Carson and Morris

William Carson and Patrick Morris were by far the two most important leaders of the reform movement in Newfoundland. Together they dominated the campaign to replace the system of naval government and surrogate courts with a civil governorship, a reformed judiciary, and a legislative assembly. Although their roles have at times been exaggerated-some writers have claimed that Carson single-handedly won the grant of representative government-their speeches, pamphlets, and tireless lobbying were absolutely essential to the eventual success of the reform movement.

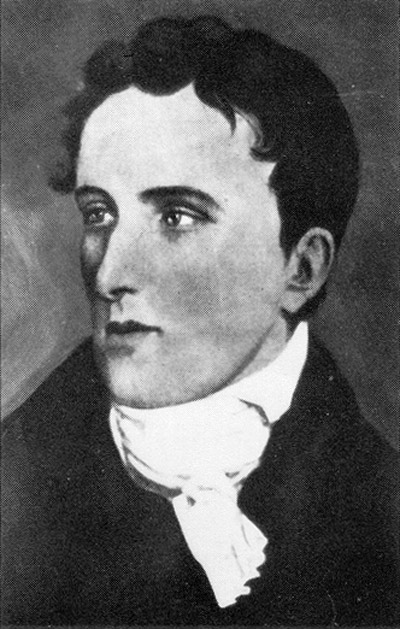

Neither Carson nor Morris was born in Newfoundland. Like most of the other St. John's reformers, they were part of the large wave of immigrants from Britain and Ireland in the early 19th century. William Carson was a physician who emigrated from Scotland in 1808, while Patrick Morris arrived from Ireland in 1804 and entered the mercantile trade.

Historical studies of Carson and Morris have focused largely on their personalities and political rhetoric. According to Judge Prowse, they were very different public figures: whereas Carson was a stiff, pedantic and independent Scotsman, whose writings exhibited calm reasoning, Morris was an impetuous Irishman who relied on his great passion and wit to build popular support. Their vigorous critiques of mercantile power and their efforts to foster agricultural development have received the lion's share of scholarly attention, but Carson and Morris both placed law and justice at the centre of their political philosophy. While they employed distinct rhetorical styles, they shared a common intellectual view of the role of law in building a viable colonial society.

In assessing Newfoundland's problems, Carson and Morris adopted a similar three-stage logic. First, they recounted the island's long history of oppression under the tyrannical rule of fishing admirals and naval governors. In doing so, they not only drew on previous writers, such as Chief Justice John Reeves, but they also crafted their own version of Newfoundland history. Like most other nationalist movements, the St. John's reformers moulded a historical memory as a basis on which to mount attacks on the status quo.

For example, Carson asserted with biting sarcasm that the island's legal problems stretched back to its earliest settlers:

The inhabitants appear to have been considered, either as a race of savages untameable by civilization, and which could not be re-trained by any regular code of laws, or as Angels descended immediately from Heaven, pure and perfect, possessing minds which did not require instruction, and passion that needed not the control of terrestrious [sic] institutions (Carson 1813 5).

And, in a lengthy speech devoted largely to Newfoundland history, Morris offered a similarly harsh appraisal:

Here, Gentlemen, a system of Government was established for this country unequalled in the annals of the most despotic nations, and a system better calculated to oppress and barbarize a country, was never framed by the perverted ingenuity of man. Under this authority the most wanton acts of violence were committed-the houses and property of the Inhabitants and Planters were burnt and destroyed, and every other means were resorted to, to drive them from the land of their birth, or their extirprate [sic] them altogether. It is scarcely creditable at the period we live in, that such a state of things could exist in a country calling itself civilized. (Anon. 1821 43-44).

In essence, Newfoundland under naval government had failed the test of civilized society.

The second plank in the platform for law reform was the comparative argument of the rights of Newfoundlanders versus those of other British subjects. Carson maintained that those living in Newfoundland had, by virtue of their birthright as British subjects, an unfettered claim to the full rights accorded to all Britons. Morris pointed out that the English and Irish settlers were, in fact, "all descended from the free born subjects of Britain, who carried with them all their rights and privileges as British subjects, which neither they nor their subjects forfeited." (Morris 1828 39). "The only remedy against the evils flowing from the present system," Carson concluded, "will be found in giving to the people, what they most ardently wish, and what is unquestionably their right, a civil Government, consisting of a resident Governor, a Senate House, and a House of Assembly" (Carson 1813 12-13). Both Morris and Carson pointed out that other colonists in British North America had long enjoyed civil rights denied those living in Newfoundland.

The third element of the reformers' logic focused on the socio-economic impact of Newfoundland's legal system. Carson and Morris, like many of their contemporaries, believed that the laws governing Newfoundland had retarded its development. They saw legal rights and economic growth as inexorably linked together. The premise that King William's Act restricted settlement-a mistaken supposition that persists to the present day-figured prominently in the writings of both Carson and Morris. Carson noted:

In the preamble to Act 10 and 11 of William III the commercial advantages of this Island, and its consequence as a nursery for seamen, appear, by the English Legislature, to have been fully known and appreciated. The subsequent laws, and the general policy of its every changing Governors, have not been calculated to enlarge its consequence, or promote its interests. The people have obtained but little increase in their civil rights. Population has been checked by restraining laws: by the prevention of agriculture the necessaries of life have at all times been dear; and sometimes difficult to procure (Carson 1813 6).

Though he employed more dramatic rhetoric, Morris made essentially the same point in a public speech:

If, Gentlemen, you are convinced that the statement I have made of the laws by which Newfoundland has been governed is faithful, you cannot be surprised at the present state of the country. The most luxuriant country in the world, situated in the most temperate climate, under such laws would become an uninhabitable wilderness. Governed by such laws, even England would be now in a worse situation than it was at the invasion of Julius Caesar; that country, which is now the boast of every Briton, and the wonder of an admiring world, would most probably at this day be farmed out to a company of Jews, and its inhabitants only employed in extracting coal and tin from its mines (Anon. 1821 50. Emphasis added).

This type of legal determinism was far from unique to St. John's politics-reformers throughout British North America were using such language in the early nineteenth century-but its persistence in modern studies of the law only serves to perpetuate one of the core myths of Newfoundland nationalism. It is important, therefore, to examine the philosophy of Carson and Morris not only to trace the course of law reform, but also to confront some of the misconceptions that still cloud Newfoundland history.