The Military Aspects of the Wars

The Napoleonic wars did not cause much direct damage to the island. The turmoil of the French Revolution, which began in 1789, left France in no position to carry on organized warfare overseas. Its navy lost many experienced officers to the guillotine, its dockyards were ruined, and the blockade of France by the British navy after 1793 made it extremely difficult to restore the French navy to fighting form.

The British recognized that the greatest threat to Newfoundland and the other British North American colonies came from privateers, and moved quickly to capture the French islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon so they could not be used as a privateering base. An expedition from Halifax removed the residents, installed a British garrison, and placed the islands under the jurisdiction of the Newfoundland governor. Though the islands were restored to France under the terms of the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, the next phase of the war resumed before any of the inhabitants could return. France did not regain possession of the islands until 1816.

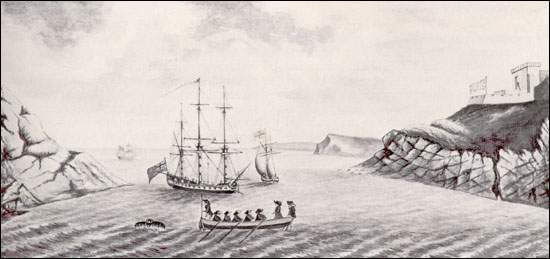

Despite the effectiveness of the Royal Navy and the blockade, the British knew from experience that a French expedition could slip into the North Atlantic and threaten the fisheries. For this reason, the outbreak of war saw a flurry of activity in Newfoundland to improve local defences. The number of warships stationed there increased, and so did the garrison at St. John's. Under the direction of Major Thomas Skinner, the chief military engineer, considerable effort went into improving the fortifications and harbour defences there, including for the first time substantial works on Signal Hill overlooking the Narrows and the harbour. Not everyone agreed that this was a wise use of money, but the investment seemed justified when a French squadron under Admiral de Richery threatened St. John's in 1796.

As had been feared, de Richery managed to slip out of Cadiz into the Atlantic. His plan was to join another squadron from Brest and descend on Newfoundland to disrupt the fishery and destroy St. John's. The timing was good, since the British warships stationed in Newfoundland were under strength, not to mention old and weak, the garrison numbered less than 600 men, and many of the new defences were still in the planning stage. Governor Wallace made a brave show of strength. This is often credited with causing the French to withdraw, but de Richery's discretion was probably motivated by the failure of the Brest squadron to join him. De Richery still managed to destroy Petty Harbour and Bay Bulls, disrupt the bank fishery, and cause a considerable amount of damage to the British fishery at Labrador.

The attack reinforced support for plans to improve defences in St. John's, and even Placentia, which had been sinking into military obscurity, was given a modest increase in the size of its garrison. But de Richery's raid proved to be the last serious threat of the war. When enemy ships failed to appear on the coasts, and the fisheries remained undisturbed, the batteries at St. John's fell into neglect and the outharbours were left virtually defenceless. In 1811 the garrison at Placentia was withdrawn to St. John's, and not even the outbreak of war with the United States the next year caused the authorities to reverse this decision.

The war with the United States found Newfoundland exposed to the depredations of American privateers, often commanded by men familiar with Newfoundland waters. In 1813, the Americans captured about 20 Newfoundland fishing vessels. However, as in previous wars, the privateers were seeking more profitable prey than this. The Royal Navy responded by assigning more warships to the Newfoundland station, so that very quickly the hunters became the hunted. With the establishment of temporary batteries at several points on the east and south coasts and the adoption of close convoys, the American threat evaporated and the people of Newfoundland could return to the business of fishing.