Down North on the Labrador Circuit:

The Court of Civil Jurisdiction 1826 to 1833

by Nina Jane Goudie

The Legal System in Labrador

The realities of running a court in Labrador are reflected in the Rules of Practice and Proceedings. For example, there may have been a tendency for litigants to take advantage of their remote location by executing a false writ because Rule No. 6 instructed the Judge to carefully consider cases where the principal evidence in the case was known by only one of the parties concerned. The instructions noted that,

... the person who gives evidence under such circumstances may be placed under a strong temptation to causing perjury, the Court ought to be very cautious in allowing a party to become a witness in his own causes... and... it ought to require the party ... to pro-duce two or three credible witnesses...75

Another example was Rule No. 7 which cautioned the Judge about issuing a judgment by default.76 When such a judgment was issued, if the “party against whom a judgment by default shall have been given will come into Court before expiration of the second day,” the Judge was to set aside the earlier judgment and hear the case. Another feature unique to Labrador was Rule No. 9. It cautioned against sentencing anyone to imprisonment because there were no jail facilities in Labrador. Instead, Judge Paterson was advised to either issue a Writ of Execution (Form No. 5) or refer the case to the Supreme Court.77

As Tucker adapted the General Rules and Orders of the Circuit Court to apply to Labrador, judge Paterson, in turn, adapted the rules liberally in the interests of a quick but fair conclusion to a dispute. A clear example of this related to Rule No. 5. The Court could not hear a civil case if its value exceeded £50, or,

where the matter in dispute shall relate to the title of any lands, tenements, rights of fishery, annual rent or other matter where in the judgment of the Court, rights in future may be bound...78

In these cases, the Clerk of the Court was to forward details to the Supreme Court in St. John's. Between 1826 and 1833, seventeen or about 14% of the total number of cases were above the £50 cutoff. Only one was referred to the Supreme Court; the rest were resolved through settlement outside of Court, mutually settled in Court, or withdrawn. The wish to resolve disputes amicably is demonstrated by a high degree of compromise by the parties. Judge Paterson often filled the role of arbitrator and in some cases the parties agreed to have the cases decided by “disinterested persons.” 79 Sullivan v Hoar was the one case referred to the Supreme Court because it involved title to land. Three years previously Sullivan had built a fishing room and stage in Indian Tickle. Hoar fished the area for years and had recently trespassed on Sullivan's land, indicating he intended to lay claim to it.80 By the time the case came to court Sullivan and Hoar had settled. However, Sullivan asked Judge Paterson to present a case to the Supreme Court for title to the land in question. After viewing the property, Paterson agreed, indicating that his “report to His Excellency the Governor of his [Sullivan's] case would be favourable to his wishes.” The extent to which the recognition of private property provided through the Registrar of Deeds extended to Labrador, and Cochrane's response to Paterson's report is unknown. Given that Newfoundland's jurisdiction in Labrador remained tenuous and that Newfoundland wished to avoid cases in which “rights in future may be bound,” Sullivan's request might have been denied.81 But we do not know. 79 Sullivan v Hoar was the one case referred to the Supreme Court because it involved title to land. Three years previously Sullivan had built a fishing room and stage in Indian Tickle. Hoar fished the area for years and had recently trespassed on Sullivan's land, indicating he intended to lay claim to it.80 By the time the case came to court Sullivan and Hoar had settled. However, Sullivan asked Judge Paterson to present a case to the Supreme Court for title to the land in question. After viewing the property, Paterson agreed, indicating that his “report to His Excellency the Governor of his [Sullivan's] case would be favourable to his wishes.” The extent to which the recognition of private property provided through the Registrar of Deeds extended to Labrador, and Cochrane's response to Paterson's report is unknown. Given that Newfoundland's jurisdiction in Labrador remained tenuous and that Newfoundland wished to avoid cases in which “rights in future may be bound,” Sullivan's request might have been denied.81 But we do not know.

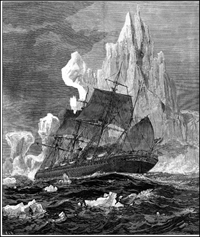

Iceberg

"An Encounter with Icebergs" by Schell and Hogan, ca. 1880.

From Charles de Volpi, Newfoundland: a Pictorial Record (Sherbrooke, Quebec: Longman Canada Limited, ©1972) 157.

with more information (324 kb). with more information (324 kb).

|

|

|