's Municipal Council to the Constabulary's Inspector-General.

1914 Sealing Disasters

Two separate yet simultaneous tragedies occurred during the 1914 seal fishery which later prompted the Newfoundland and Labrador government to change the way it regulated the hunt. In late March or early April, the sealing vessel SS Southern Cross sank while returning from the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The ship's captain and 172 crewmen died in the shipwreck, making it the most fatal disaster in Newfoundland and Labrador's sealing history.

However, a second sealing disaster was also unfolding to the north which claimed an additional 78 lives. Between March 31 and April 2, 132 sealers with the SS Newfoundland spent 53 consecutive hours stranded on the North Atlantic ice floes in blizzard conditions. More than two-thirds of the men died before rescuers could find them, and many of the survivors lost one or more limbs to frostbite.

Photographs and stories of the dead and injured men circulated throughout the country and greatly affected public attitudes surrounding the seal fishery. In 1914, the government established a commission of enquiry to investigate the two disasters. Although the commissioners laid no criminal charges, their findings made it clear that sealers faced unnecessarily dangerous working conditions while on the ice and at sea. The enquiry's recommendations prompted government officials to introduce new legislation in 1916 holding ship owners and captains more accountable for their crewmembers' safety.

Spanish Influenza

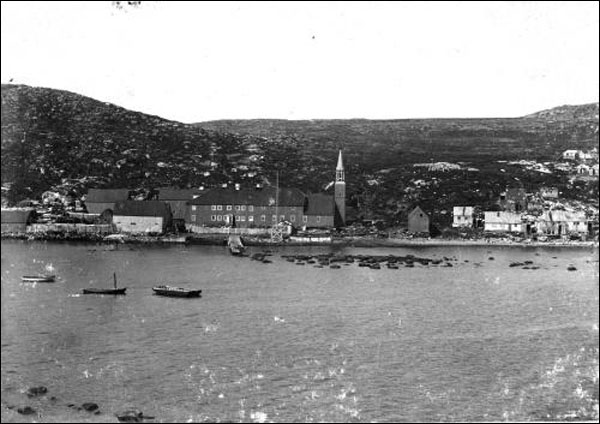

The Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918-19 killed at least 20 million people around the world, and more than 600 people in Newfoundland and Labrador. The disease was especially destructive in Labrador, where few medical resources existed to curb its spread. Within weeks of its outbreak, the virus killed close to one third of Labrador's Inuit population and entirely wiped out the northern Inuit village of Okak.

Although the Spanish influenza did not originate in Newfoundland and Labrador, the country's many ports made it vulnerable to infection. The disease first reached St. John's on 30 September 1918 when a steamer carrying three infected crewmen arrived at the city's harbour. A doctor diagnosed the first two local cases of influenza on October 5 and sent both people to a hospital. Within weeks, the virus had spread across the island, killing 232 people and infecting many more.

By early November, the coastal steamers SS Sagona and SS Harmony had departed St. John's harbour for various Labrador ports. Despite the highly contagious nature of the influenza virus and its prevalence at St. John's, government officials placed few restrictions on shipping arriving at or departing from the city's port. By the time the Sagona and Harmony arrived at Labrador, each ship was carrying infected crewmen or passengers. The disease quickly spread throughout Labrador's coastal communities, where it killed hundreds of people in a matter of weeks.

Burin Tsunami

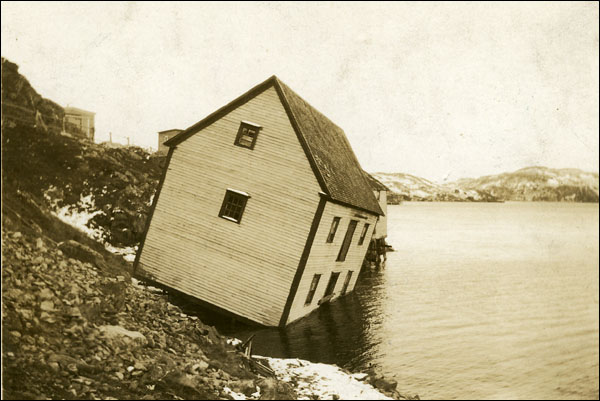

At about 5:00 on the afternoon of 18 November 1929, an earthquake occurred on the Grand Banks which measured 7.2 on the Richter scale and sent a tsunami racing towards Newfoundland's Burin Peninsula. The area's residents had noticed ground tremors, but no seismographs or tide gauges existed on the island to warn of the approaching danger.

At about 7:30 p.m., giant waves measuring between three and 27 feet tall hit the coast at 40 km/hr. Their force crushed buildings, lifted houses off their foundations, swept schooners and other vessels out to sea, and destroyed wharves, flakes, and other structures along the peninsula's coast. The disaster killed 28 people and left hundreds more homeless, making it the most destructive earthquake-related event in Canadian history.

Unfortunately, the Burin Peninsula had no way of requesting help from the outside world because a recent storm had knocked out its main telegraph wire. It was not until November 21 that news of the disaster reached the rest of the island after the SS Portia made a scheduled stop at Burin and radioed St. John's for assistance. The Newfoundland and Labrador government immediately dispatched a relief vessel to the Burin Peninsula with a shipment of medical supplies, food, blankets, and other provisions. Public donations also poured in from across the country and within weeks had amounted to $250,000. Despite these relief efforts, the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 prevented many communities from fully recovering until the 1940s.