The Railway and Newfoundland Society

It was anticipated from the first that the railway would transform Newfoundland. The push to modernize, and the Victorian cult of progress were behind much of the late 19th century railway construction, railway politics, railway financing. Newfoundland had to be "ready" for the 20th century or it would be surely left behind the rest of the Empire and its North American neighbours.

So the railway was intended to make Newfoundland more like its neighbours and rivals. It was necessary to allow the "Oldest Colony" to compete in the modern world, and it was seen as central to economic development along more "normal" lines. Development of a mixed economy of land-based resource extraction and manufacturing would replace historic reliance on the quaint, rough-and-tumble cod fishery.

Assessment

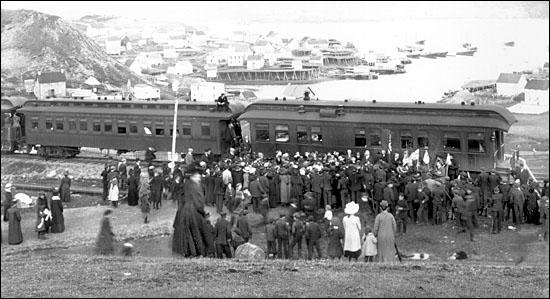

An initial assessment of the social impact of the railway ought to concentrate on the extent to which the anticipated benefits were realized. First, the construction and operation of a trans-insular railway was seen as an exercise in nation building. Having rejected Confederation with Canada in 1869, many Newfoundlanders saw the construction of a railway as a necessary next step. It cannot be denied that the railway did much to bring Newfoundlanders together. Railway construction crews and sectionmen were critical in spreading from east to west the family connections so crucial to the sense of a country. The railway (in conjunction with the coastal steamer service) helped to foster the sense of a country among Newfoundlanders, and was vital in spreading the reach of the colonial government to the west coast and the interior.

In terms of the settlement of the west coast of Newfoundland (the Humber Valley, Bay of Islands, Bay St. George and the Codroy Valley), the pioneering phase pre-dated the completion of the railway in 1898. While the railway can, for instance, be said to have opened up new markets for the farmers of the Codroy, the Valley had been recognized as the agricultural jewel of the Island many years. But the railway did open the eyes of many in the older commercial centres of the east to the potential of the west coast and "gave Newfoundland a West" on the model of its North American neighbours. Corner Brook, Channel-Port aux Basques and St. Georges became major population centres of the West Coast based in large part on their railway connections to the rest of the Island. It was also the construction of the railway that helped force a satisfactory conclusion to the French Shore issue.

The railway created a new region the central interior. Inland towns such as Whitbourne, Grand Falls, and Bishop's Falls were not the only creatures of the railway; head-of-bay rail and coastal steamer terminals rose to prominence. Modern-day "regional service centres" such as Clarenville and Lewisporte began as railway centres.

One of the priorities of those advocating a Newfoundland railway in the 1860s and 1870s has been largely forgotten: the imperative that Newfoundland "take its place" within the British Empire. This goal combined ambitions of social and economic modernity (to raise Newfoundland to the status where its contributions in imperial circles would be acknowledged and appreciated), with a conviction that an outward-looking Newfoundland should be a full participant in the continued march to glory that was the British Empire.

Hindsight

In hindsight, the motivation of the most persistent advocates of the Newfoundland railway was a conviction that Newfoundland must join the rest of North America. The first step was seen as building a railway and the second as developing the type of land-based resource extraction economy that would be served by a railway. The Antis of '69 won the day through reminding Newfoundlanders that they were turned face to Britain and back to the Gulf. But it was one of the defeated Confederate candidates in that election, William V. Whiteway, who formed a government '78 and whose "Policy of Progress" succeeded over the course of the next two decades in using the railway issue to marry Newfoundlanders' patriotism and ambition in wholehearted pursuit of the North American connection.

Consequently, in looking at the social impact of the railway on Newfoundland it is often difficult to separate the intended and the inevitable - those changes and trends which can be tied directly to the railway and those which were simply another badge of the march of progress.

Historians have yet to completely analyze the contributions of the railway in such trends as the development of the a wage-based economy, the mobility of labour, migration and settlement patterns within Newfoundland, popular culture, and the rise of unions and social movements. The question of how the railway and railway politics affected the fishery must be regarded as another avenue of enquiry that has spawned more questions than answers. Yet the consensus in all sectors is that the impact of the coming of the railway, while perhaps difficult to measure, is nonetheless profound.

But in exploring the impact of the railway on 20th century Newfoundland inevitably brings one to ponder the railway's impact on the central event of that century - Confederation in 1949. Did the railway really build Newfoundland into a country, as Sir William Whiteway had dreamed? Or did those opposed to Whiteway who had denounced the railway as a back-door confederate plot see their worst fears answered?