Agriculture

Newfoundland and Labrador's climate and soil have not been conducive to agriculture, but outport isolation and poor incomes in the fishery have made supplementary farming crucial. Fishing families raised root crops, some hay and oats, and livestock for their own use, but traded marginal surpluses locally. In the early part of the nineteenth century, severe potato blight combined with bad weather and failures in the fishery, forced the government to provide poor relief to prevent famine.

Exasperated with poor relief, the colonial government embraced commercial agriculture by the 1840s, believing that the colony had great interior agricultural resources. Many of Newfoundland's first roads were the result of able-bodied relief programmes designed to look for such resources. Pockets of good land were occasionally found and farmed, but without lessening overall dependence on the fishery for employment. Persistent poor fish catches throughout the 1860s led government to pass new Crown Lands legislation that facilitated land grants and clearing for agricultural purposes. When catches improved from 1869 to 1874, government did little to cultivate agriculture further, but a bad fishery in 1875 led to a renewed policy commitment to farming.

Commercial Farming

Early commercial farming was most successful close to St. John's, which, as the colonial capital and military centre, provided a good local market for farmers. Farming concentrated in the Waterford and Freshwater Valleys, as well as in Kilbride, the Goulds, Logy Bay, Outer Cove, Middle Cove and Torbay. Military officers and professionals invested in country estates to be considered respectable. Sir James Pearl's farm to the west of St. John's, "Mount Pearl," was one such estate. More typical were the smaller farms built by labourers such as William Ruby in the Goulds. Through the 1850s and 1860s Ruby's thriving farm supplied the St. John's market with vegetables, hay and livestock products. Over time, farmers close to St. John's began to specialize in the production of fresh milk, eggs, and meat for the local market.

Commercial farming otherwise faced enduring problems. There were few local markets, and marine transport facilitated the import of cheaper farm goods. Local farms generated little employment relative to the massive government funding spent to encourage them. Between 1886 and 1898 governments succeeded best in encouraging supplementary rather than commercial farming independent of the fishery.

From 1891 to 1921 the increasing populations of the outports had cultivated almost every bit of available arable land. The development of employment in pulp-and-paper and mining towns alleviated some of the pressure on the relatively poor farm land of coastal areas. These towns also provided good local markets for the agricultural products of newer farming and fishing settlements such as Musgravetown along the northeast coast, and the communities of the Codroy Valley on the west coast. In 1919, the government established a model farm to build on these new developments. With the Great Depression, expansion of employment in the mining and forestry sectors came to a halt, and many outport people could no longer find work abroad in Canada and the United States. Many returned to the outports even as fish prices plummeted, and local markets for outport farm products proved limited.

Agricultural Land Settlement

The Commission of Government tried to solve unemployment through agricultural land settlement during the Great Depression. A Demonstration Farm and adjunct Agricultural School were established between 1935 and 1936. Unable to afford agricultural education programmes for the outports, the Commission favoured centralized commercial farming communities, and sponsored the construction of Markland, Haricot, Lourdes, Midland, Brown's Arm, Sandringham, Winterland, and Point au Mal.

The residents were supposed to live and farm cooperatively, but the land settlement schemes failed. Much of the Commission's effort went into trying to eliminate denominationalism and to reform the character of settlers rather than into making agriculture work. Most of the potential farmers in these settlements became discontented, and returned to the war-rejuvenated fishery, logging, or entered new employment on military bases by 1944-45. The Commission eventually accepted that most rural Newfoundlanders lived in areas that were not suitable for commercial farming, and began to support supplementary farming by fishing people.

Supplementary Farming

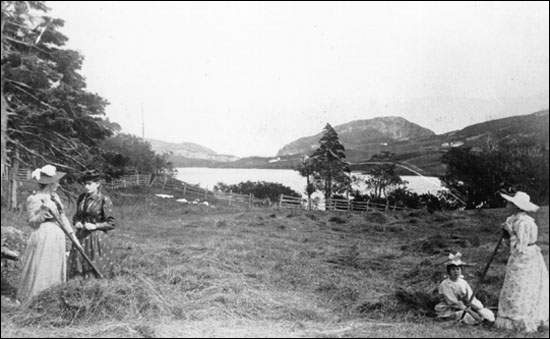

Supplementary farming was socially and culturally important. While men worked in the fishery, women did most of the planting and fertilizing, and took great pride in keeping their potato gardens weed-free, or in the quality of their hay-making. Few outport women wasted their meagre land on ornamental flower gardening. Those who cultivated more than vegetable and hay crops grew flowers and herbs which had medicinal or seasoning uses, or raised small fruits such as black currants. While fishing dictated that settlements were scattered along the rugged coastline, gardens were as important as flakes, stages and slips. Lanes snaked around communities to avoid spoiling good gardens. People had vegetable gardens instead of lawns, and used unique stick fences to keep animals out. Larger vegetable and hay gardens surrounded most outports.

Modernization and Industrial Development

Farming and fishing were hard work, and did not prevent poverty. The experience of the Great Depression, and the more prosperous times of World War II meant that many rural people accepted J.R. Smallwood's promises about Confederation: new prosperity through transfer payments and industrial diversification. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s Smallwood improved living standards by expanding the social welfare system. But his industrial diversification schemes failed to reduce rural dependence on the traditional outport economy.

Newfoundland's agricultural policy assumed that industrialization would succeed. A 1953 provincial royal commission recommended that the government discourage supplementary farming in favour of larger, more concentrated commercial farms, claiming the former produced little value. Inshore fishing communities were expected to disappear as the fishery modernized, industrialized, and centralized in a few larger communities. Supplementary farming would vanish with the outports.

Despite resettlement in the 1960s and 1970s, Newfoundland remained dependent on the modernized and inshore fisheries. Integration into Canadian markets made imported food even cheaper, and welfare and social security payments provided outport residents additional means to buy it. However, promised incomes from industrial diversification failed to materialize, and many rural Newfoundlanders nevertheless continued supplementary farming, although on a reduced scale.

Although the low cost of outport farming, due to family labour and local natural fertilizers, impressed observers in the Canadian agriculture press, the provincial government limited its support of agriculture to the commercial production of poultry, pork and dairy products, as well as mink farming. The government fostered larger ventures because it wanted to stabilize centralized agricultural production that could be more easily regulated, and supposedly would be more economical, but large-scale commercial farms proved cost-effective only by mechanization that eliminated employment.

The poultry, dairy, and meat sectors came to depend on government subsidies and industry-controlled price support boards. Such supports particularly stabilized fresh milk supplies, but at the expense of increased costs to consumers. The Newfoundland government facilitated the grading and processing of meat at facilities owned and operated by a provincial Crown Corporation first established in 1963: the Newfoundland Farm Products Corporation.

Encouraging Agricultural Development

Throughout the 1970s governments encouraged agricultural development primarily in designated development areas such as the commercial dairy region of Musgravetown-Lethbridge in Bonavista Bay. In the late 1980s, the government supported the introduction of new agricultural technology in the form of the Sprung hydroponics facility in Mount Pearl. Hydroponics on such a large scale proved too costly, and the Sprung enterprise closed in 1990, although smaller-scale hydroponic operations persist.

The provincial government continued to support commercial agricultural development in production and processing in the 1990s. The focus was on the development of agriculture as a business marked by mechanization, and organized within a free-market environment. This meant the elimination of much of the subsidy which had made full-time commercial production possible. Although supplementary farming had remained important to provincial agriculture, it now received little state support.