|

A Cautious Beginning: The Court of Civil Jurisdiction 1791 by Christopher English and Christopher Curran The Centrality of Law in an Emerging Civil Society The late 18th century marked a watershed in Newfoundland's legal development. To this point it is unclear what factors contributed most forcefully. Clearly there was no intent to dismantle the statutory regime which regulated the fishery as an imperial interest. The population was increasing, to roughly 17,000 in 1793, and Hutchings' success in 1787 had rendered ultra vires the jurisdiction of the Sessional Courts which ministered to the local populace when the fishing admirals were non-resident. As in the 1770's with regard to the Thirteen Colonies, so in the 1790's with regard to France, England was battening down the hatches in face of the threat of war, a reality from 1793.

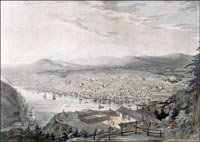

If Britain was not actually retreating from Empire, she seemed inclined to put her colonial affairs in statutory order. From an imperial perspective the Act of 1791 may have complemented the Constitution Act of 1791 which established Upper and Lower Canada. Finally, it is clear that changes in the fishery mandated reform. Largely unnoticed, the fishery from mid-century had been internally transformed from a migratory and seasonal to a settled and year-round enterprise. The Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars contributed to this process and brought such an era of prosperity that despite the post- 1815 economic slump there could be no going back. Exports of fish grew to 400,000 quintals in 1800, 800,000 in 1810, and a million in 1815, by which time the population, fuelled by Irish immigration after 1798 and by Europe's demand for fish, had increased to 38,000. Fifteen thousand immigrants arrived in the two seasons of 1814-15. Ten years later the population stood at 55,000. Settlement expanded beyond its historic centres on the Avalon Peninsula and in Conception and Trinity Bays to Placentia and Fortune Bays on the south coast. By 1810 over 1000 sea-going ships were resident. In 1814 a common fisherman could make a seasonal wage of the previously undreamt of order of £70. Seals from 1794 offered a supplementary source of income, 40,000 being taken by ships from Conception Bay in that year. By 1904, 160,000 pelts were being exported, with 1500 men in 150 vessels sailing annually to the Front off Labrador. Logging and ship-building offered the prospect of helping to sustain the population in a year-round economy.44 By War's end it appeared that the critical mass of population necessary to sustain permanent settlement had been surpassed. Wartime governors capitulated to popular demand and the crying need for food by making available 80 acres on the "higher levels" above St. John's for agriculture.45 The first municipal institutions were in place: two schools in 1804, a postal service in 1805, a newspaper, the Royal Gazette, in 1806, which had been joined by three more by 1820, philanthropic societies (a Society for the Improvement of the Poor in St. John's in 1803 and the Benevolent Irish Society in 1806), and a hospital in 1811. The first part-time special pleaders who would provide the nucleus of the Bar of the Supreme Court in 1826 had appeared, and before 1815 at least two trained lawyers, James Simms and William Dawe,46 were in practice.

Newfoundlanders, for as such they were beginning to see themselves, were still precariously situated and a long way from being maîtres chez eux. The peace of 1815 reaffirmed French treaty rights. In 1818 an Anglo American convention permitted American fishing from Ramea on the south coast west and north to the tip of the Northern Peninsula, along the coast of Labrador and through the Gulf to the Magdalene Islands. The continuing and consistent refusal of Britain to help fund the local administration was a severe disability. But after 1815 it was accepted in St. John's and at Westminster that Newfoundland was de facto a colony. She had achieved the requisite critical mass of population to emerge as a distinct entity. The temporary judicial arrangements of 1791 and 1792, made permanent in 1809, laid the basis for the assumption of legal personality as a colony in 1824, and paved the way for representative government in 1832.47 Settlement demanded governance and the putting in place of institutional structures. In that process the leadership assumed by the legal community would be significant, for the law, embracing institutions, personnel, substance, process and ideology, was in place. The product of statute, prerogative writ and customary practice over three centuries, it was, as far as one can tell, popularly supported. In the generation after 1815, when so much in the basic structure and institutions of politics, the economy, education, health and municipal government had to be decided, the law, legal culture and the legal community offered a context and a means for reform. The law, its values, and its practitioners who would rapidly emerge, stood ready to assume a leadership role. Indeed it appears to have been theirs for the taking. |

||||||||

|

||||||||