The Karluk Disaster

In the summer of 1913, the wooden-hulled Karluk departed Canada for the western Arctic. On board were 10 scientists, 13 crewmembers, four Inuit hunters, one seamstress, her two children, and one passenger. Of these, 11 never returned and most were not heard from again until September 1914. During their 13-month exile, expedition members survived for seven months amid the drifting and inhospitable Arctic ice floes before establishing camp on an uninhabited island hundreds of miles north of Siberia.

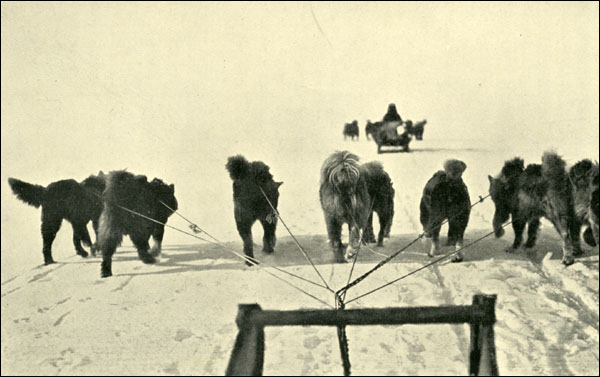

Many expedition members lacked any experience in Arctic travel and likely owed their lives to the knowledge and leadership skills of Karluk captain and polar explorer Bob Bartlett. Under his guidance, survivors built a camp on the ice, weathered the long Arctic night, and travelled 150 miles by dog sledge to find land. From there, Bartlett and one other team member completed a perilous 700-mile journey to the Bering Strait, where they searched for a vessel to save their stranded crewmates.

Canadian Arctic Expedition

After returning to Brigus from the 1913 spring seal hunt, Bartlett received a telegram from Canadian explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson asking him to captain the Karluk, flagship of the government-backed Canadian Arctic Expedition. The vessel's mission was to take a crew of geologists, anthropologists, meteorologists and other scientists north of the Yukon to Herschel Island, where they would establish a base and survey the region's flora, fauna, mineral deposits, and other characteristics. The party was also to search for any new land masses north of Alaska. It was the largest scientific expedition into the north to date and Ottawa hoped it would also help assert Canada's sovereignty over the Arctic islands.

Although Bartlett agreed to captain the Karluk, he was concerned about the vessel's ability to navigate through the dangerous Artcic waters. Instead of a new steel-hulled icebreaker, the government acquired for the expedition an old and underpowered wooden barkentine that had been converted into a whaling vessel in 1899. Workers reinforced the vessel with crossbeams and extra sheathing and Bartlett accepted the mission under an assumption that he would not spend the winter in Arctic waters.

The vessel departed British Columbia on 17 June 1913, but encountered heavy sea ice less than two months later. By 13 August, winds and the water's movement caused the ice to close in and freeze around the Karluk, which became solidly trapped about 225 miles northwest of Alaska. The vessel drifted helplessly with the pack ice, unable to free itself and reach Herschel Island.

The ice, however, stopped moving for a few days in mid-September and Stefansson decided to leave the ship with five other men, 14 dogs, and two sledges to hunt caribou. The group prepared for a 10-day expedition, hoping the ship's static position would allow them to return safely. Just two days after their departure on 20 September, strong winds moved the Karluk rapidly to the west, making it impossible for Stefansson and his team to find the vessel. Instead, they travelled south by dog sledge and eventually reached Alaska.

The Karluk, meanwhile, drifted for months amid the unpredictable Arctic floes until the ice punched a large hole its side on 10 January 1914. Fortunately, Bartlett had prepared for the sinking weeks earlier when he ordered crewmembers to build igloos on the ice and transfer to its surface most of the ship's food, fuel, and other supplies. As the Karluk slowly sank, expedition members removed all remaining supplies and then abandoned ship. Bartlett stayed onboard until the last possible moment, playing dozens of records on the ship's Victrola. At about 3:30 p.m. on 11 January, he placed Chopin's "Funeral March" on the turntable, stepped onto the ice, and watched the Karluk disappear below the water.

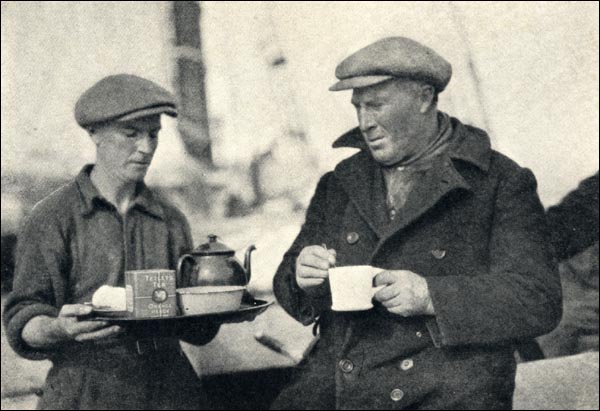

Shipwreck Camp

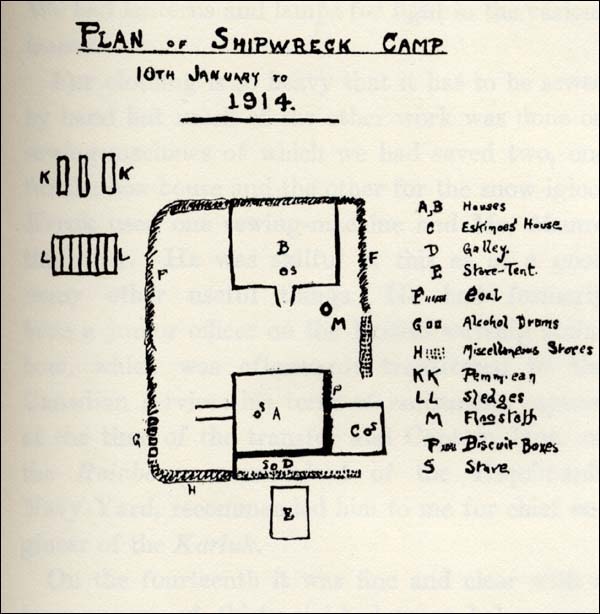

The Karluk sank during the middle of the Arctic night, which lasts from about mid-November until the end of January. Although Bartlett realized the expedition's best chance of survival was to find land, he did not want to take expedition members – many of whom had no experience in Arctic travel – across the ice in the dark. Fortunately, the expedition had enough food and fuel to live off for months; it also had several igloos to serve as shelter. Bartlett planned to remain at what he called Shipwreck Camp until the light returned in February, at which point he and all other expedition members would travel by dog sledge to Wrangel Island in the south.

Four men in the group, however, disagreed with Bartlett's plan and decided to travel south on their own. At their request, Bartlett equipped them with a sledge, dogs, and enough supplies to last 50 days. In return, the men wrote Bartlett a letter absolving him of any responsibility for their decision. The four left Shipwreck Camp in late January and were never heard from again.

In the meantime, Bartlett decided to send small teams of men across the ice to establish a chain of supply caches toward Wrangel Island. The first group, which consisted of the Karluk's first and second mates as well as two crewmen, departed on 20 January. Alongside stowing supplies, the men were also to look for Herald Island, which Bartlett believed lay about 50 miles south of Shipwreck Camp. Although the men eventually reached the island, they never left – likely because of running ice and open water. Other expedition members came searching for them about a week later, but falsely assumed they had fallen through the ice and died. It was not until 1929 that a passing vessel found their skeletons on the island.

Once the sunlight returned and supply caches had been established, Bartlett and all remaining expedition members left Shipwreck Camp on 19 February and began travelling by dog sledge to Wrangel Island. The group, which now numbered 17, took with it 12 dogs, three sledges, and enough supplies to last 60 days. Its members reached Wrangel Island on 12 March after travelling approximately 100 miles through the ice and cold.

Seven-Hundred-Mile Sledge Journey

Six days after arriving, Bartlett and one other expedition member, Inuit hunter Kataktovick, departed on a perilous 700-mile sledge journey to Siberia and then to the Bering Strait for help. Although Bartlett had originally planned to take all expedition members to Siberia, many were in a severely weakened condition and unable to make such a difficult and dangerous trip.

"From now on," wrote Bartlett in The Karluk's Last Voyage, "our journey became a never-ending series of struggles to get around or across lanes of open water – leads, as they are called – the most exasperating and treacherous of all Arctic travelling" (179).

In early April, the two men reached a small Inuit village in Siberia where residents gave them food, a bed, and helped mend their clothing and dog harnesses. Although Bartlett and Kataktovick had already crossed 200 miles in less than three weeks, they only stayed in the village for two nights before beginning the long journey to the Bering Strait. This time, they travelled across land, stopping at a few small villages along the way for food, rest, and sometimes to acquire a new sledge dog.

By the end of April, the two men reached East Cape (also known as Cape Dezhnev) on the Bering Strait, where Bartlett searched for a vessel that would take him to the closest wireless station at Alaska. Most ships, however, did not begin sailing from East Cape until late spring and it was not until 21 May that Bartlett departed aboard the Herman. He arrived at St. Michael, Alaska on 28 May and wired government officials in Ottawa of the Wrangel Island castaways. Bartlett also began searching for a vessel that would take him into the Arctic to rescue survivors, but he first had to recover from the severe swelling in his legs and feet that made it almost impossible for him to walk.

Rescue

Although Bartlett departed for Wrangel Island aboard the American vessel Bear on 13 July, it was the Canadian schooner King and Winge that rescued survivors from Wrangel Island on 7 September 1914 – almost eight months after the Karluk sank. Bartlett was reunited with his fellow survivors the following day, after the King and Winge encountered the Bear. Three men, however, died on the island and the remaining 12 expedition members survived by digging for roots and hunting duck, seals, walrus, and other animals.

"Mukpie - Point Barrow Eskimo Girl

Youngest Person aboard, and one of the

Survivors of the SS Karluk

Canadian Arctic (Stefansson) Expedition."

Although an admiralty commission later criticized Bartlett for agreeing to take the Karluk into the Arctic and allowing a group of four to travel south on their own, the press and public celebrated him as a hero. The Royal Geographic Society gave him an award for outstanding bravery and many survivors credited him with saving their lives, particularly William Laird McKinley, who later wrote: "there was for me only one real hero in the whole [Karluk] story – Bob Bartlett. Honest, fearless, reliable, loyal, everything a man should be" (Niven 366).